THE YEARLY READER

2023: Get Them Home by Ten

New rules intended to speed up the game and increase offense lead to one of Baseball’s most transformative seasons—and ends with the wild-card Texas Rangers conquering the first world title in their 63-year history.

(Associated Press)

On the first day of Spring Training action in Florida, the Atlanta Braves were trying to unlock a 6-6 tie and defeat the Boston Red Sox in the bottom of the ninth. The bases were loaded with two outs and a 3-2 count on batter Cal Conley. Robert Kwiatkowski was ready to throw the payoff pitch. Suddenly, home plate umpire John Libka halted the proceedings. Conley began trotting exultantly toward first base, thinking Libka had docked Kwiatkowski with a game-ending automatic ball four for taking too much time. But Libka then asked Conley where he was going. Indeed, Libka had called a timing violation—not on Kwiatkowski, but Conley, for taking too long to set himself into the batter’s box.

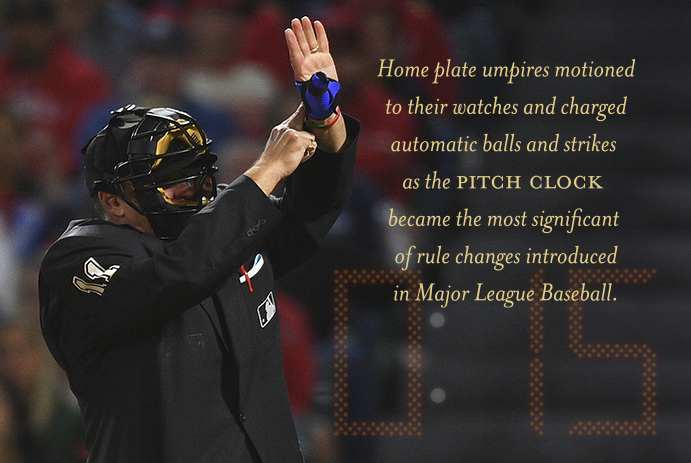

The pitch clock, the most significant of numerous rule changes instituted for the 2023 baseball season, was initially so confusing that Major League Baseball spent much of Spring Training hashing out one memo after another to the 30 teams explaining, clarifying and sometimes defending the myriad of guidelines and sub-guidelines associated with it. Faith was placed upon the pitchers and batters, once free of any time constraints, that they would gradually learn, adjust and find their rhythm with the pitch clock. They had no choice to do otherwise. Adapt, or be slapped with an automatic ball or strike, as Cal Conley found out the hard way.

For almost a decade, MLB and commissioner Rob Manfred were all but obsessed with speeding up the pace of play. Such concern was understandable. The average game had gradually slowed, from two and a half hours in the early 1980s to over the three-hour mark 30 years later. Minor adjustments—limited mound visits, intentional walks without pitches, keeping batters in the batter’s box—were made in hopes of reversing the momentum, but game times stubbornly held. Meanwhile, Manfred was using the minor leagues as a virtual lab for experimentation using more radical concepts, including the pitch clock, with agreeable results.

Dissatisfied with the continued dragging of time in MLB games—while satisfied with what he was seeing at the lower levels—Manfred in 2023 went all out on promoting many of the extreme rule adjustments to the top. To kickstart the fading strategy of stealing bases, the three infield bases were expanded in size from 15 inches to 18, while pitchers were limited to just two pickoff attempts (or “disengagements”) per at-bat. Extreme defensive shifts, which had effectively cut down on the ability of pull hitters (lefties, especially) to reach base safely, were banned as teams were now forced to station two infielders on each side of second base. And then there was the pitch clock, which decreed that pitchers must throw their deliveries no more than 15 seconds after they receive the ball with no one on base, or 20 seconds if a base was occupied. Hitters would also be on the clock; they had to be set in the batter’s box eight seconds after the pitcher received the ball. Any violation of the above rules would result in either an automatic ball called on the pitcher, or an automatic strike tagged upon the hitter.

While the larger bases, limited pickoffs and shift ban were aimed at increasing offense—which was dipping precariously toward levels akin to 1968’s “The Year of the Pitcher”—the pitch clock was all about time. It seemed odd that Manfred had to inject it into the baseball theatre when an existing rule (8.04) had been on the books for years stating that pitchers had only 12 seconds to throw their pitch. But umpires essentially ignored it—and rather than put up a fight with the arbiters on enforcement, Manfred and MLB just installed the clock to put everyone on notice and strip away the option of those on the field to feign ignorance.

