THE YEARLY READER

1961: The Greatest Feat Ever Performed*

Controversy arises over Roger Maris’ pursuit of Babe Ruth’s season home run record in baseball’s first 162-game schedule—as commissioner Ford Frick is determined to place an asterisk on any mark achieved after 154 games, the former regular season standard.

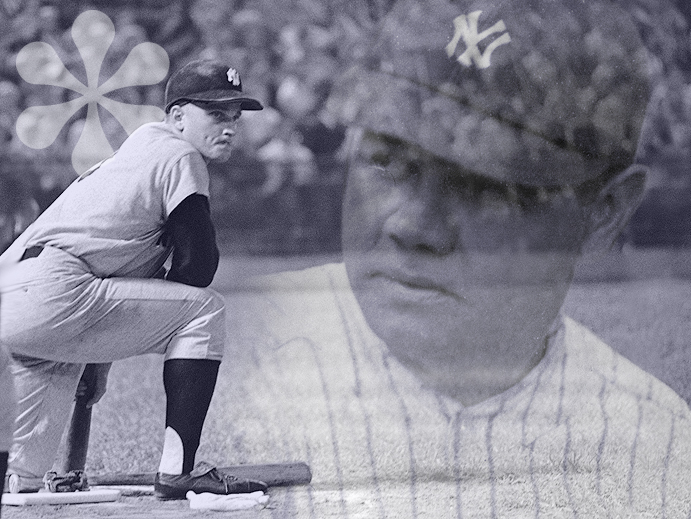

The pressure of chasing the ghost of Babe Ruth and his season home run record was enormous enough on Roger Maris; chilly fan support and a skeptically biased commissioner didn’t help. (Associated Press)

* The devil is in the details, the fine print. And for Roger Maris, an honest but hardened 26-year old just trying to go about his business, the devil’s advocate would be Ford Frick.

Baseball’s third commissioner, Frick—who eerily looked like the first, Kenesaw Mountain Landis—would oversee two kinds of expansion in 1961. One would be the introduction of two new American League franchises in Los Angeles and Washington, the latter a new and not-so-improved replacement for the Minneapolis-bound Senators. The other would be the extension of the AL’s regular season from 154 games to 162. (The National League would follow suit a year later.)

As the season began with the majors’ first expansion of the century, there was no concern, yet any mention, of how the longer schedule might play havoc with the record book. But as New York Yankees teammates Maris and Mickey Mantle both advanced an impressive assault on Babe Ruth’s season home run record of 60, Frick—Ruth’s former friend and ghostwriter—would make a sudden and controversial decision that rained on the parade.

Thus, what would be the greatest year for Roger Maris also doubled as the worst experience of his life.

Born in Minnesota, Maris grew up in Fargo, North Dakota, where he excelled in three sports: Football, track and baseball. He was offered numerous college football scholarships but chose instead to pursue a baseball career, not wanting to be locked up in a classroom for another four years. Self-confident of his talent and stubborn as an ox, Maris was signed by the Cleveland Indians and relentlessly dictated his own path through the minors to the parent club, refusing assignments he felt were beneath him, then clashing with managers who didn’t play him every day. After making a decent impression as a rookie in 1957, he was sent a contract with a $1,500 raise by Indians general manager Frank Lane. An insulted Maris sent it back to Lane torn in half.

Keeping a quiet yet studious eye on Maris all along were the Yankees, desperate for a left-handed pull slugger. And when the Indians traded Maris to the Kansas City A’s—a team often joked as being the Yankees’ top farm club, given the numerous trades between the two for which the Yankees always seemed to get the better of’—many believed it was just a matter of time before Maris was wearing pinstripes.

Sure enough, after a year and change at Kansas City, the Yankees got Maris. The trade didn’t sit well with Maris, who had happily settled with his family in Kansas City and had an aversion to big city life. The immense and often cutthroat New York press caught wind of Maris’ opinion, beginning a relationship that would be anything but congenial. But Maris won over the Yankees with his play, earning AL Most Valuable Player honors in 1960 with a 39-homer, 112-RBI campaign that many considered to be a breakout performance.

