The Ballparks

Seattle Kingdome

Seattle, Washington

(Flickr—Art Codron)

It was built to last a thousand years but barely made it past the age of 20, a swirling, petrified cupcake bitten into by locals who initially loved it for firmly pinning Seattle on the pro sports map but quickly disliked once the new stadium smell wore off. The Kingdome and the National Pastime were not to be the match made in Northwest heaven, as a brand of arena baseball ensued with high fly balls ricocheting here, there and everywhere over a zipped-up chunk of fake turf.

The baby is born; the crib is its nest. The young child grows, learns to walk, and talk, and progress. Soon, the crib is outmoded and neglected.

In 1977, the infant Seattle Mariners breathed their first breaths of life, and the Kingdome would be their crib. It was a sturdy, architectural statement of the times; a domed structure thinner that it appeared, stronger than it needed to be. It was also aesthetically depressing. The Mariners struggled to mature and clung safely to their crib until they turned 15 and finally began to sprout All-Star muscle and a winning attitude. The Kingdome, the crib that was never meant to be one, no longer wanted to be associated by the Mariners, the child who had finally grown.

Most cribs live on through garage sales, but the Kingdome was too big and immoveable to be placed on a driveway with a “For Sale” sign slapped on it. Barely two decades into its existence, it suffered a worse fate—reduced to rubble by explosives in March of 2000.

The implosion made Jack Christiansen ill. The Kingdome was not his crib, but his child. The main architect behind the structure, Christiansen relied on an ingenious special process in which the roof—spanning 660 feet across and standing as high as 250 feet—would safely cover the bowl with a thickness of a mere five inches. Rather than watch his creation be destroyed from his Bainbridge Island retirement home across Puget Sound, Christiansen bolted out of town until the dust cleared. Perhaps he didn’t know what would hurt more: The sound of the concrete crashing to the earth, or the thunderous cheers from the tens of thousands who gathered to watch.

Put a Lid On It.

In the 1950s, America boasted of its new frontier—and baseball piggybacked on it, riding passenger jets and the emerging Interstates on a westward path from the Northeast. But Seattle, despite a major league-worthy population of 500,000, seemed too far off the beaten track to be an option. (Even today, the Mariners annually rack up more air miles than any other team; its nearest competitor sits in Oakland, some 650 miles away.)

The Emerald City’s relative remoteness didn’t stop local leaders from dreaming—and dreaming big. The first murmurs of a domed stadium could be traced back to 1957 when Dewey Soriano, the general manager for the Seattle Rainiers of the Pacific Coast League, told the Seattle Times that the city should build an all-purpose stadium—and “they should put a lid on it.”

The quote perhaps inspired restaurant magnate David Cohn. In 1959, he made the first formal suggestion to the Seattle City Council of a domed stadium. Within a year, the council took his thought to heart and put it on the ballot. But voters, skeptical that a domed facility would actually cost $15 million to construct and that it would be built on spec (Seattle had no major pro sports teams), defeated the measure by a 52-48 split.

Starry-eyed concepts for a stadium—including one that floated on Elliott Bay—couldn’t keep another measure from sinking in 1966. Yet the proponents fought on. When they tried again two years later, they had crucial leverage the previous two initiatives lacked: The assurance of big league baseball in Seattle, as the majors awarded the city with an expansion team months earlier. Just to be safe, pro-stadium backers flew Mickey Mantle in to help lobby support. The third time was the charm; the proposition passed. Maybe the voters thought Mantle would play for the new team.

Royally Rushed.

The creation of that new team, the Seattle Pilots, would be a double-edged sword. Seattle got their major league ballclub, but it got it too early; originally set to debut in 1971, the Pilots had to be rushed into action in 1969 because a Missouri politician (Senator Stuart Symington), stung over the loss of the Kansas City A’s to Oakland after 1967, didn’t want to wait an additional two years for the other expansion team, the Kansas City Royals, to get started and threatened legal action if they had to.

Baseball acquiesced, Symington and the Royals got their way and the Pilots were slated to spend more interim time at Sick’s Stadium—a modest, 15,000-seat home of the Rainiers built by owner and local beer baron Emil Sick in 1936. While Sick’s did the trick for the minor league Rainiers, it became woefully inadequate for the Pilots. It was hastily expanded to 25,000, the toilets didn’t flush and, although broadcasters got to see Mount Rainier from the press box, they couldn’t see down the left-field line because of structural obstructions.