When the regular season commenced, the impact of the new rules was, in a word, unmistakable.

The larger bases and pickoff restrictions made stealing bases almost too easy. The Baltimore Orioles swiped 10 bags in 10 tries over the season’s first two games—something no team from baseball’s more theft-centric eras ever managed to do. The Cincinnati Reds, who would lead the majors with 190 steals—most by an MLB team since 2009—pilfered nine in one game. That more steals weren’t attempted was eye-opening given that, by season’s end, basestealers succeeded an all-time-record 80.2% of the time.

BTW: Curiously, there were 287 successful pickoffs of baserunners in 2023—66 more than the year before, when pitchers had no disengagement restrictions. Some attributed this to newfound confidence (or overconfidence) of baserunners taking bigger leads off the base.

Stolen Bases Per Game, 1900-2023

The shift ban gave batters a bit of a boost as well. Batting averages on ground balls increased seven points to .248; the uptick was higher for left-handed hitters, whose average on grounders rose 13 points to .239. While the overall numbers were still unimpressive—more than suggesting that pitching staffs hurling increased levels of 100-MPH ‘filth’ were still in charge—the shift ban at least restored some measure of balance.

But it was the pitch clock that decidedly made for the most popular and effective change.

It did take a while for major leaguers to settle in with the timing, but the transition ultimately proved to be smooth. In April, the season’s first full month, there were 289 pitch clock violations; that number dropped with each passing month, with only 106 by September. Two out of every three regular season games didn’t have a single violation, while not one game ended on an automatic ball or strike, thankfully leading to no repeat of the Robert Kwiatkowski-Cal Conley chaos at a moment of the season when it mattered far more.

BTW: Individually, Philadelphia reliver Craig Kimbrel led all MLB pitchers with 13 violations; Washington’s Ildemaro Vargas paced all hitters with five.

The pitch clock would finally punch a hole into Rob Manfred’s pace-of-play wall of frustration. The average time of a nine-inning game dropped 24 minutes to 2:39. Thirteen games played under two hours—matching the total number of such games combined over the previous 13 years. MLB made sure that not a second would be wasted; the league even sent memos encouraging teams to fire their bat boys if they were deemed to be acting too slow retrieving bats or giving umpires a fresh set of baseballs.

The fans responded enthusiastically to the new rules and sped-up action. Attendance shot upward for the first time in 11 years with a 9.6% increase—MLB’s biggest spike since 1993—while the number of eyeballs watching regular season games on screens big and small also increased on a national, regional and streaming level.

Average Time of Nine-Inning Games, 1900-2023

The energy fueled by the new rules put a power surge into the race for the postseason, with a number of teams impressively displaying their A-game.

At the very top were the Atlanta Braves, an explosive bundle of near-peak talent fielding an MLB-best 104-58 record and featuring numerous players setting modern franchise marks: Outfielder/National League MVP Ronald Acuna Jr. (149 runs and 73 steals), slugger Matt Olson (54 home runs, 139 RBIs) and young fireballer Spencer Strider (281 strikeouts). Out in Los Angeles, the Dodgers produced their fourth straight full-season total of 100 wins, behind twin offensive threats Mookie Betts (.307 average, 39 homers, 107 RBIs) and Freddie Freeman (.331-29-102 and a team-record 59 doubles). And there was MLB’s biggest surprise, the Baltimore Orioles, riding a consistently unyielding lineup and fierce bullpen that never once suffered a series sweep during the year, finishing with the American League’s best mark at 101-61.

Dreams of a World Series showcasing either one of these remarkable ballclubs were shattered by the increasing notion that October is all about just getting a seat at the postseason table; from there, it became a matter of who was the hottest team at the moment—damn any playoff seeding, home field advantage and what you did in the regular season beforehand. As such, the Braves, Dodgers and Orioles were given a week of rest that turned them weak and rusted, quickly exiting with a combined 1-9 record and incurring the wrath of fans and pundits who bitterly complained of MLB’s money-fueled push for more wild card teams catching October lightning in a bottle at the expense of teams proving their superiority over 162 earlier games.

