THE YEARLY READER

1998: The Maris Sweepstakes

Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa enrapture the baseball world with their spectacular battle to break Roger Maris’ long-standing season home run record, while the New York Yankees make a bid to become the greatest team since the 1927 Bronx Bombers.

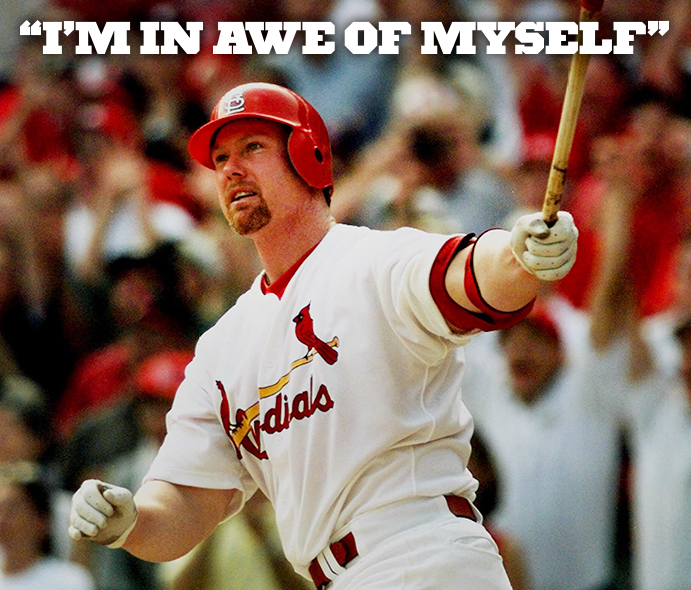

Mark McGwire surpasses Roger Maris and outlasts a challenge from Sammy Sosa to smash the season home run record, captivating an American sports public still bitterly recovering from baseball’s recent labor wars. (Associated Press)

“Do you think you’ll break Roger Maris’ record?”

This wasn’t the first time super-buffed slugger Mark McGwire had been asked the question, and it was hardly going to be the last. Reporters thought it was an apt time to ask McGwire; after all, he was on pace with Maris.

It was Opening Day. McGwire, like Maris in 1961, had zero home runs.

Throughout the 1990s, offense in the majors had shot up like Nasdaq. One round of expansion, in 1993, started the boom, which only got louder in ensuing years with a rush of new ballparks that favored batter over pitcher. It was likely to get deafening in 1998 with the addition of yet two more expansion clubs, in St. Petersburg and Phoenix.

For the moment, Roger Maris’ season home run record of 61 had remained untouched, but not without some close shaves along the way as an unparalleled glut of players popping 50-plus homers made the magic mark as approachable as ever. Now, with expansion giving another 20 minor league pitchers access to the majors for All-Star sluggers to feast on, Maris’ hallowed record stood wobbly on the verge of collapse.

And the man everyone expected to knock it down was Mark McGwire.

Since the day he first stepped upon a baseball field, McGwire had been turning heads. He hit a home run in his first little league at-bat. His high school coach attested that a teenage McGwire was bashing home runs 500 feet. After moving on to tear the rawhide off baseballs for USC and the U.S. Olympic baseball team, McGwire made a sensational imprint upon the majors in 1987 when his 49 homers for the Oakland A’s obliterated the rookie home run record.

Deteriorating play and injuries over the next five years befell McGwire, who with each successive season looked less like the next Babe Ruth and more like the next Dave Kingman, maintaining home run power at great cost—with poor batting averages and high strikeout totals. McGwire slowly got his game back in order, but the ailments worsened; a series of severe injuries limited his playing time to an average of 59 games a year between 1993-95. The frustration mounted to the point that McGwire nearly quit.

But McGwire rebounded with renewed health—and became more dangerous than ever. In 1996, he set a career high by banging out 52 homers for the A’s—in just 130 games. A year later, he reset it, blasting 58 between the A’s and St. Louis Cardinals. McGwire’s midseason trade to the Cardinals had reunited him with ex-Oakland manager Tony La Russa, and he found his new home by the Mississippi so relaxing, he re-upped with the Cardinals in 1998 for less money than what other teams elsewhere had offered. Healthy and potent, McGwire was now also content to boot. This news could hardly have been any worse for opposing pitchers, and their fears would all too quickly be realized.