The premature Pilots of 1969 couldn’t snare a local TV deal, drew only 678,000 fans, lost 98 games and a ton of money—resulting in a desperate search for new local blood to rescue them. One came forward, a handshake was consummated and a vote went to the AL owners—but approval fell shy by a single vote when Royals owner Ewing Kauffman, who likely would have said aye to the move, was back in Kansas City dealing with “more important matters.” It was a no-show that killed the Pilots.

It was no joke on April Fool’s Day 1970 when, just a week before the start of the Pilots’ second season, it was revealed that there wouldn’t be one. The Pilots declared bankruptcy, and in swooped a group of Milwaukee businessmen fronted by used car salesman Bud Selig to pick up the pieces and move the team to Wisconsin, where they are now the Brewers.

The sudden loss of baseball after a single season didn’t slow the momentum of the new stadium. While Seattle predictably sued baseball for damages, the stadium committee dealt with where to put the new facility. Seattle Center, home of the 1962 World’s Fair and the iconic Space Needle, was the sexy first choice—but strong opposition grew out of concern that some committee members, tied to downtown business interests, might profit from the placement. So it was back to the ballot box, where voters told the city and King County to look somewhere else.

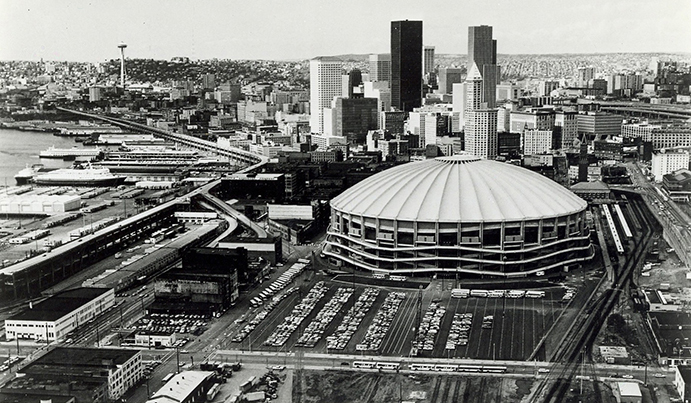

One by one, other options fell by the wayside. Finally, the committee got stuck with the last remaining—and least desirable—spot near the King Street railroad station, south of downtown in a section mixed with industry and Asian communities. The site finally approved, groundbreaking took place on November 2, 1972. The powers that be planted the first shovel into the ground. Neighborhood protesters responded by pelting them with mud.

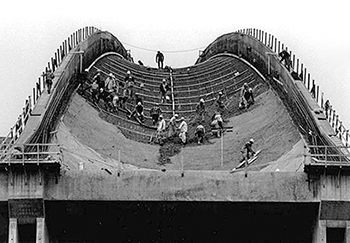

As construction commenced, the vision of Jack Christiansen’s dome design began to take shape. Working for the architectural firm Naramore, Skilling & Praeger, Christiansen used the concept of hyperbolic paraboloids, which in isolated form look like concrete potato chips, as the source for the slim, five-inch-thick ceiling. These “thin-shell concrete” structures had been invented in Europe during the early 1900s and migrated to American architecture/engineering, with wavy roof patterns identifiable to futuristic building designs of the postwar era.

Construction on the Kingdome’s paraboloid roof, which would measure a mere five inches in thickness. (The Seattle Times)

Holding the paraboloids together were 41 steel ribs that decreased in width as they approached the very top of the dome. The ribs themselves were held in place on the Kingdome’s outer walls and kept there by 324 steel cables encircling the structure as a tension ring. Keeping everything sturdily in check below were 40 massive columns driven 60 feet underground, bulked up and beyond by reinforced steel.

Not everything went so smoothly on the Kingdome build. Drake, the original contractor, fell behind schedule and then literally walked away from the project late in 1974—claiming they weren’t being paid for work beyond the original scope. King County sued Drake, and Drake sued King County; four years later, a Federal court ruled against Drake and ordered it to pony up $13 million. Though financial relief for the Kingdome, the judgment didn’t cover the increased $27 million tab weighed over its original $40 million budget.

