The Ballparks

County Stadium

Milwaukee, Wisconsin

It was a plain stadium with a plain name, but the folks who paid for County Stadium provided the personality with brats, brew and a healthy dose of Gemuetlichkeit, bringing true Happy Days to Milwaukee by shattering 50 years of major league entrenchment and sparking a volatile period of geographical readjustment within the game.

When County Stadium sat empty, relaxed in the Menomonee River Valley two miles west of downtown Milwaukee, there was an unremarkable nature about it. If you were looking for a wow factor, you weren’t going to find it amid the ordinary double-deck structure, the symmetrical playing field, the sea of parking spaces that surrounded it or the boxy facade with the stadium name spelled out in industrial lettering.

What was remarkable about County Stadium was the unique context within which it was built, the unprecedented enthusiasm from the fans who welcomed it, and the geopolitical influence it would set for baseball throughout the second half of the 20th Century.

When the construction dust was blown off of County Stadium in the winter of 1953, the same 16 major league teams had cemented themselves in the same 10 markets for the previous 51 years. There had been no expansions, no relocations. Given this inflexible state of affairs, no other city had ever dared to build it with the hope that they would come. Until, that was, Milwaukee, a city which had been given four previous shots at the major league level—none of which lasted more than a year—and was the last to watch a team pack and up and leave town in favor of another when the 1901 Brewers, a charter American League franchise, left for St. Louis and become the Browns.

Milwaukee would eventually get even.

When the Cream City built County Stadium, they came. And the business of baseball would never be the same—as Milwaukee would discover over the facility’s lifespan in both the best and worst of ways.

Much of Milwaukee’s baseball prologue to County Stadium would be written with a minor league accent. That’s in large part because the city was weighed down by a decaying ballpark in Borchert Field, an aging, 14,000-seat facility forged into a rectangular city block with rotten sightlines and a rickety reputation—one that was horrifyingly confirmed during a 1944 game when a fierce gust of wind blew off a chunk of the roof, injuring 30 fans and causing damage to nearby homes. But in its dying years, Borchert Field served as the home for the minors’ hottest team of the 1940s as promotional wizard Bill Veeck bought the American Association version of the Brewers and employed the savvy level of marketing chutzpah that would define his future ownership of major league teams. It showed not only that Veeck could run a team, but also that Milwaukee could support baseball at a major league level—if only it had something to replace fragile Borchert.

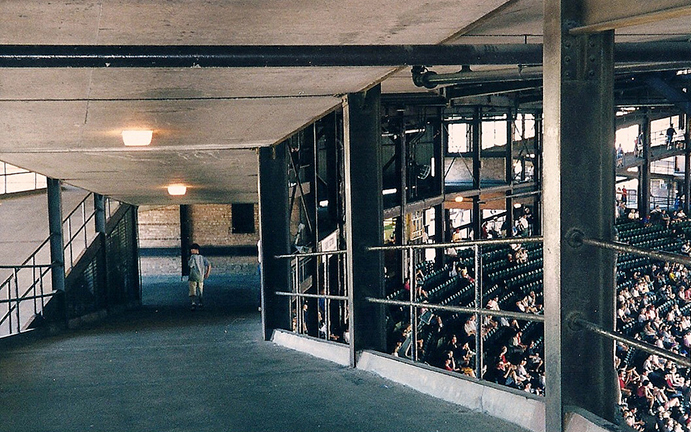

Spectator ramps and catwalks dominated behind the scenes at County Stadium. Escalators need not apply—for better or for worse. (Flickr—Cragin Spring)

A Centennial Gift.

In 1946, after years of chatter on the subject, the wheels began spinning for such a replacement. The 1948 Corporation, a consortium of Milwaukee’s finest from the political and business arenas, set an aim to reinvent the city to help celebrate the 100th anniversary of Wisconsin’s statehood. Included in this ambitious plot of public works was a new zoo, library, museum and a ballpark.

The 1948 Corporation had a huge fan in Lou Perini. Not only was he the owner of the Boston Braves, but he’d also recently bought out Veeck and took control of the Brewers as his top minor league affiliate. Many eyed Perini as one happy that a new ballpark could be built for his Brewers, but little did they realize his emerging long-term agenda—even after he dropped a hint of things to come by telling the Milwaukee Athletic Club: “Milwaukee will be in a major league within five years and should get ready for it.”

