THE YEARLY READER

1957: If Casey Had a Hammer

The Milwaukee Braves, with solid pitching and a potent line-up that includes Hank Aaron, become the first team outside of New York City to win a World Series since 1948.

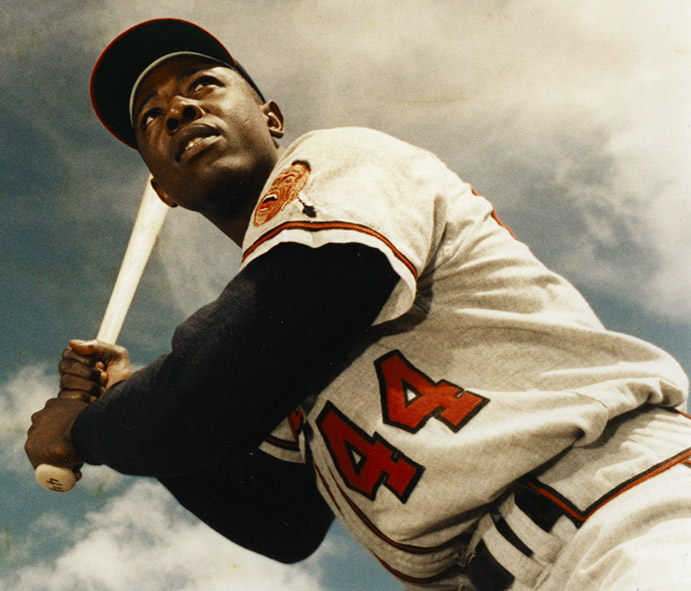

After a tormenting experience in the South playing in the minors and absorbing racial abuse, Hank Aaron settled into a far more peaceful existence in Milwaukee—and his shining play helped give the city its first world championship. (The Rucker Archive)

For six years, Casey Stengel had watched Mickey Mantle, his teacher’s pet, gradually rise from prospect to star to superstar, his triple crown performance of 1956 confirming Stengel’s initial boast of Mantle as the next best thing in baseball.

In making their customary journey to the World Series for 1957, Stengel’s New York Yankees ran head-on into the game’s new, and unlikely, next best thing: A skinny, quiet and unassuming 23-year old from Alabama who himself had developed into a one-of-a-kind luminary at the plate.

Without Hank Aaron, who kicked into permanent high gear like Mantle the year before, there’s little chance that the Milwaukee Braves would have toppled the Yankees in the Fall Classic. While Aaron’s teammates managed a collectively mere .183 batting average against Yankees pitching, he picked them up by hitting .393 while belting three home runs, helping to forge an entertaining seven-game Series that ultimately deprived New York City of a baseball champion for the first time in nine years.

Upon moving from Boston in 1953, the Milwaukee Braves instantly transformed from chronic cellar dwellers to hard-luck contenders—always in the hunt, but never able to clear that one last hurdle. They came closest in 1956, blowing a one-game lead going into the season’s final weekend.

The Braves certainly had top-flight talent on both sides of the docket to look like a polished champion. Pitching ace Warren Spahn had already accomplished enough to earn a place in the Hall of Fame—and now, at 36 years of age, he was only starting to get better. Spahn was well complemented in the rotation by fellow starters Bob Buhl and Lew Burdette. Eddie Mathews was a perennial All-Star at third base with prodigious power, already amassing 200 career home runs by age 25; and first baseman Joe Adcock was developing into an equally fearsome force, prone to sudden bursts of slugging that kept opposing pitchers on edge.

Then there was Hank Aaron.

Born and raised in Mobile—a hotbed of future African-American ballplayers that would include Billy Williams and Willie McCovey—Aaron was taken into the Indianapolis Clowns, who in the dying last days of the Negro Leagues began to self-promote themselves as a baseball sideshow not unlike the Harlem Globetrotters. Aaron’s mild-mannered personality hardly fit in with the Clowns’ bag of tricks, but his talent was an attraction for major league scouts who began to focus on his potential. Aaron would only get better when one of the scouts suggested he stop holding the bat cross-handed.