They had no idea.

BTW: Though considered another lopsided trade, the Maris deal gave Kansas City Norm Siebern—who would give the A’s several very productive years.

As 1961 began, the harsh New York media spotlight was pointed not on Maris but Ralph Houk, the team’s new manager after the purging of senior citizen and press favorite Casey Stengel. It didn’t help Houk that his team sputtered from the start. The Yankees struggled badly in spring training, were shutout at home on Opening Day by the Minnesota Twins—the awful team formerly known as the Senators—and by late May were barely above the .500 mark. Roger Maris was in sync with early Yankee misfortunes, batting as low as .208 with just three home runs through the team’s first 28 games. Rumors quietly began swirling that Maris was headed for the trading block.

Then Maris connected. Then he connected again. Then again and again. Over a 38-game span he smacked 24 home runs, bolting ahead of Mickey Mantle—who had gotten off to a flying start—for the AL home run lead. It would be the beginning of a healthy competition between two teammates built out of admiration and respect for one another, one that would raise the ante and pull them away from other slugging contenders (Jim Gentile, Harmon Killebrew, Rocky Colavito) whose bats suddenly sprang to life in an expansion-aided, round tripper-happy season.

As talk accelerated of Babe Ruth’s record teetering on the brink of extinction, Commissioner Frick suddenly saw a defense for the legendary Sultan of Swat: The 162-game schedule. He declared that any new home run record was fine with him—so long as it was hit within 154 games. Anything beyond that would be considered extra, not equal, opportunity—and would such be notated in the official record book alongside the old record with a “distinctive mark.”

Frick’s decree sent off an avalanche of media response—most of it, actually, in the commissioner’s favor. But even those who agreed wondered aloud about the timing of the announcement, opining that an edict could have been made when the 162-game schedule was introduced, instead of waiting until midseason with sacred records suddenly in jeopardy. Any denial of favoritism from Frick came off as transparent.

The media intensity played differently on Maris and Mantle. Mantle was a player and press favorite who, after 10 years with the Yankees, knew how to handle reporters. Maris, on the other hand, was the newcomer, the outsider—and not the kind of naïve, starry-eyed kid who would roll in from the countryside with an “Aw, shucks” attitude. He was often reluctant to answer questions, was blunt when he did respond, and sometimes verbally rebuked reporters for asking questions he considered dumb.

BTW: Most Yankees players even publicly said they favored Mantle to break the record, revering his standing as team leader.

In late August, shortly after Maris became the first player ever to hit 50 home runs before September, the usual ailments began to catch up with Mantle, and he soon faded from the home run chase. This, combined with the Yankees’ pulling away from second-place Detroit for the AL pennant, put enormous media focus squarely on Maris—who didn’t need it.

Without the benefit of having the New York front office provide a buffer between Maris and the press (as would be done 37 years later for Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa), Maris was all alone on the front lines of the continued media grilling. His stiff-armed attitude, misunderstood or otherwise, only made it easier for reporters to cast him as a villain trying to topple a hero’s record. Stories were planted of Maris and Mantle as warring rivals feuding over the home run chase, unaware or uncaring that the two were amicably rooming together along with Bob Cerv in a Queens apartment. The pressure became so intense, an exhausted Maris bordered on a nervous breakdown—and clumps of his blonde crewcut hair began to fall out. The man was only 26.

BTW: Mantle would eventually speak of Maris: “There may have been better players, but there was no better man.”

Through all of this, Maris continued to hammer away toward 60. With Frick’s “distinctive mark” in mind, people were less concerned about whether Maris would break the record as whether he would do it within 154 games. Maris entered game 154 at Baltimore with 58 homers; he sent one into the bleachers in his first at-bat to close within one of Ruth. Two at-bats later he sent another shot with home run distance—but it hooked foul. His next contact initially looked headed into the right-field seats, but gusty winds blowing in kept it short of the wall. It was Maris’ best and last chance; Ruth’s record, within 154 games, was safe.