Milwaukee did. It got public approval to build County Stadium and, after choosing the site of a former stone quarry over the Wisconsin State Fairgrounds because of its closer proximity to downtown, construction commenced in October 1950.

At nearby National Soldiers Home Veterans Administration Hospital, bleacher-like benches were put up for patients and staff to watch the Braves; expansion in the late 1970s blocked the view.

Budgeted at $5 million, County Stadium would be the first major league facility to be built entirely with public funds. As such, there would be little glitz to spare at the new ballpark; Osborn Engineering, the veteran Cleveland-based firm picked as the project architect, was wisely sensitive to the almighty tax dollar and knew it didn’t have carte blanche do go palatial as it had done with some of the privately-built facilities on its portfolio such as Fenway Park, Yankee Stadium and Comiskey Park. So it stuck to the basics, designing a clean, no-frills ballpark with good views, spacious concourses (for the times) and manageable spectator access in and out of the venue.

Officially, the ballpark was being built for the Brewers—but that didn’t stop city officials from sending out glossy brochures to major league teams showcasing what a wonderful place Milwaukee was. Tourism was obviously not its goal, and baseball knew it; a year before County Stadium’s completion, owners had voted to loosen restrictions on franchise relocation. Rapidly, the question became less of whether the majors would come to Milwaukee, and more of which team it would be.

The Race For Wisconsin.

Most of the Milwaukee-bound buzz generated around Bill Veeck. After striking gold on and off the field with the Cleveland Indians in the late 1940s, baseball’s master showman wasn’t making it with his latest challenge: Turning a perennial laughingstock in the St. Louis Browns into a contender. Under his ownership, the Browns were still awful, and his bag of promotional tricks—which most memorably included a one-time appearance at the plate by 3’7” Eddie Gaedel—only seemed to enhance the team’s reputation as a clown act. Unless the Yankees were visiting or fans saw the Browns as morbid curiosity, nobody was going to watch this team so long as the more respectable Cardinals and their matinee idol Stan Musial also held court at Sportsman’s Park.

Veeck wanted to come back to Milwaukee and restore the Browns’ franchise to its original home. But Lou Perini got in the way.

The Braves’ owner could relate to Veeck. In 1948, Perini’s team had won a National League pennant (losing the World Series to Veeck’s Indians) and drew 1.5 million fans at home. But the team’s performance declined over the next three years and, more alarmingly, attendance crashed—all the way to a scant 281,000 in 1952. That figure led to losses of roughly $700,000; Perini, like Veeck, bemoaned the idea of hanging out in a berg dominated by a more popular team (the Red Sox) and its superstar (Ted Williams).

Perini was also eyeing Milwaukee for the Braves. But he held the ace card: His ownership of the minor league Brewers gave him territorial rights to the area.

As spring training commenced in 1953, Veeck announced to his fellow owners his desire to move the Browns to Milwaukee. Ecstatic over what little was leaking out of the boardroom, a Milwaukee business committee offered $500,000 to Perini to move the Brewers out of town and allow the Browns to move in. Perini said no to the group, and major league owners—who never liked Veeck for his outlandish, unorthodox marketing practices—said no to Veeck via a vote. Perini apparently had lobbied the Lords against the move so he could quietly make his own.

A week later, a new vote came up. It was unanimous: The Braves were headed to Milwaukee.

Christmas in April.

As the finishing touches were placed upon County Stadium—a year later than expected, owing to a shortage of available steel during the Korean War—news of the move hit the citizenry of Milwaukee like a thunderbolt of bliss. It became Christmas in April. In one Milwaukee hotel, literally; it placed a tree in the lobby to celebrate the birth of the Milwaukee Braves. The Brewers, meanwhile, became property of Toledo, and the Browns remained in St. Louis—but only for another year before moving on, without Veeck, to Baltimore.

Chilly, breezy, sometimes drizzly conditions didn’t keep 34,357 fans from jamming into County Stadium for the Braves’ first game on April 14, 1953. The fans were so excited at the moment, they sometimes went nuts over a simple pop foul. The Braves would keep them happy to the end as rookie Bill Bruton—who played in Milwaukee the year before for the Triple-A Brewers—tripled and struck a walk-off home run in the 10th to beat the visiting Cardinals, 3-2. Warren Spahn, as he was apt to do when needed, sailed past the ninth and went overtime to earn the victory.