The Texas Rangers certainly bore much of the blame for the unexpected postseason upheaval—though for nearly half of the regular season, they could have claimed to be just as good as any of the aforementioned powerhouses.

Managed by Bruce Bochy—the three-time World Series-winning pilot for San Francisco who surprisingly came out of retirement—the Rangers shot out of the starting gate with a franchise-best 40-20 start, a vigorous state of affairs for a franchise that had averaged 98 losses over the previous two seasons in spite of a new ballpark and aggressive free-agent spending. But the seams soon began to show. A blistering offense led by veteran middle infielders Corey Seager and Marcus Semien began to stall; ace Jacob deGrom, paid a boatload of money by Texas after nine years with the Mets, befell to Tommy John surgery after six starts; and a weak bullpen made the team vulnerable in close contests, as reflected in the Rangers’ 14-22 record in one-run games throughout the year.

From that 40-20 start, the Rangers would play below .500 (50-52) for the rest of the year, yet still hung on to a 2.5-game lead at the start of the regular season’s final week—only to blow that, finishing in a tie for first in the AL West with defending champion Houston. The tiebreaker to determine the divisional crown favored the Astros, who won nine of 13 games against the Rangers.

BTW: Over their first 60 games, the Rangers had a run differential of +155. In their remaining 102 games, it was +9.

Seemingly losing their steam, the Rangers still managed to sneak into the playoffs—where Bruce Bochy could be allowed to work the same kind of underdog magic that helped elevate his Giants of 2010, 2012 and 2014 to world titles. With the 2023 Rangers, he would get help from some unlikely sources on the roster.

The Rangers began their postseason journey with a definitive two-game road sweep of Tampa Bay, owner of the majors’ fourth best record (99-63). Next in the AL Division Series, Texas shocked the heavily-favored Orioles in three straight games—handing Baltimore its first sweep of defeat all year long. Then came the AL Championship Series and a wild west duel with intra-state rival Houston—the only divisional champ out of six making it to the LCS round. It was a series where home field advantage was not to be found; the Rangers won the first two games at Houston, lost the next three at home in Arlington, then won the final two—and their third AL pennant—back at Houston.

BTW: It was the second time ever that the road team won every contest of a seven-game playoff series; the other also involved the Astros, who lost to Washington in the 2019 World Series.

While the Rangers got strong performances from expected standouts such as Seager (six postseason homers, .451 on-base percentage), outfielder/slugger Adolis Garcia (eight homers and a postseason-record 22 RBIs—15 alone in the ALCS) and pitcher Nathan Eovaldi (five wins, no losses in six postseason starts), surprise efforts came from 21-year-old rookie outfielder Evan Carter—who had only made his major league debut on September 8 and proceeded to reach base in every Texas playoff game, collecting a playoff-record nine doubles—and reliever Jose Leclerc, rising out of relative obscurity and inheriting the Rangers’ closer spot, restoring much-needed stability to the role.

Awaiting the Rangers at the World Series was a team with an even more surprising tale to tell: The Arizona Diamondbacks.

The Snakes had much in common with the Rangers: An organization two years removed from a 100-loss campaign (in Arizona’s case, 110 losses), rosy expectations for 2023, and overperformance in the season’s first half that carried them into July holding first place in a competitive NL West over two star-laden, spare-no-expense ballclubs in the Dodgers and San Diego Padres.

Embracing small-ball tactics and speed more than any other team—pacing MLB in sacrifice bunts and triples while placing second in steals—the Arizona roster provided a little bit of everything else, including NL Rookie of the Year Corbin Carroll (.285 average, 116 runs, 25 home runs, 54 steals), first baseman Christian Walker (33 homers, 103 RBIs and a Gold Glove), and a strong starting pitching duo of Zac Gallen (17-9 record, 3.47 ERA) and Merrill Kelly (12-8, 3.29) that modestly recalled Randy Johnson and Curt Schilling. An additional payoff came in the form of a preseason trade with Toronto in which the Diamondbacks acquired outfielder Lourdes Gurriel Jr. and young catcher Gabriel Moreno—stuck at the bottom of the Blue Jays’ highly competitive depth chart—for speedy outfielder Daulton Varsho. The deal paid big dividends for the DBacks; Gurriel bashed 24 homers and Moreno batted .284 with a Gold Glove behind the plate, while Varsho (.220) disappointed in Toronto.