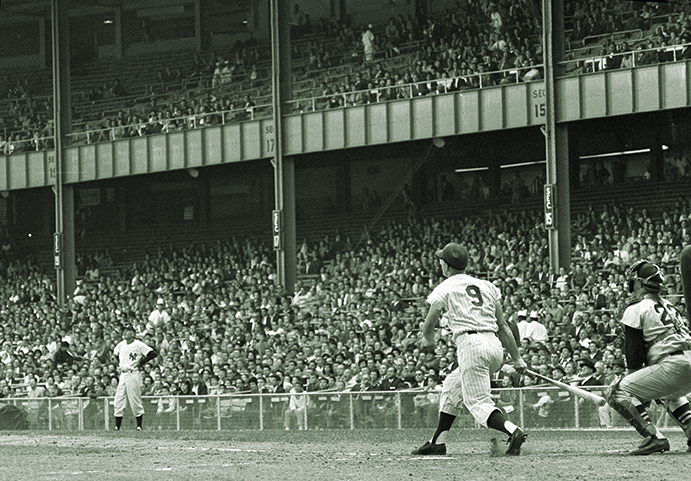

Suddenly, everyone laid off Maris. He knocked no. 60 out of the park four games later at Yankee Stadium against the Orioles, and on the final day of the regular season, Maris hit the record-breaker off of Boston’s Tracy Stallard and into the right field bleachers. There was no stopping of the game, no ceremony. There were 44,000 empty seats at Yankee Stadium; of the 23,000 others that were filled, none was occupied by Ford Frick. The Yankees literally had to push a humble yet happily relieved Maris out of the dugout to take a curtain call. Maris had his record, but Ruth still had his. Everyone was happy. Sort of.

Roger Maris launches his 61st home run to surpass Babe Ruth. An opportunity to witness history apparently wasn’t a selling point for New Yorkers; Yankee Stadium was barely a third full to watch Maris’ milestone. (Associated Press)

Maris’ 61 home runs served as more of an empowerment than a distraction for the rest of the Yankees. Their 109-53 record was the franchise’s best showing since 1939, and the extra eight games nearly allowed them to equal the fabled 1927 Yankees in victories.

Thanks to Maris and Mantle—who finished the year with a combined 115 home runs—the Yankees as a team set a then-record with 240, as Bill Skowron, Yogi Berra, Elston Howard and Johnny Blanchard each added 20-plus blasts. Ralph Houk chucked away Casey Stengel’s platooning routine, and allowed Whitey Ford to finally take the mound every fourth turn; Ford responded with his best year ever, setting career highs in victories (25), winning percentage (.862) and innings (283).

BTW: Yes, the Yankees broke the old mark within 154 games.

Ford Frick Can’t Spit on This One

By combining to hit 115 home runs in 1961, Roger Maris and Mickey Mantle set an all-time record for the most round-trippers by teammates in one year. So everyone could be satisfied, they toppled the old mark—set by Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig in 1927—before the 154th game of the season.

The Yankees were so dominant and, thanks to Maris and Mantle, held such a monopoly on press coverage, the Cincinnati Reds must have felt like the Washington Generals prepping for the Harlem Globetrotters when they came to New York to start the World Series.

Any success the Reds had over the previous 10 years seemed to come courtesy of their power hitting abilities, as led by young slugger Frank Robinson. But it was pitching that finally transformed Cincinnati into a pennant winner in 1961 after finishing a distant sixth in 1960. Leading this stunning rise on the mound was Joey Jay, who led the National League with 21 wins (against 10 losses) after never having won more than nine in seven previous years at Milwaukee; and 24-year-old lefty Jim O’Toole, who matured with a 19-9 record and 3.09 earned run average that was best among Cincinnati starters.

