THE YEARLY READER

1989: Of Triumph and Tragedy

In a rough year for the game, Pete Rose is banned, a popular commissioner dies, a player’s inspirational comeback from cancer is stopped cold and the local euphoria of a Bay Area World Series is badly shaken up by a major earthquake.

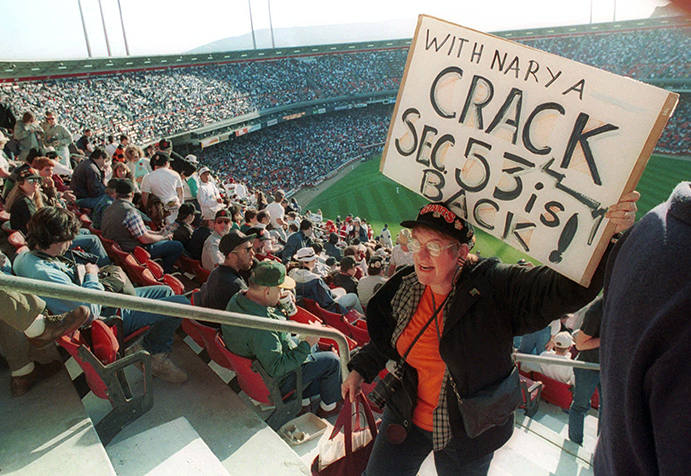

Ten days after a major earthquake rocked—yet failed to bring down—San Francisco’s Candlestick Park, the Bay Bridge World Series between the Giants and Oakland A’s reconvenes before a packed house full of resistant fans looking to refocus on baseball. (Associated Press)

The renaissance of baseball was now complete. Awakened in the mid-1970s after an archaic deep sleep in the 1960s, the game was embraced like it hadn’t been for 40 years; attendance was constantly on the rise, memorabilia sales were booming, and the game was fervently waxed nostalgic from Hollywood to the New York publishing world.

But in 1989, baseball endured a seemingly endless string of challenges, some self-inflicted, others not, that put its newfound sentimentality at risk. It was a reminder that, no matter how glossed over the sport could get with old-timers’ games, Brooklyn Dodgers paraphernalia and mint-condition Mickey Mantle cards, there were still troubles in modern times.

Before the year was out, baseball would witness the defrocking of its favorite son and its cynical link to a popular commissioner’s death, a heartbreaking end to a gutsy comeback, and a World Series jolted to its knees by Mother Nature.

Even before the gates flew open for spring training, there was plenty of bad press to go around. The owners had just gotten socked, again, by a court ruling finding them guilty of further collusion against potential free agents. Wade Boggs, the prevalent American League batting champion, was ratted on by a former mistress who told—and showed—all for Penthouse. And Steve Garvey, the retired but still-popular baseball icon, had his “Mr. Clean” image dirtied up with a series of paternity suits.

BTW: A memorable bumper sticker in the San Diego area read: “Steve Garvey is not my Padre.”

Because baseball cares more about what happens between the lines, the commissioner’s office had little use for such bedroom gossip. But it grew alarmed at allegations that were far more brooding: That Pete Rose, the game’s all-time hit leader, was betting not only on baseball, but on the Cincinnati Reds—the team he managed.

Rose was initially queried by outgoing commissioner Peter Ueberroth, who seemed content with Charlie Hustle’s answers. But he kept the case open and handed it to his successor, A. Bartlett Giamatti. A perfect choice to lead baseball in the day and age, Giamatti was a former Yale University president who spoke romantically of the game in poetic tones. Along with deputy commissioner Fay Vincent—whose dour, drone-toned façade was a sharp contrast to the whimsical Giamatti—the new commissioner hired former FBI mob investigator Robert Dowd to check further into Rose’s gambling past.

At 2,300 pages and a cost of $3 million, the so-called “Dowd Report” painted Rose as a troubled man with a bad habit of befriending shady characters such as bookies and drug dealers. More troubling was the evidence; betting slips were produced showing Rose had repeatedly bet on baseball games—including those involving the Reds—in 1987. And that, according to those interviewed, was just the tip of the iceberg.

BTW: According to the slips, Rose always bet on the Reds to win.