Reality, and worse, set in for the Diamondbacks in early July as they lost 25 games in a 32-game stretch, including nine straight to start August; meanwhile, the streaking Dodgers flew past Arizona and turned a small second-place deficit into a double-digit-game lead in the NL West. At 57-59 by August 11, the Diamondbacks were threatening to fade out of the NL wild card picture—but rebounded thanks in large part to the presence of closer Paul Sewald, who not only saved a fractious Arizona bullpen but 13 of Arizona’s 27 remaining wins after being shipped by Seattle in a trade-deadline deal.

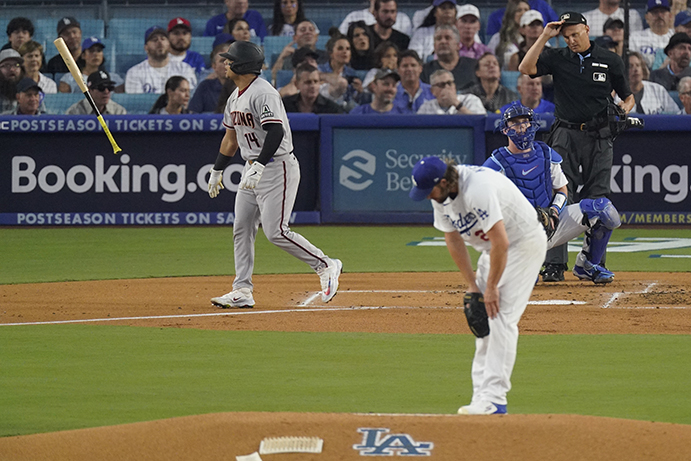

Slipping into the postseason as the NL’s low (#6) seed with an 84-78 record that salivated rather than intimidated opponents, the Diamondbacks—much like the Rangers—hit peak at the right moment. They upset NL Central champ Milwaukee in the first round with a pair of come-from-behind road triumphs, then stunned the Dodgers with a dominant three-game NLDS sweep, a series that began at Los Angeles with the DBacks handing future Hall-of-Fame ace Clayton Kershaw his worst-ever start (0.1 innings, six runs allowed on six hits).

Dodgers ace Clayton Kershaw bends downward in painful frustration, seconds after serving up a three-run homer to young Arizona catcher Gabriel Moreno; it’s the prime blow in the Diamondbacks’ six-run first inning, on their way to an 11-2 rout and stunning three-game NLDS sweep of the heavily favored Dodgers. Los Angeles was one of three teams to win 100 or more games during the regular season—and all three were summarily dismissed by wild card participants in their first round of postseason play, driving up debate on whether teams given first-round byes became too soft from the time off. (Associated Press)

Retaining their underdog status at the NLCS against the defending NL champion Philadelphia Phillies—who for a second straight year ousted the almighty Braves out of October—the Diamondbacks fought hard but looked ready to be served a TKO as the Phillies, up three games to two, headed back to Philadelphia and the confident confines of Citizens Bank Park where they had won 12 of their previous 14 postseason games. Behind seventh-year manager Torey Lovullo, the Diamondbacks shrewdly reverted to the basics that got them this far: Small ball. Over Games Six and Seven, Arizona stole eight bases, laid down a pair of sac bunts, and frustrated a star-studded Phillies lineup who continually—and wildly—chased pitches outside the strike zone. The Diamondbacks won both games and their second NL pennant by scores of 5-1 and 4-2.

Anyone who began October envisioning a World Series featuring the Braves, Dodgers, Orioles or Astros had to settle instead for a matchup pitting one team (the Rangers) with the season’s seventh-best record against another (the Diamondbacks) with the 13th. And for the first two games, #13 would look to be the lucky one. The Diamondbacks opened the series with a split at Arlington, and it could have easily been a 2-0 advantage for Arizona—but a 5-3 Game One lead was blown in the ninth inning on a crushing, game-tying homer from the Rangers’ Corey Seager; Adolis Garcia’s opposite-field strike in the 11th won the opener for Texas.