After just 13 home games, the 1953 Braves had already surpassed the total gate of the 1952 Boston team. Realists within baseball saw Milwaukee’s early hysteria for baseball as a novelty that would quickly wear off, but they were badly proven wrong. The fans kept coming, and coming, and coming. By season’s end, the Braves would draw a NL-record 1,826,397 fans—more than double the total of every other NL team except Brooklyn, a distant second at 1.1 million. A year later, Milwaukee became the first NL team to eclipse the two million mark; it held steady at that figure until peaking in 1957 with 2.2 million. While other teams struggled to draw a million fans for an entire season, the Braves on occasion had advance sales of over a million before Opening Day. Gemuetlichkeit, a German term known by most Milwaukeeans as “cheerful times,” was in high gear.

Playing in Milwaukee meant a free ride for many Braves players. They rarely paid a cent for food, gas and clothing. The locals simply wouldn’t let them pick up the tab. When 20-year-old Hank Aaron arrived in Milwaukee in 1954 after enduring the racial hatred of the South, he was taken back by the graciousness afforded him from the city folk—black and white. He could have easily been treated to a shake paid for by Richie, Potsie and Ralph Malph.

The fans at County Stadium weren’t just passionate—they were nuts. Visiting players described the ballpark as an insane asylum with bases. One Milwaukee woman going through a divorce told a judge she wanted to break up because her husband refused to buy Braves season tickets.

The electricity generated by the large County Stadium crowds sent a powerful jolt into the Braves’ performance. They went from seventh place to second in their first year at Milwaukee and afterward were always in the pennant conversation, as future Hall of Famers Aaron, Spahn and slugger Eddie Mathews provided their own juice to keep the energy flowing. The wattage hit peak in 1957 when the Braves won their first of two straight Milwaukee pennants—and the city’s lone world title when they bested the mighty Yankees in seven games.

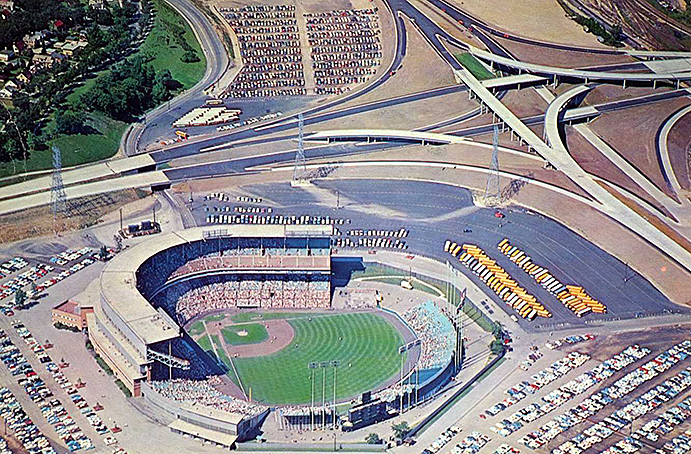

There was plenty of parking at County Stadium; the problem was getting there. That was remedied in the early 1960s with the completion of two intersecting freeways as shown here. (LL Cook and Co.)

Initially, County Stadium consisted of a petite, 28,000-seat double-deck structure that wrapped the field from third base to halfway down the right-field line. Seven thousand bleacher seats were set down beyond third base, behind left field and around the right-field corner to fill out the rest of the capacity. But the runaway success of the Braves’ inaugural season in Milwaukee made it clear that they were going to need a bigger ballpark. The city wasted little time, spending $1.5 million to extend the main structure further down the left-field line, extending the lower section around the right-field corner and creating permanent bleachers that stretched behind the fence from pole to pole. The revised capacity of 44,000 didn’t include a block of bleachers situated on a hillside not far behind the right-field corner, at the doorstep of the National Soldiers Home Veterans Administration Hospital—where patients and staff could easily view the game for free.

Everything about County Stadium wasn’t quite perfect. Someone forgot to install a hitter’s backdrop behind the center field fence, leaving batters with the difficult task of picking out a baseball from a sea of parked cars in the lots beyond. The Braves’ front office thought it would solve the problem by planting a grove of fir trees, but they never consulted the hitters; it ultimately wasn’t their ideal solution. Nicknamed Perini’s Woods, the trees eventually gave way to a section of darkened, closed-off bleachers in later years.

Parking also presented a problem. There were plenty of spaces around County Stadium to park the car, but getting there was a challenge in the early years. The introduction of two freeways and wider roadways into the ballpark lots eventually eased the issue.