The investigation remained quiet until Sports Illustrated publicly blew the lid off the story during spring training when one of Rose’s disgruntled bookies, Ron Peters, sang like a canary. Suddenly, Rose became a prisoner in his own dugout, trapped by a daily arc of reporters. His evasiveness to questions on the subject seemed peculiar for a man who often and gregariously spoke his mind.

As spring turned into summer, Rose appeared ready to buckle under the weight of the evidence when he got legal leverage from an unlikely source: Giamatti. The commissioner, whose job it was to be independent until all the facts were in, had decreed Ron Peters’ testimony to be truthful—and that opened the door for a series of court battles in which Rose’s lawyers charged that baseball had an anti-Rose agenda.

The fierce tug-of-war segued into negotiations, and then to settlement. On August 24, it was announced that Rose was indefinitely banned from baseball, though he could apply for a reinstatement within a year. In exchange, baseball could not claim Rose bet on baseball, leaving a contradictory smell to the deal. The irony was hardly lost on Giamatti, who dropped the jaws of Rose and his lawyers when, at the press conference to announce the ban, answered the one question he wasn’t supposed to: “I have concluded that he (Rose) bet on baseball.”

Having to banish a living legend like Pete Rose was not what Giamatti, the idealistic Ivy Leaguer, had in mind when taking over the commissioner’s office. Recovering from the emotional and physical burden of the Rose drama one week after its conclusion, Giamatti—a known chain-smoker—suffered a fatal heart attack at his Martha’s Vineyard retreat. The renaissance sport had lost its renaissance man; Fay Vincent took over as baseball’s commissioner.

BTW: Pete Rose released a statement after Giamatti’s death, saying he was deeply saddened and had “great personal respect” for him.

Who Would’ve Bet on This?

Cincinnati finished second under manager Pete Rose from 1985-88—the years baseball alleged that Rose was betting on the Reds. Whether Rose’s gambling habits affected his managerial decisions is debatable, but here are the facts of how close the Reds challenged for first place.

Distracted by the Rose affair and wracked by injuries, the Reds stumbled to fifth place in the National League West, conquered for the second time in three years by the San Francisco Giants.

After falling a game short of a World Series appearance in 1987, the Giants were older, wiser and more talented in 1989. The continued evolution of first baseman Will Clark was expected—he hit .333 with 23 home runs and 111 runs batted in—but unexpected was the sudden rise of outfielder Kevin Mitchell, who exploded after three years of displaying erratic potential with a NL-high 47 homers and 125 RBIs. Together, Mitchell and Clark not only formed a 1-2 punch worthy of Willie Mays and Willie McCovey, but also one among NL Most Valuable Player voters, with Mitchell edging out Clark.

A human interest story developed out of the Giants’ pitching staff in Dave Dravecky. A reliable southpaw traded (along with Mitchell) from San Diego in 1987, Dravecky was diagnosed with a tumor in his pitching arm at the end of 1988 and had it removed—along with half of his deltoid muscle. Doctors were convinced the procedure would severely curtail his arm mobility and end his pitching career, but they were stunned to later see Dravecky miraculously rehabilitate beyond their expectations, and the impossible became possible when Dravecky started throwing a baseball with little velocity loss.

Quickly, impressively and cautiously working his way back through the Giants’ minor league chain, Dravecky was given the go-ahead to make his first major league start of the season, August 10 in San Francisco against the Reds. With the national spotlight upon him, Dravecky was magnificent, firing seven shutout innings before tiring in the eighth, the Giants holding on for a 4-3 win.

BTW: Pete Rose, two weeks shy of his banishment, on Dravecky: “It’s great for him. I hope he loses.”

In his second start after a comeback from cancer, San Francisco’s Dave Dravecky writhes in pain after breaking a bone in his pitching arm. The cancer would return and lead to an amputation of his entire left shoulder and arm.

A bone in Dravecky’s pitching arm, structurally weakened by the tumor surgery, had snapped. Dravecky was carried off on a stretcher and later vowed he’d return to the mound. Doctors predicted a possible return for the postseason, but the euphoria had been sapped.