McGwire went yard in his first four games of 1998. He had a three-homer performance in a mid-April contest; in mid-May, he produced another. June was barely halfway over when he had already established the mark for most homers by the end of the month, at 33.

BTW: Only Willie Mays had previously opened a season by homering in the first four games.

Like Ruth before him, the length of McGwire’s home runs was as staggering as the pace at which he was hitting them. Everywhere he went, it seemed McGwire was setting ballpark records for the longest clout ever hit. At home in St. Louis, he sent a ball 545 feet off a stadium billboard; in batting practice, he blasted a pitch straight away over the center field fence—landing in the middle of the upper deck at Busch Memorial Stadium. In Phoenix, another pre-game shot managed to find its way out of Bank One Ballpark, escaping down a street; it was never found.

In many cases, fans came to see McGwire and only McGwire. They came early to watch him hit batting practice, and left early after his last at-bat. In one game at Houston, there was a mass exodus of spectators after McGwire hit late in the contest; they didn’t bother to hang around and watch the hometown Astros stage a game-winning, ninth-inning rally.

With the pursuit of Maris’ record came the inevitable nonstop barrage of media attention. Like Maris, McGwire was a congenial and frank man with a tendency to be curt with the media; unlike Maris, he was not as caustic with reporters and knew by and large how to deal with them, even after they nosed around his locker and began asking him about supplements on his shelf that led to steroid rumors. (The drug in question, androstenedione, already banned in the minors as well as the NFL and Olympics, became illegal for major leaguers in 2004.) The media wasn’t all that bothered McGwire, subtly slighting the masses that came to see him hit batting practice—referring to himself as a “caged animal” performing in a circus. He needed something to relieve the pressure.

He got it in the form of competition.

Sammy Sosa entered 1998 as a career .257 hitter with good speed, emerging power and a reputation as a free-swinger who walked little, struck out plenty and played sloppy defense in the outfield in spite of a powerful throwing arm. When Sosa’s employer, the Chicago Cubs, made the nine-year veteran from the Dominican Republic one of baseball’s first $10 million-a-year ballplayers midway through 1997, a single word came to the minds of many within baseball: Overvalued.

The Cubs obviously knew something that the doubters did not.

Sosa was hitting well for average to start 1998 but had only seven home runs through the Cubs’ first 41 games. Then his power game exploded with an unprecedented tear in which he hammered 21 round-trippers over 22 games. By the end of June, Sosa (33 homers) had practically caught up with McGwire (37).

The dynamic Sosa was a virtual reincarnation of legendary Cubs favorite Ernie Banks with his unlimited enthusiasm. As he began to share the headlines with McGwire, Sosa gladly soaked up the national media spotlight that suddenly shined upon him. McGwire, with total media focus partially lifted off his shoulders, took note and embraced Sosa’s disposition—treating him not as a resentful combatant but as a friendly rival. For McGwire, the burden of catching Roger Maris had taken an emotionally uplifting turn.

Instead of cooling off through the summer, McGwire and Sosa both ramped it up, hardly waiting for the season’s waning weeks to start breaking records. Legends of the game were being erased from the record book by the two sluggers on an almost weekly basis. McGwire surpassed Johnny Mize as the all-time Cardinals season home run leader on July 26. Hack Wilson, for 68 years the holder of the National League season home run record at 56, was overtaken by McGwire on September 1. Wilson’s league mark was relegated to a Chicago team record—and two days later, that was gone, toppled by Sosa.

Roger Maris, and 61, was next.

McGwire led Sosa, 60-58, when the two fittingly faced off against one another for a two-game set at St. Louis starting on Labor Day. With a national TV audience—and Sosa, out in right field—watching, McGwire clobbered number 61 to tie Maris’ mark in the first game; he broke it the next night, not with a trademark titanic blast, but rather with a roping line drive that barely cleared the wall near the left-field foul pole.