After signing with the Braves, Aaron was assigned to the team’s Class A affiliate at Jacksonville, helping to integrate the South Atlantic “Sally” League with four other black players. There Aaron experienced what Jackie Robinson went through, and worse. Playing in a league fully ingrained in the Deep South, Aaron was constantly rained upon with the vicious verbal abuse, hate mail and death threats—and no one on the outside paid attention, having been mostly satisfied with progress in the big leagues. Aaron, like Robinson before him, won the fans over in the only two ways he could: By not fighting back, and by playing great baseball. He batted .362 with 22 home runs and was named the Sally’s Most Valuable Player.

BTW: Aaron picked the Braves over the New York Giants because he felt he had a better chance of playing every day.

The Fans That Made Milwaukee Famous

Averaging over two million a year in attendance, the Braves easily outpaced other major league teams at the gate over their first five years in Milwaukee.

Aaron came to the Braves’ camp in 1953 and lucked into a starting job when Bobby Thomson broke an ankle in spring training. At age 20, Aaron batted .280 with 13 homers before breaking his own ankle late in the year. More importantly, Aaron found a far more tranquil setting in Milwaukee, an epitome of wholesome 1950s Americana that seemed light years away from the racially divisive South. As his star grew, Aaron was embraced by a rabid fan base that annually packed County Stadium with over two million fans, an eye-popping number for the time.

Aaron improved significantly as a sophomore, batting .314 with 27 homers and 106 runs batted in while making the first of 21 consecutive All-Star appearances. In 1956, he won the National League batting title with a .328 average, adding 26 more homers.

Yet he was still warming up to become the next big thing.

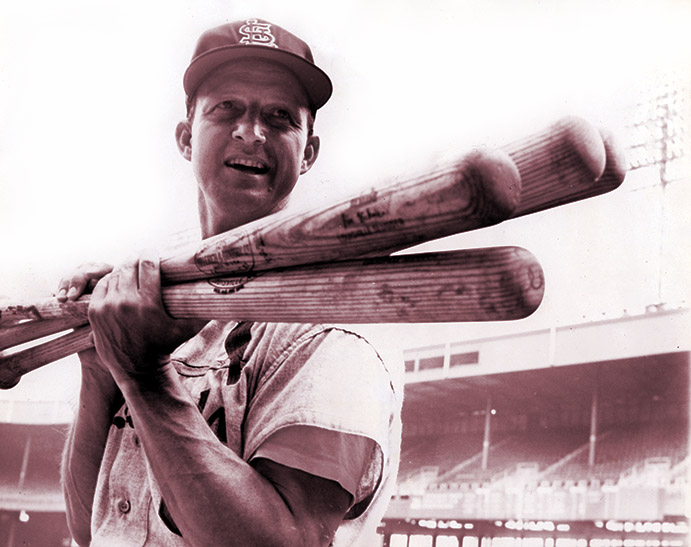

In 1957, Aaron and the Braves once again found themselves on the tails of the league leader—in this case, the St. Louis Cardinals, fired up by a 36-year-old Stan Musial on the way to winning his last of seven batting titles at .351. But Milwaukee got a double dose of good news to begin August, winning 10 in a row while the Cardinals lost nine straight. Catapulted into the open, the Braves quickly secured a healthy lead and overcame an attempted St. Louis rebound in September by winning another eight in a row—with win number seven clinching the pennant thanks to a game-winning, 11th-inning home run by Aaron against the Cardinals at County Stadium.

Aaron’s first monster year secured him the league MVP award, matching his uniform number with 44 home runs while knocking in 132 runs; three other NL batters kept Aaron from winning the triple crown by hitting higher than his .322 mark.

BTW: Aaron wore number 5 in his rookie year, but switched to 44 in 1955.