After taking the West, the Giants won a spirited NLCS in five games against the NL East champion Chicago Cubs, highlighted by a spectacular individual dual between the teams’ young, star first basemen: Clark for the Giants, and sophomore Mark Grace for the Cubs. Grace repeatedly hammered at Giants pitching by hitting .647 (11-for-17) with three doubles, a triple and a home run. Yet Clark not only was slightly better (13-for-20, three doubles, a triple and two home runs), but also made his hits count—including a grand slam that pulled the Giants away in Game One, and a two-run, two-out single off Cubs closer Mitch “Wild Thing” Williams in the eighth inning of Game Five to clinch the series. Yet even in jubilation, the Giants found sadness; Dave Dravecky re-broke his fragile arm when he got caught too deep in the mob of celebrating Giants players.

While the Giants were thrilled to be back in the World Series for the first time in 27 years, across the bay in Oakland, the Athletics were fiercely determined to get back to the Fall Classic after enduring off-season nightmares over their upset Series loss to Los Angeles the year before.

Despite injuries to key players—including Jose Canseco, who missed nearly 100 games to a broken wrist—the A’s never slowed in pursuit of their second straight AL pennant. The team’s hitting, affected the most by injury and far from proficient, was backed up by a healthy and very sharp four-man pitching rotation (Dave Stewart, Mike Moore, Storm Davis and Bob Welch) that combined for 76 wins and just 35 losses.

Crucially, the A’s made the midseason steal of the year when they brought back Rickey Henderson, struggling and stewing under New York Yankees manager Dallas Green. Reacting like a free man in green-and-gold, The once-and-current Athletic tore apart the AL in the season’s second half, batting .294 with 72 runs and 52 stolen bases in just 85 games.

BTW: Henderson hit just .247 in 65 games at New York before being traded.

Go Home, Ex-Yankee

After struggling and whining through the first half of the season with the Yankees, Rickey Henderson was granted a trade back to Oakland, where he first made his mark as a major league star. Henderson’s second tour of duty with the A’s clearly rejuvenated his game.

With everyone healthy for the postseason and Henderson at the top of his game, the A’s—who had won 99 games through all the aches and pains of the regular season—were now ready to shift into juggernaut mode. Against the feisty Toronto Blue Jays in the ALCS, the A’s exhibited all their strengths. Dave Stewart won two games, closer Dennis Eckersley saved three and Jose Canseco hit a memorably titanic home run into the upper deck of Toronto’s brand new Skydome. But above them all was Henderson, who drove the Blue Jays absolutely crazy—batting .400 (6-for-15) with seven walks, eight runs, two home runs and eight steals. Bellicose Blue Jays manager Cito Gaston desperately resorted to mind games toward the end, accusing Oakland players of showboating and cheating, but the A’s laughed him off and took the series in five.

For three years, talk of a Bay Bridge World Series had grown among Bay Area baseball fans watching their local teams emerge through the late 1980s. And after two decades of being told their region couldn’t support two teams, they now had the ultimate showcase all to themselves to brag about.

Unfortunately, that showcase would be upstaged by a more traditional Bay Area phenomenon: The San Andreas Fault.

The first two games of the World Series, baseball’s first intra-market pairing since 1956 when the Yankees and Brooklyn Dodgers squared off, reconfirmed how focused the A’s were at purging the ghost of Kirk Gibson. Terrific pitching silenced the Giants’ bats at Oakland by scores of 5-0 and 5-1.

Game Three was moments away from beginning on an unusually warm and still evening at typically arctic Candlestick Park. As fans were taking their seats and players biding their time before introductions, a loud roar was heard—quickly followed by ominous movement underneath. The light towers and the second deck swayed and danced with one another above the box seats as the shaking continued for 15 seconds—or, in earthquake time, an eternity.

When it ended and all was safe, the fans heaved a huge sigh of relief, then let out a big cheer. They expected the game to go on, but the power was out and police, using bullhorns from the field, told spectators to leave the stadium at once.

As the fans exited, listening in on transistor radios and seeing a sky dotted with plumes of smoke, they realized this was no tremor.