So dazed by the moment was McGwire that he briefly passed the first base bag without touching it; once making contact with home plate, he saved his biggest hugs and high-fives for his son, a St. Louis batboy; Sosa, who raced in from the outfield to congratulate him; and the children of Roger Maris, who had died 13 years earlier. The ball was scooped up by a Cardinals groundskeeper—well below the reach of disappointed bleacher spectators, who paid up to $400 a ticket to be part of history—and rather than sell the ball to the highest bidder, he gave it to McGwire as part of a 10-minute ceremony that stopped the game.

BTW: The Cubs’ Steve Trachsel, who served up McGwire’s 62nd homer: “There is no joy involved. There was nothing cool about it.”

McGwire vs. Sosa

Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa piled up home run totals at a breakneck rate that exhausted even those just watching and trying to keep up with—let alone comprehend—such statistics. Here’s how both players finished each month of the 1998 baseball season with their accumulated totals to date.

McGwire had accomplished the easy task of surpassing Maris; now, with three weeks to play, he had the tougher task of outlasting Sosa.

In the five days following McGwire’s record-breaking shot, Sosa binged once more to tie him at 62. The two stayed neck-and-neck until the regular season’s final weekend, when McGwire pulled away with a prodigious flourish—slamming two homers in each of the Cardinals’ last two games, at home against the Montreal Expos, to set the new record with an improbable 70. With a few minutes afterward to finally look at the season in past tense, McGwire spoke words that bordered on self-aggrandizement, but in reality were understandably truthful: “I’m in awe of myself.”

BTW: The Expos’ Carl Pavano, who served up McGwire’s 70th: “I’ve got all winter to forget it.”

Babe Ruth’s record of 60 home runs lasted 34 years; Maris’ 61 withstood 37 years of challenge. McGwire’s 70 was a stunning figure that many felt would be safe for generations, if not forever. But offense was alive in the majors, the ballparks were getting smaller, and muscles were getting curiously bulkier throughout baseball. The days of McGwire’s grandiose record book listing were already numbered.

While two magnificent sluggers riveted a nation, the New York Yankees were quietly putting together one of the greatest campaigns in baseball history.

The Yankees lost their first three games of the year, but all it amounted to was pure aberration. They won 20 of their next 22 and 45 of their next 54 games to blast into the American League East lead with ease. From there, they hardly let up and never slumped; staying dominant to the end, they became the first team ever to clinch a postseason spot before September, and won their 100th game with 24 to play. The Yankees, by the percentages, may not have topped the 1954 Cleveland Indians—the previous AL record-holder for wins in a season—or even the fabled 1927 Yankees, who were 110-44, but in an era of free agency that induced high roster turnover, the team’s 114-48 record was every bit as impressive.

Unlike Yankee colossuses of championships past, the 1998 edition did not revolve around one or two star icons, but instead were thoroughly balanced and deep with solid star talent—new and old, prime and past. The Yankees also subscribed to the emerging concept of the global marketplace: Nearly half of the roster was foreign-born, with players representing countries as varied as Cuba, Japan, Australia, Jamaica and Venezuela.

BTW: Amazingly, no Yankees were voted to the AL All-Star team; AL manager Mike Hargrove had to select reserves and pitchers to give the team representation.

A flawless, record-breaking year for the New York Yankees (114-48) was highlighted by David Wells’ perfect game—the first thrown by a Yankee since Don Larsen in the 1956 World Series. (Associated Press)

Above all else, this Yankee juggernaut was well behaved. No bellyaches. No fights at the Copacabana. No clubhouse soap operas. No wife swapping. Just 25 mostly veteran players doing their job, and often doing it right—making life as easy for skipper Joe Torre as the so-called “push-button” managers who previously ran the Yankees. Even turbulent owner George Steinbrenner managed to keep his mouth shut for much of the year; with 114 wins, there was little to grouch about.