In a year where aging superstars forged a second wind, Stan Musial gave himself renewed baseball life at age 36—garnering his seventh and final batting title while helping the St. Louis Cardinals battle out with Milwaukee for the National League pennant. (The Rucker Archive)

The other usual suspects in Milwaukee contributed to the Braves’ pennant, including Spahn with 21 wins and Mathews with 32 home runs. But just as crucial were a number of midseason roster additions. After an on-field collision between outfielder Bill Bruton and second baseman Felix Mantilla—knocking Bruton out for the year, Mantilla for a month—the Braves traded for veteran Red Schoendienst, who set a spark by batting .310 and playing excellent defense while Mantilla stayed on the bench, even after he returned to good health. In Bruton’s place, the Braves brought up from the minors Bob Hazle, who would become one of baseball’s most famous flashes in the pan. In 41 games, the rookie batted .403 with seven homers and 27 RBIs, a half-year wonder of statistics in a career that would quickly cool off and end by 1958.

The continued graying of the Brooklyn Dodgers finally took its toll on the defending two-time NL champions, but so did a sharp drop-off from pitcher Don Newcombe (battling alcoholism) and off-field distractions over growing noise that the franchise was looking to move west—not to New Jersey, but to California. The Dodgers finished third, 11 games back.

The other defending league champs, the New York Yankees, made some unwanted news of their own early in the year. When Yankees players went to New York’s popular Copacabana club to celebrate Billy Martin’s 29th birthday in May, a bowling team at the next table began heckling the man on stage—singer Sammy Davis, Jr.—infuriating the Yankee Rat Pack led by Martin, Mickey Mantle and Whitey Ford into an all-out brawl with the bowlers.

Though outfielder Hank Bauer was considered the main combatant against the bowlers (who sued him), Yankees general manager George Weiss tagged the blame on Martin, who he thought had become a bad influence on the rest of the team. And when Martin engaged in a vicious scuffle a month later at Chicago against Larry Doby, Weiss said enough and gave Martin the classic Yankee demotion—a trade to the Kansas City A’s, a team that many believed was acting as the New York’s unofficial top farm club.

Short-term, Martin’s departure helped the Yankees—who were just embarking on a stretch where they would win 24 of 28 games to overtake the Chicago White Sox, American League leaders for much of the first two months. Long-term, the trade also cleared the way for a young, talented—and far more clean-cut—prospect, Bobby Richardson, to take Martin’s spot at second base.

Refocusing on baseball over the night life, the Yankees coasted through the summer to finish eight games over the White Sox, now being managed by former Cleveland skipper Al Lopez—who despite the change of address still found himself in second place. Mickey Mantle continued as the team’s dominant force; batting .365, he would have won his second straight batting title had it not been for 39-year-old Ted Williams’ phenomenal .388 effort. On the mound, New York pitching was collectively the best in baseball, as Casey Stengel successfully played his platooning game with a staff that included seven different hurlers starting at least 11 games each. Former Athletic Bobby Shantz (2.45), Tom Sturdivant (2.54) and Bob Turley (2.71) were first, second and fourth, respectively, in the AL ERA race.

BTW: Mantle’s 34 homers and 94 RBIs were down from his triple crown numbers of the year before, as opponents began to pitch him more carefully—evidenced by a major league-high 146 walks.

But it was a former Yankees prospect, released from New York six years earlier, who would team with Hank Aaron to deny the Bronx Bombers a chance at a second straight World Series triumph.

While Aaron’s hitting was doing the damage for Milwaukee at the plate, it was 30-year-old right-hander Lew Burdette who took the mound and frustrated the fastball-hungry Yankee bats with his assortment of junkball specialties. In Game Two, Burdette allowed two early runs but settled in and went the distance for a 4-2 win. In Game Five, he won a pitching duel over Whitey Ford, tossing a seven-hit, 1-0 shutout. And in the deciding seventh game, Burdette was paired against Don Larsen—making his first Series start since his perfect game of a year earlier—and again shut down the Yankees on seven hits, while Larsen was gone after allowing four early runs in a 5-0 triumph that gave the City of Milwaukee its first and only baseball championship to date.