BTW: The combined winning percentage of these two teams would be the lowest seen for a final among North America’s four primary pro sports leagues since hockey’s 1991 Stanley Cup. Not surprisingly, TV ratings for the Texas-Arizona showdown to determine the ‘best’ team in baseball would be the lowest ever for a World Series.

With the series tied at a game apiece, the Diamondbacks felt good returning to Phoenix for a trio of home games. But they were forgetting one thing: The Rangers’ postseason success on the road, having already built up an 8-0 record away from Globe Life Field.

Three games later, Texas would make it 11-0.

In Game Three, the Rangers took a 3-1 victory thanks primarily to another Seager homer, this one accounting for Texas’ final two tallies. A day later, the Rangers racked up 10 early runs en rout to an 11-7 Game Four pounding, even as Adolis Garcia was forced to sit idly by with an oblique injury. Finally in Game Five, Texas emerged from six innings of scoreless dueling between the Rangers’ Nathan Eovaldi and Arizona’s Zac Gallen—who didn’t allow a hit until giving up three straight to open the seventh, allowing the Rangers to notch an ice-breaking run. Texas held its 1-0 lead to the ninth, when it exploded for four runs—the final two on Marcus Semien’s home run—to nail down the franchise’s first world championship in its 63rd year of play.

The Rangers’ Corey Seager starts a trot on his second of three World Series home runs as Adolis Garcia, on deck, triumphantly approves. Seager’s two-run shot capped an early three-run rally in Game Three at Phoenix against the Diamondbacks; the Rangers would never trail the rest of the series, won in five games by Texas for its first-ever world title. (Associated Press)

BTW: The Rangers’ world title left the San Diego Padres and Milwaukee Brewers—both of whom debuted in 1969—with MLB’s two longest active streaks of seasons since inception without once winning it all.

The postseason came and went with virtually no controversy in regards to the array of MLB’s new rules. Among 11,829 pitches thrown in the playoffs, there were only seven violations of the pitch clock—and none of those occurred in a crucial moment to ignite or kill a rally. In the end, the pundits lauding the new rules said they worked because baseball players did what they always do—adjust. Never mind that they never adjusted to hitting against extreme shifts, or that umpires never enforced Rule 8.04. It took a seismic shift—and some proverbial guns to the head—to shake them off their stubborn foundations in order for a reset to occur.

But baseball’s transformational season of rule changes, as effective and positive an impact as they made, didn’t leave everyone within the game completely happy. The players’ union asked for—and was quickly denied—a relaxation of the timing rules for the playoffs. Veteran ace Max Scherzer complained that the pitch clock was causing more injuries among pitchers—though sources doing the math found any increase in shelf time over the previous year to be negligible. Others argued for more warm-up pitches after a long rally the half-inning before, or more time for catchers to get their gear on after making the last out at the plate. Some MLB owners even bemoaned that the quicker games were cutting into food, beer and souvenir sales.

One might have believed that Rob Manfred was sitting back in his Manhattan office chair, looking back on the 2023 season and beaming with an air of complete satisfaction. But even he remained restless. He knew that players had gradually mastered the art of maximizing their allowable time; as such, the average time of game, which began in April at two hours and 37 minutes, crept upward with each passing month until it checked in at 2:44 in September. Baseball’s proactive commissioner didn’t like that; at year’s end, MLB reduced the time between pitches with runners on base by two seconds, from 20 to 18. Manfred was going to make damn sure that the typical major league game would never again surpass—let alone approach—three hours in length.

For Manfred, the bottom line demanded it.

Back to 2022: Houston Again, Honestly Five years after cheating their way to their first World Series title, the Houston Astros return to baseball’s mountaintop—this time without fraudulence.

Back to 2022: Houston Again, Honestly Five years after cheating their way to their first World Series title, the Houston Astros return to baseball’s mountaintop—this time without fraudulence.

2023 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 2023 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

2023 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 2023 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 2020s: The Turbulent Twenties Intended changes and unexpected disruption mark a time when Baseball attempts to appeal to a bigger audience, risking the loyalty of its most ardent followers. But an impressive influx of talented young players hopes to rescue the era and keep everyone happy.

The 2020s: The Turbulent Twenties Intended changes and unexpected disruption mark a time when Baseball attempts to appeal to a bigger audience, risking the loyalty of its most ardent followers. But an impressive influx of talented young players hopes to rescue the era and keep everyone happy.