As a multi-purpose stadium, the completed Kingdome was not going to sit lonely waiting for baseball to return; tenants had already lined up in the National Football League’s Seahawks, born as an expansion team in 1974, and the North American Soccer League’s Sounders, who helped open the stadium in April 1976 before 50,000 fans for an exhibition against the New York Cosmos and fabled star Pele with many field-level seats still yet to be inserted.

Meanwhile, Seattle and baseball continued to do battle in court over the Pilots’ departure. At some point, Major League Baseball decided it wasn’t going to get the ideal verdict and told Seattle: Drop the suit, and we’ll give you another team. That’s what the city wanted all along; and with that, the Mariners became reality.

The Kingdome was placed south of Downtown in the spot politicians least wanted to put it. Neighboring residents, mostly from Asian-American communities, didn’t want it there either. (King County Archives)

Warehouse Baseball.

Eight years after the Pilots’ last game, the Mariners played their first. Co-owning the team was Hollywood actor Danny Kaye, but not even his Walter Mitty would have wanted to dream the nightmare that was coming to Seattle’s second shot at the majors for the next decade and change. The Mariners lost their first Kingdome game with ease (7-0 to the California Angels) and never looked back, because there frequently was nobody behind them in the standings. Like the Pilots before them, the Mariners suffered 98 defeats in their first campaign; unlike the Pilots, the Mariners got a second chance to improve on it. But they failed with the opportunity, losing at the rate of 98 games a season through 1983—and then not even climbing above .500 until 1991.

There were some early moments for Seattle baseball fans to cherish. The Kingdome hosted the 1979 All-Star Game and popular Mariners star Bruce Bochte delivered a crucial RBI hit; in 1982, Gaylord Perry—creating his own farewell tour by playing for almost every major league team—highlighted his short turn as a Mariner by winning his 300th career game under the roof. But with the good came plenty of the bad for the Mariners and Kingdome baseball, even if it didn’t lack for peculiarities.

Three years before Perry’s 300th win, Willie Horton’s bid for his 300th career home run was denied by a support wire high above the field, knocking the ball straight down for a single. In 1985, Oakland’s Dave Kingman—for whom no major league facility was too big—was less lucky; his tape-measure blast was also blunted by the wire, and Mariners left fielder Phil Bradley circled underneath to make a dizzying catch. Then there were pop-ups sent high in the air that simply disappeared; it once happened to the Mariners’ Ricky Nelson, who’s sky-high fungo got caught atop a speaker hanging from the ceiling. Ozzie and Harriet would have been amazed.

Down, way down on the ground, fans once found Lenny Randle trying to blow a ball rolling slowly down the third base line foul, earning the wrath of the umpires. Perhaps Randle knew he wasn’t going to get any help from a zipper seam, because that’s the way the Kingdome turf was put together. God forbid if the turf ever left its fly open, but that’s what Bruce Bochte once complained about; he even considered filing a grievance through the players’ union but decided against it.

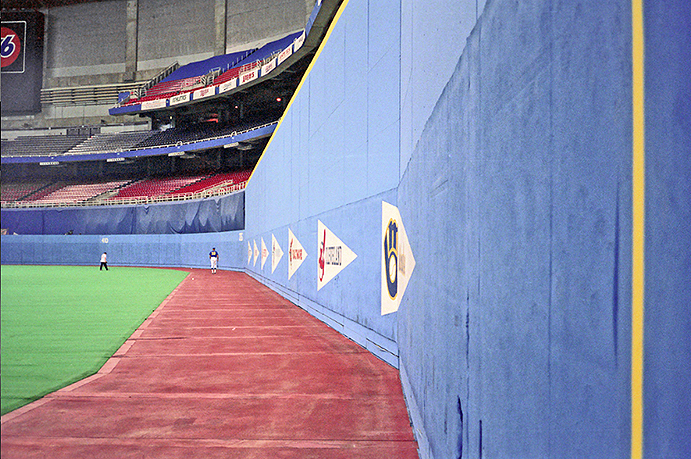

The overhanging obstructions may have saved the pitchers’ skins on occasion, but for the most part the Kingdome was genuinely unkind to them. In one of the Mariners’ early, cuter touches of marketing, the relatively short distances to the outfield walls were measured in fathoms as well as feet—and pitchers sometimes confused those feet measures with the smaller fathom numbers as deep fly outs in most other ballparks routinely became easy home runs at the Kingdome. At first, the lines ran a mere 315 feet between home plate and the foul poles; by 1981, the gaps had been shortened to a startlingly short 356 feet. “In this ballpark,” said the Angels’ Don Baylor, who stroked the Kingdome’s first-ever hit, “I feel that when you walk to the plate you’re already in scoring position.”