The closest thing to a live wire within the bunch was David Wells, a balding, portly southpaw who attended the same San Diego high school as Don Larsen—and, on May 17, became the second Yankee, 42 years after Larsen, to throw a perfect game when he retired all 27 Minnesota Twins he faced at Yankee Stadium. It was the crowning achievement in a year for which Wells finished 18-4 with a 3.49 earned run average.

More or Less

The 1998 Yankees may have set an AL season record for most wins, but you won’t find them in the record book when it comes to winning percentage. Below is a list of eight teams, legends of yesteryear playing 154-game schedules (except the 2001 Mariners, who would break New York’s victory mark)—whose frequency of winning was higher.

After completely neutralizing the offensively formidable Texas Rangers in the first round of the postseason, the Yankees received a tough ALCS test from Cleveland, trying for the second straight year to overachieve and pull off an upset of New York. The Indians got as close as anyone to performing a broadside on the Yankees, winning two of the first three games; but the inevitable took over, and a regrouped Yankee team won three straight to advance to the World Series.

Only a major upset could ruin the Yankees’ season, and the San Diego Padres had practiced well at it on the NL side of the playoffs—ousting favored 100-game winners in Houston (102-60) and, in the NLCS, the Atlanta Braves (106-56). Quite aware of their underdog status, the Padres—who included Florida Marlins castoff Kevin Brown (18-7, 2.38 ERA), closer Trevor Hoffman (53 saves, 1.48 ERA) and slugger Greg Vaughn, whose 50 home runs got lost in the McGwire-Sosa opus—were nevertheless agitated when a typically outspoken Wells predicted on ‘shock jock’ Howard Stern’s radio program that the Yankees would take the World Series in five games. Stern joked that the Yanks would win it in three.

Stern’s guess proved to be as accurate as Wells’.

As Game One starter, Wells—whose hefty tummy suggested a voracious appetite—appeared to be eating only his own words as the Padres knocked him around for a 5-2 lead through five innings. But in the seventh, New York hitting devoured Kevin Brown and a beleaguered Padres bullpen, capping a seven-run rally with a Tino Martinez grand slam. From there the Yankees never looked back. They took Game One, 9-6, jumped to a quick 7-0 lead in Game Two on their way to a 9-3 rout, stormed back late in Game Three at San Diego to win, 5-4, and finished off the sweep of the overmatched Padres in Game Four when starter Andy Pettitte and closer Mariano Rivera—who pitched 13.1 scoreless postseason innings—helped shut down San Diego, 3-0.

The Yankees’ postseason dominance—an 11-2 mark that gave them a combined season record of 125-50—brought on the inevitable yet justified comparison to their 1927 ancestors. Combined with the Mark McGwire-Sammy Sosa spectacle, the 1998 Yankees gave baseball the cure it desperately sought to mend its self-inflicted ills created with the devastating 1994-95 players’ strike. The hangover was gone, replaced with newfound magic.

The owners and players, so recently vilified, at long last were feeling the good vibes.

It once more became their burden not to screw it up.

Forward to 1999: The Umpires Strike Out Major league umpires implode with a foolhardy strategy following a series of run-ins with players and executives.

Forward to 1999: The Umpires Strike Out Major league umpires implode with a foolhardy strategy following a series of run-ins with players and executives.

Back to 1997: A Blockbuster of a Binge Florida Marlins owner Wayne Huizenga quickly builds up a winner—and just as quickly tears it apart.

Back to 1997: A Blockbuster of a Binge Florida Marlins owner Wayne Huizenga quickly builds up a winner—and just as quickly tears it apart.

1998 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1998 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1998 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1998 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1990s: To Hell and Back Relations between players and owners continue to deteriorate, bottoming out with a devastating mid-decade strike—souring relations with fans who, in some cases, turn their backs on the game for good. Recovery is made possible thanks to a series of popular record-breaking achievements by ‘class act’ stars.

The 1990s: To Hell and Back Relations between players and owners continue to deteriorate, bottoming out with a devastating mid-decade strike—souring relations with fans who, in some cases, turn their backs on the game for good. Recovery is made possible thanks to a series of popular record-breaking achievements by ‘class act’ stars.