The Reds came away with a split of the first two World Series games at Yankee Stadium, but that’s as good as it got for Cincinnati. Moving on to Crosley Field, the Yankees got hotter with each passing game to dispose of the Reds in five. Game Three was decided in the top of the ninth, 3-2, when Maris hit his only Series homer; the Yankees took total control in Game Four when they blanked the Reds, 7-0; and New York locked up the Series in Bronx Bomber fashion in Game Five, scoring 11 runs in the first four innings before settling into a 13-5 rout.

After carrying the team on their backs throughout the regular season, a largely ineffective Maris (two hits in 19 at-bats) and injured-plagued Mantle (one single in two games) were picked up by the rest of the Yankees against the Reds. Second baseman Bobby Richardson had his second straight outstanding Series, leading the Yankees with nine hits; backup catcher Johnny Blanchard hit two home runs and a double; and Whitey Ford pitched 14 scoreless innings to extend his World Series streak to 32, breaking the old record—held by Babe Ruth. As historian Robert Creamer would mention years later, 1961 “was a bad year for the Babe.”

BTW: Richardson had knocked in a Series-record 12 runs in 1960.

The Thrill is Gone

After bombing away at the record book, Roger Maris and Mickey Mantle simply bombed in the 1961 World Series—and didn’t fare much better over the next three Fall Classics, until Mantle gave it one last hurrah with an 8-for-24, three-homer binge in 1964. Overall, it was a sign that the M&M Boys’ best days were behind.

Ultimately, people would grow accustomed to the 162-game schedule and, as short-term memory usually dictates, the passion of the argument over the longer schedule would subside. As a result, history would look more favorably on Roger Maris’ spectacular 1961 effort to the point that, in 1991, Ford Frick’s asterisk placed alongside Maris’ 61 homers would officially be purged from the record book.

If there was a heaven, it was the only way Maris would know. He had died six years earlier of lymphatic cancer at the age of 51.

Forward to 1962: Lined to Second Best The New York Yankees’ Ralph Terry barely avoids being labeled a World Series goat for the second time in three years.

Forward to 1962: Lined to Second Best The New York Yankees’ Ralph Terry barely avoids being labeled a World Series goat for the second time in three years.

Back to 1960: A-Maz-ing! The Pittsburgh Pirates become one of the game’s unlikeliest champions with a historic walk-off home run by Bill Mazeroski.

Back to 1960: A-Maz-ing! The Pittsburgh Pirates become one of the game’s unlikeliest champions with a historic walk-off home run by Bill Mazeroski.

1961 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1961 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1961 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1961 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1960s: Welcome to My Strike Zone In a decade where baseball as a tradition is turning stale with America’s emerging counter-culturism, major league owners see its biggest problem to be, of all things, an overabundance of offense in the game. The result? An increased strike zone, further contributing to a downward spiral in attendance, but greatly aiding an already talented batch of pitchers.

The 1960s: Welcome to My Strike Zone In a decade where baseball as a tradition is turning stale with America’s emerging counter-culturism, major league owners see its biggest problem to be, of all things, an overabundance of offense in the game. The result? An increased strike zone, further contributing to a downward spiral in attendance, but greatly aiding an already talented batch of pitchers.

Cuno Barragan reflects on a short but memorable career that included a home run in his first at-bat, manning the scoreboard to steal signs and his experience playing for the Chicago Cubs’ College of Coaches.

Cuno Barragan reflects on a short but memorable career that included a home run in his first at-bat, manning the scoreboard to steal signs and his experience playing for the Chicago Cubs’ College of Coaches. Hal Naragon recalls signing underaged with Bill Veeck and the Indians, handling star pitchers from behind the plate, and his eye-opening experience moving with the Washington Senators to Minnesota.

Hal Naragon recalls signing underaged with Bill Veeck and the Indians, handling star pitchers from behind the plate, and his eye-opening experience moving with the Washington Senators to Minnesota.