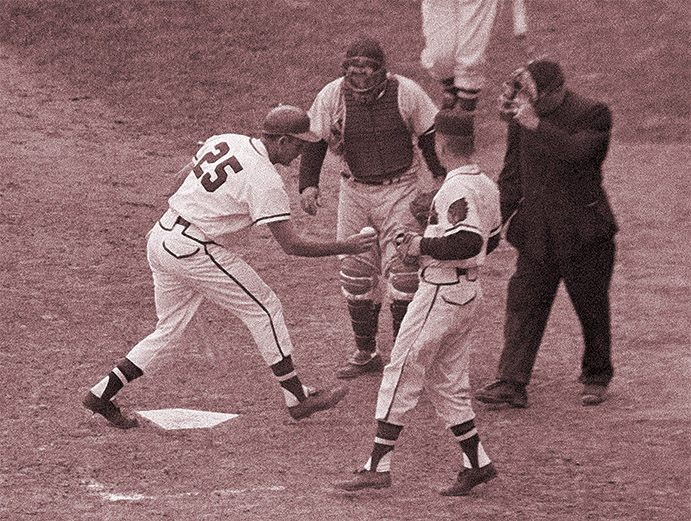

The World Series turns in Milwaukee’s favor when the Braves’ Nippy Jones convinces umpire Augie Donatelli that he was hit on the foot by showing that the ball has shoe polish on it. (Associated Press)

Though none of Aaron’s Series-leading 11 hits came at dramatic stages or with any walk-off theatrics, his three-run blast early in Game Four proved pivotal in the later stages, setting up an extra-inning affair that would end in controversy.

Trailing 5-4 to start the bottom of the 10th, Milwaukee leadoff hitter Nippy Jones was hit on the foot with a Bob Grim pitch that continued to the backstop—but umpire Augie Donatelli ruled that the ball had made no contact with Jones. Pleading his case, Jones introduced the ball—showing a streak of shoe polish from his cleat—as evidence. Donatelli agreed and gave Jones the base. Pinch-running for Jones as the tying run, Felix Mantilla scored two batters later on a double by Johnny Logan, and Eddie Mathews connected on a two-run blast to win the game. Jones’ shoe polish—and Aaron’s home run before it—kept the Braves from dropping into a three-games-to-one hole.

Life was good for Hank Aaron. He proved to the few remaining doubters that he had arrived as a superstar of the highest order, had won his first and only MVP award, and won his first and only World Series for a city he was delighted to call home.

For all of his later achievements, some drenched with the sad specter of racist overtones, 1957 would remain his happiest year.

Forward to 1958: And Now, From Coast to Coast The Dodgers and Giants break the hearts of New Yorkers everywhere and head west to California.

Forward to 1958: And Now, From Coast to Coast The Dodgers and Giants break the hearts of New Yorkers everywhere and head west to California.

Back to 1956: A Perfect Revenge The New York Yankees’ Don Larsen earns immortality in a day and denies the Brooklyn Dodgers their second straight title.

Back to 1956: A Perfect Revenge The New York Yankees’ Don Larsen earns immortality in a day and denies the Brooklyn Dodgers their second straight title.

1957 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1957 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1957 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1957 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1950s: A Monopoly of Success Though described as a golden age for baseball, most major league teams find themselves struggling—unless you’re in New York City, where the Yankees, Dodgers and Giants hog the World Series podium from 1950-56. But as the decade winds to a close, the euphoria of Big Apple baseball will rot overnight.

The 1950s: A Monopoly of Success Though described as a golden age for baseball, most major league teams find themselves struggling—unless you’re in New York City, where the Yankees, Dodgers and Giants hog the World Series podium from 1950-56. But as the decade winds to a close, the euphoria of Big Apple baseball will rot overnight.

At a time when UFOs were all the rage, pitcher Ed Mayer recounts a close encounter in the minors. Seriously.

At a time when UFOs were all the rage, pitcher Ed Mayer recounts a close encounter in the minors. Seriously.