Once the Braves conquered the World Series in 1957, ennui set it. The fans, once so impassioned with the mere thought of big league baseball in their city, started to show more complacency as the Braves spoiled them with one winning season after another. Attendance dropped at an accelerated rate through the next five years. Lou Perini was able to coast profitably through the Braves’ first five years in Milwaukee because the game sold itself; but outside the lines, he did nothing to maintain the enthusiasm. He held off on public relations, and fatally said no to Braves games on local TV—home or away—because he feared fans would become “saturated with baseball” and be less inclined to show up in person at County Stadium.

The honeymoon was over; the marriage would soon follow.

Georgia on Their Minds.

In 1961, the Braves lost money for the first time since moving to Milwaukee. A year later, they drew only 766,000 fans, their first sub-million gate. Worse for Perini, it was reported that he owed the IRS $1.5 million in back taxes. So at the end of 1962, he sold. It was first thought that the new ownership—a consortium of investors from nearby Chicago—would pump new energy into the franchise. But it saw in Milwaukee limited TV revenue potential and began to look elsewhere.

Elsewhere would become Atlanta. It was a larger market with a new stadium being built—and it held the promise of increased TV revenue. The Braves clandestinely began negotiations with Atlanta, but rumor spread anyway—and when Atlanta officials publicly teased in 1964 that they had been given an oral commitment from a major league team to move to their city in 1965, everyone in Milwaukee did a figurative glare toward the Braves and Bill Bartholomay, the team’s new big cheese who rarely came to County Stadium and evaded the press when he did happen to show. Relations between Milwaukee and the Braves hit an all-time low; local politicos accused Braves management and coaches of scuttling the season in order to keep enthusiasm low and ease any exit out of town. Gemuetlichkeit was kaput.

When the Braves finally came clean and announced their intention to move to the Deep South, Milwaukee sued—demanding that the Braves fulfill the obligations of the existing County Stadium lease and stay put through 1965. A judge agreed. What would become the Braves’ final season in Milwaukee was a surreal one, with a lame duck team playing in Wisconsin against its wishes in front of a jilted fan base. The team that once drew 20,000 fans without effort now witnessed gatherings that sometimes fell below 1,000, all despite the presence of a star-studded squad that was delivering Milwaukee with its 13th winning record in 13 seasons.

The court battle between Milwaukee and the Braves continued up the judicial ladder to the Wisconsin Supreme Court—which ruled 4-3 in favor of the Braves. (The U.S. Supreme Court refused Milwaukee’s appeal.) Milwaukee now knew how it felt to be Boston; County Stadium, which just a decade earlier was the place to be, was now without a baseball team.

County Stadium from the outside, featuring a near-modern mix of brick, limestone and sheet metal; from this view, one might initially mistook it for a large indoor arena. (Jerry Reuss)

The Milwaukee White Sox?

In the Braves’ absence, County Stadium was hardly a ghost town; it retained a part-time tenant in football’s Green Bay Packers in the midst of their legendary run under coach Vince Lombardi—the high point in a 42-year stay at County in which the Pack played anywhere from two to four games a season. Meanwhile, the city aggressively looked to bring baseball back. A civic group named after the old minor league Brewers and headed by young Bud Selig, auto dealer and devout baseball fan, convinced the Chicago White Sox and Minnesota Twins to play a 1967 midseason exhibition at County Stadium. The so-called experts, believing that Milwaukee fans still harbored genuine fury toward the majors, expected a modest gathering of 20,000; instead, 51,000 packed the joint to the point that officials employed the deadball era practice of placing an overload of fans on the field and roping them off from the action. The fire marshal said no to 5,000 other fans who couldn’t get in. A postgame fireworks display sweetened the bait, but the game clearly was the attraction for those looking to wash away the misery of the Braves’ departure and simply watch baseball.

Impressed by the turnout, the White Sox decided to let County Stadium host nine regular season games in 1968 and 11 more in 1969. They were impressed anew; Milwaukee’s average crowd of 23,000 was larger than the turnstile count for any single game back home at Comiskey Park. Not surprisingly, the imbalance of support prompted talk of a permanent White Sox move to Milwaukee.

That conversation quickly ended when Selig and Company saw an opportunity in the Seattle Pilots, who had just experienced a miserable first season that ended in bankruptcy. When a local deal to keep the team in Seattle failed, Milwaukee swooped in. With just a week to spare before Opening Day 1970, the Pilots became the Brewers, and it was 1953 all over again for Milwaukee. The move came so late, so quickly and so unexpectedly, the team continued to play in Seattle uniforms until Brewer-specific ones arrived.