A year later, management made shots to right field a tad more challenging by raising the wall to 23 feet; an out-of-town scoreboard was ultimately placed within it. In a nod to their extended market, the Mariners affectionately nicknamed the West Coast’s version of the Green Monster “Walla Walla.” It may not have increased attendance but it probably brought in a few more folks from Walla Walla, 270 miles away.

To give the Kingdome some asymmetry, the right-field wall was raised to 23 feet and given a Northwest flavor by being called “Walla Walla.” (Jerry Reuss)

Seattle manager Maury Wills once messed with the dimensions himself, ordering the groundskeepers to extend the batter’s box one foot forward before a game. It didn’t take long for umpires to see something strange, and Wills was fined and suspended for two games.

While the Kingdome may have been uncomfortably cozy for pitchers, it was uncomfortably distant for the fans. The facility’s seats seemed to be designed more with football in mind, and it showed—even with field-level sections swiveled to conform to baseball. Foul territory was larger than big league norms, and the upper deck was far recessed from the action; the furthest seat away from home plate was 617 feet, a distance not even Babe Ruth with his best drive could match. Worse, numerous upper-deck seats provided only partial views of the playing field, but it was a moot point; they were rarely filled.

Reaching For the Anti-Depressants.

Initially thanked just for being around as a major league venue, the Kingdome would soon find the locals focusing less on its servitude and more on its appearance. It eventually picked up a bundle of nicknames, almost all of them derived from the mortuary business. Outside, it was often damp and gray; inside the Kingdome, it was always just gray. And that hurt on sunny summer afternoons—for which the Mariners missed out on quite a few during their time inside. In Curt Smith’s book Storied Stadiums, Mariners broadcaster Dave Niehaus reflected: “Going indoors is a pain in the ass on a beautiful day.”

The hatred for the Kingdome intensified once one entered the Mariners’ executive offices. A revolving door of regimes spun through and sought to make the Kingdome worth their while, attempting to sweeten the team’s lease and playing the St. Petersburg card if they didn’t get their way. All were rebuffed, all lost money. They all blamed the Kingdome. Never mind that the losses piled up as much on the field as they did on the balance sheet.

The talent problem was solved starting in 1989 when Ken Griffey Jr. arrived in Seattle. Junior loved the Kingdome; he homered on the first pitch he saw there. A year later, he made history with his dad, Ken Griffey Sr., when they became the first father-son duo to appear for the same team in the same game. He was a breath of fresh air who couldn’t breathe it outdoors when performing—not in Seattle, anyway—but the Mariners badly needed his presence. They got it; Griffey hit .310 over 10 years at the Kingdome, and for every 162 games he logged there, he averaged 45 homers, 128 RBIs and stole uncounted numbers of home runs from opponents by jumping high over the center-field wall.

With Griffey and two other Hall of Fame-caliber stars—pitcher Randy Johnson and shortstop Alex Rodriguez—joining the fold, the Mariners finally began injecting excitement into the Kingdome. It all culminated in 1995 when the Mariners caught fire late, overcoming a 13-game deficit to the first-place Angels by winning 17 of their last 22 games—including a tie-breaking playoff at the Kingdome against California to send them to their first postseason, where they outlasted the New York Yankees in a memorably raucous best-of-five series taken to the limit. Mariners Fever became contagious; empty seats at the Kingdome suddenly became a rare sight, and the team finally understood how loud the place could be when packed.

Doubling the Mariners’ pleasure that year was that the team’s success upped the prospects for a new ballpark at the polls—and although the initiative failed by a razor-thin margin, Washington State government overrode the vote and gave its blessing for the building soon to be known as Safeco Field.

The view of the action from the top of the Kingdome’s ceiling. (King County Archives)

Get Out—Before it All Falls Apart.

Less than 20 years old at that point, the Kingdome appeared ready to be cut down in midstride rather than be allowed to fulfill its 1,000-year mission. But the wrinkles were already starting to show.