Registering 6.9 on the Richter scale, the Loma Prieta Earthquake killed 65, injured 3,000 and caused over $10 billion in damage. A double-deck freeway near the Oakland Coliseum collapsed; the Bay Bridge, the very symbol of this World Series, was fractured. Among the homes heavily damaged in the hard-hit Marina section of San Francisco was that of A’s pitcher Bob Welch.

Because Candlestick Park was built on bedrock and had just undergone a $28 million seismic retrofit, a catastrophe of epic proportions was averted and all 62,000 people within the stadium safely departed. Outside of Candlestick, the World Series helped save more lives; many people had gone home early to catch the game on TV, and thus the usually jammed freeways were light at 5:04 p.m. on October 17.

Commissioner Fay Vincent, whose naturally downcast demeanor perfectly mirrored the moment, was happy to give the World Series a week off while the Bay Area recovered—but had to armwrestle with San Francisco mayor Art Agnos, who demanded and got an additional three days’ delay.

BTW: Vincent reluctantly agreed, but not before he threatened to move the series to Los Angeles—the ultimate insult to Bay Area baseball fans.

The World Series—and the Oakland rout—resumed on October 27 at Candlestick, as offensive firepower picked up where the pitching left off. The A’s crushed five home runs in a 13-7 Game Three thrashing, and jumped to an 8-0 lead in Game Four before surviving a late Giants counter-offensive to win the Series, 9-6. With the final out, the A’s celebrated as any team normally would, running and leaping upon one another, but most of the fans simply applauded, said “nice job” and went home to resume their post-quake lives.

Mercifully, the year was done, yet its legacy persisted. Players declared free agency, and the owners actually paid heed to them. Bay Area residents rebuilt and moved on, understanding that the ground will occasionally shake beneath them. Cancer redeveloped in Dave Dravecky’s pitching arm; by 1991, with the disease spreading, doctors had no other option but to amputate his left shoulder—though with sheer will and a strong spiritual conviction, Dravecky has become a highly respected and better man.

The same cannot be said for Pete Rose. He was stripped of all contact with baseball, and his freedom wasn’t far behind; in 1990 it was the IRS’ turn to dog Rose, who was convicted on tax evasion and sentenced to six months in jail with a $50,000 fine.

After 15 years of fiercely proclaiming his innocence, Rose performed an about face and admitted that he had, in fact, bet on the Reds in the late 1980s. He made his long-overdue contrition the only way he knew how; on his own terms, as part of a million-dollar book deal. Baseball was not impressed, and Rose remains banned while he gruffly and eagerly seeks reinstatement. The issue remains a white-hot topic of debate. His supporters say he’s suffered enough—and besides, he bet on his Reds to win, so what’s the harm? Plenty, say his detractors. Rose could have impulsively adjusted his lineups and pitching assignments when money was on the line at the expense of a 162-game focus.

For a team that finished second in the NL West four straight years under the stewardship of Rose, it begs to wonder: Did Rose’s passion for the betting line unintentionally scuttle the Reds’ chances for a World Series as much as those purposely thrown away by the 1919 Chicago Black Sox?

Forward to 1990: The Dynasty Dies Nasty Armed with a tough, rough and rowdy trio of relievers, the Cincinnati Reds knock off the almighty Oakland A’s.

Forward to 1990: The Dynasty Dies Nasty Armed with a tough, rough and rowdy trio of relievers, the Cincinnati Reds knock off the almighty Oakland A’s.

Back to 1988: Roy Hobbs in Dodger Blue Kirk Gibson makes like Robert Redford and gives the Los Angeles Dodgers a storybook ending.

Back to 1988: Roy Hobbs in Dodger Blue Kirk Gibson makes like Robert Redford and gives the Los Angeles Dodgers a storybook ending.

1989 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1989 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1989 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1989 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1980s: Corporate Makeover Baseball enjoys a healthy boom on several fronts, with increased attendance, corporate sponsorship and memorabilia sales; players also continue to enjoy skyrocketing salaries, but some abuse their newfound riches by delving into illegal drugs.

The 1980s: Corporate Makeover Baseball enjoys a healthy boom on several fronts, with increased attendance, corporate sponsorship and memorabilia sales; players also continue to enjoy skyrocketing salaries, but some abuse their newfound riches by delving into illegal drugs.