Chapter Two: The Brewers.

Like a divorcee wary of a second marriage, Milwaukee fans didn’t embrace the Brewers with the same vigor as the Braves. Part of it was the bad aftertaste of the Braves, but the Brewers essentially were also a major league team in training, something clearly shown when they lost their first game at County Stadium, 12-0. It took five years for the Brewers to break a million, but until then it didn’t cost them; the rental agreement with County Stadium gave the team virtual free rent up to one million in attendance.

The fans may have been fewer, but the eccentricity remained high for those who showed. Tops on the list may have been Milt Mason, a 69-year-old diehard who, sore over the team’s weak attendance during the Brewers’ first year, made his way to the top of the County Stadium scoreboard and refused to come down until there was a sellout. After 40 days and 40 nights, Milwaukee’s Noah gladly touched terra firma when Bat Day filled the seats.

Mason, who died three years later, became the inspiration for mascot Bernie Brewer, who originally was a real person as opposed to a head-to-toe creation of foam and fur. Bernie would be perched atop an elevated shed beyond the bleachers and, whenever a Brewer bashed a home run, would slide down into a giant stein of alleged beer. Bernie eventually got a sister named Bonnie, a gorgeous blonde who swept the bases in between innings and spanked the opposing base coaches—first with a broom to the butt, then with a kiss to the cheek. Somewhere, Morganna sat up and took notice.

Bonnie lasted seven years at County Stadium, Bernie another five after that; perhaps that was real beer in the giant mug, for rumor had it that Bernie was kicked out of County Stadium in 1985 for public intoxication. For his sake, he hopefully got to be around for the seventh-inning crooning of The Beer Barrel Polka, a Brewers tradition. Bernie returned in 1993, this time as a full costumed mascot.

Atop a tall patchwork of flimsy-looking scaffolding behind the center-field bleachers was the home of mascot Bernie Brewer, whose job it was to slide down into a giant mug of “beer” whenever a Milwaukee player hit a home run. (Flickr—Ben Fenske)

With the brew came the brats. Football-style tailgating became a passion of Brewers fans, and why not? Sausage fans the world over found themselves in aromatic heaven walking the parking lots before a game, as hibachis fired up, kielbasas roasted and nutrition facts be damned. The eating didn’t stop once inside County Stadium; nearly 90,000 hotdogs were once consumed among a crowd of 45,000. That’s right: Two per person, on average.

As with Bernie Brewer, the Brewers’ marketing department didn’t skip a beat on tackling the sausage angle. The team in 1993 began a human version of dot racing, sort of; they dressed up four unlucky volunteers in tall sausage costumes and had them race around the field before the seventh inning. It’s another tradition that continues today at American Family Field.

The fans’ colorful character offset the early, blasé editions of the Brewers. With the exception of George “Boomer” Scott—about the only person who could conquer County Stadium’s distant outfield walls—the team was a no-name mix of mediocrity. The Brewers gave themselves one publicity booster shot in 1975 when, for old times’ sake as much as anything else, they brought 41-year-old Hank Aaron “home” to Milwaukee to play his final two years, punching out his last 22 homers as a fading designated hitter.

Real firepower—and personality more befitting of Milwaukee in general—brought about the glory of the Brewers’ times at County Stadium starting late in the 1970s. Suddenly, it seemed everyone in the lineup was capable of going deep, from future Hall of Famers Robin Yount and Paul Molitor to Cecil Cooper to Ben Oglivie to Sixto Lezcano to powerful slugger Gorman Thomas—whose husky frame and bushy mustache made him look like the perfect barmate for Bernie Brewer. On the mound, Pete Vuckovich—winner of a Cy Young Award in 1982—may have been the craziest man in Milwaukee; he was said to eat nails, glass, and live toads.

This unique grouping of talent helped the Brewers earn their first postseason appearance in the strike-shortened 1981 season, and broke through to their first (and, still, only) pennant a year later when they outlasted an exceptionally competitive AL East and then the California Angels in a comeback ALCS taken to the maximum five games; championship dreams fell short when Milwaukee blew a 3-2 game lead against the Cardinals in a seven-game World Series.