Shortly before a game in July 1994, several ceiling tiles rained down from the concrete roof; one came perilously close to Baltimore star shortstop Cal Ripken Jr., whose consecutive game streak might have ended at 1,988 had he taken a direct hit. No one else was hurt, but the game was postponed and the Kingdome deemed indefinitely unsafe to play until the problems were fixed. Ironically, the Mariners were spared the indignity of having to play the final two months of the season on the road when, two weeks later, the 1994-95 baseball strike shut the sport down everywhere. Repairs to the roof not only cost $51 million, but also two lives when a crane failure resulted in the freefall of a basket housing two painters working at the Kingdome’s indoor apex, 250 feet above the ground.

The Kingdome held better in 1996 when a moderate earthquake struck Seattle during a Mariners game, which was postponed as engineers checked out the facility for damage. None was found, and baseball was back on the next day.

There was chatter that the Kingdome would survive after the Mariners’ departure, but when Microsoft billionaire Paul Allen bought the Seahawks in 1997, he insisted on a state-of-the-art replacement. Saying no to him would have sent the football team to Los Angeles, so Seattle said yes. The deal to build Century Link Field—which now houses the Seahawks and Major League Soccer’s iteration of the Sounders—sealed the Kingdome’s fate.

The Mariners’ lame duck session at the Kingdome, in the first half of 1999, was hardly bittersweet; the team, the fans—and the pitchers, especially—simply couldn’t wait to get out. Combined with the rise in slugging that the emerging steroid era had wrought, the bandbox dimensions had come to feel particularly smug. The Mariners and their opponents combined to hit .311, and were on pace to score more runs and belt more home runs—easily—than in any of the previous 22 seasons of Kingdome baseball.

On June 27, 1999, 56,530 fans packed into the Kingdome to bid Auld Lang Syne to the dark, dreary but durable structure they loved to hate. Appropriately, Ken Griffey Jr. hit a three-run bomb in the first inning to give the Mariners a lead they wouldn’t relinquish; when Texas slugger Juan Gonzalez later tried to match him, Griffey leaped over the center field fence and stole it. In the seventh inning, Seattle designated hitter extraordinaire Edgar Martinez showed his desire to be done with the Kingdome; he was ejected.

Shortly after the Kingdome’s final event—a Seahawks playoff game on January 9, 2000—the same blueprints used to erect the stadium were dusted off to give demolition crews a good idea of how to bring it down.

Desperate Pleas From a Father.

Jack Christiansen didn’t sit quietly as the death watch commenced on the Kingdome. The man who proudly stood by the stadium he had designed now lobbied hard to save it. He drew up sketches showing an upgraded Kingdome with added retail, offices, a new entrance and, most importantly, giant windows to let daylight in. He vented through the local media, calling the Kingdome a “durable structure with nothing like it around” and that to “arbitrarily tear it down is the most ridiculous thing I’ve ever heard of.” The only shoulders he could find to lean on were those of colleagues nationwide, who bemoaned the impending loss of a what they called a marvel of engineering, unlike anything built before or since. They cited the iconic Eiffel Tower, so initially hated by Paris locals that they wanted to tear it down, but never did.

The Seattleites weren’t as patient as the Parisians. On March 26, 2000, the Kingdome was brought down by explosives. Perhaps at that moment, Ricky Nelson’s pop fly finally fell to the ground.

In its short life span, the Kingdome faithfully played the reliable busy soldier for Seattle. Over 73 million people filed through its turnstiles to watch everything under the roof, from the Mariners to the Seahawks to college basketball’s Final Four to the Rolling Stones to Evel Knievel to Billy Graham. RV shows were commonplace; local aerospace giant Boeing once held a Christmas party over two days, and 100,000 showed. But as ugly and dour as it looked, as vilified as it was, there’s no denying that without it, the Mariners and the Seattle pro sports scene in general would be far less evolved than it is today.

The Ballparks: T-Mobile Park Chances are, there’s a thesaurus out there that lists Seattle as a synonym for the word “rain.” Perception does not always equal reality; outside of California and Arizona, Seattle is the driest major league city during the baseball season. But at T-Mobile Park, a retractable roof stands at the ready—just in case.

The Ballparks: T-Mobile Park Chances are, there’s a thesaurus out there that lists Seattle as a synonym for the word “rain.” Perception does not always equal reality; outside of California and Arizona, Seattle is the driest major league city during the baseball season. But at T-Mobile Park, a retractable roof stands at the ready—just in case.

Seattle Mariners Team History A decade-by-decade history of the Mariners, the ballparks they’ve played in, and the four people who are on the franchise’s Mount Rushmore.