By then, the fans returned en masse, and the extra seats were needed as County Stadium underwent its final expansion to 53,000, wrapping the double-deck grandstands just around each foul pole. The farthest of the new seats was mirthfully reserved for Bob Uecker, the popular, self-deprecating Brewers broadcaster who once bragged about the distant view from the last row of the upper deck in a beer commercial. Blame Uecker, then, for finally blocking the view of the games from the hillside V.A. hospital nearby.

Uecker was featured in County Stadium’s lone brush with Hollywood, as the ballpark played the role of Cleveland Stadium in the 1989 film Major League. The casting call for Milwaukeeans to come dressed as Indians fans must have contained some sort of macabre appeal, and they didn’t disappoint the film’s producers hoping to see a good turnout; the nearly 30,000 who showed was double the hope.

Faithful to the End.

Over County Stadium’s final two decades, the winning subsided, the facility drifted into old age and cries of a new ballpark slowly began to grow louder—mostly from Bud Selig, whose rise to baseball power peaked in 1992 when he took over the commissionership from the ousted Fay Vincent—as accelerated free agent spending throughout baseball gradually handicapped Milwaukee’s status as a “small market” franchise that couldn’t compete with the big boys. The players, increasingly spoiled by the frills of the newer ballparks, increasingly saw the antiquity of County Stadium with scorn. Reliever Curt Leskanic once growled, the visiting clubhouse was so small, “you have to go outside to change your mind.”

Selig relinquished his role as the Brewers’ owner in 1998—handing the keys over to daughter Wendy Selig-Prieb—and his final act was to “restore” Milwaukee to the National League. Because a new round of expansion would leave both leagues with an odd-numbered 15 teams—and with baseball yet to embrace year-round interleague play—the Brewers happily volunteered to move over from the AL. It was the first time in modern history that a team had switched leagues, and it bumped attendance up even as the Brewers continued to play substandard baseball.

County Stadium during its final season of 2000. The Brewers’ stay at the ballpark was given an unexpected one-year extension after a major construction accident next door at Miller Park, County’s replacement. (Flickr—Barrel Man Sammy)

To the end, County Stadium maintained its midwestern charm as an old-fashioned, straightforward ballpark that offered the game and little else. Over the years, the venue and the 65 million fans who passed through its gates witnessed plenty of history. Three World Series. Two All-Star Games. The 300th career victory for both Warren Spahn and Nolan Ryan. Willie Mays’ four home runs in a 1961 game. Rickey Henderson’s 119th stolen base to break the season record in 1982. Robin Yount’s 3,000th hit in 1992. Harvey Haddix’ 12 perfect innings, before losing in the 13th in 1959. Paul Molitor’s 39-game hit streak in 1987, snapped when he was left on deck as Rick Manning brought in a game-winning run; the fans, rooting more for Molitor than the Brewers, booed Manning for winning the game.

The 1999 season was to be the last at County Stadium, scheduled to be demolished quickly afterward as a sacrificial bow to Miller Park (now American Family Field) next door. But it got a one-year reprieve when a fatal crane accident set back construction at the new ballpark. Everyone who bought tickets for what was thought to be the last game had to reschedule for 2000, when a packed house said goodbye to the 47-year-old facility. After an 8-1 loss to Cincinnati, the ceremonial last pitch was thrown; it was delivered by Warren Spahn and caught by Del Crandall—the same battery that opened County Stadium in 1953 for the Milwaukee Braves. “It’s time to say goodbye,” said Uecker in addressing the crowd after the game. “For what was, will always be.”

Today, County Stadium lives on through more than just memories. The field remains in truncated form, part of a petite facility named Helfaer Field that can be rented out for little leaguers, weekend warriors or pregame activities for Brewers games at American Family Field. It’s a quaint reminder of a bigger ballpark that once showed the rest of the baseball world that Milwaukee belongs.

The Ballparks: American Family Field Beer may have made Milwaukee famous, but it was County Stadium in the 1950s that showed America that baseball could play better there than anywhere else. A half-century later, American Family Field—originally entitled Miller Park—rekindled the torch and ensured its fans that the good times have indeed returned to the city with its heart restored to the National Pastime.

The Ballparks: American Family Field Beer may have made Milwaukee famous, but it was County Stadium in the 1950s that showed America that baseball could play better there than anywhere else. A half-century later, American Family Field—originally entitled Miller Park—rekindled the torch and ensured its fans that the good times have indeed returned to the city with its heart restored to the National Pastime.

Milwaukee Brewers Team History A decade-by-decade history of the Brewers, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.

Atlanta Braves Team History A decade-by-decade history of the Braves, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.