THE YEARLY READER

1947: The Arrival of Jackie Robinson

After enduring a lifetime of stubborn alienation from organized baseball, African-Americans finally get a chance when Jackie Robinson signs with the Brooklyn Dodgers—but it proves to be anything but a red-carpet welcome.

To opponents set in their segregationist ways, Jackie Robinson was a constant prime target once he broke baseball’s longstanding color barrier. (The Rucker Archive)

When Brooklyn Dodgers president Branch Rickey first told Jackie Robinson that he would have to wear an “armor of humility” to survive his initial test of major league experience, Robinson knew he would need it to ward off the racial intolerance and abuse that was certain to come from fans and players. But he never expected to see it coming from a policeman in DeLand, Florida, who stormed the field to stop a spring training game involving a Dodgers team with Robinson in the lineup.

It was a long and tormenting road for Jack Roosevelt Robinson from the time Rickey signed him in October of 1945 through his first season as a Dodger two years later. But that journey would be of major historical importance, transcending the simple borders of the baseball world. Robinson’s breaking of the game’s color barrier would become an early, defining moment in the struggle of African-Americans to find equality and acceptance within their own country.

No blacks had been able to perform in a major league uniform since Moses Fleetwood Walker was chased off the field in 1884 as protests to segregate grew louder from white players and executives. The no-blacks policy, written or unwritten, would remain the status quo for six decades.

While many white major leaguers paid high compliments to the talent level of the Negro Leagues, most others were polluted with racial hatred during the early portion of the 20th Century. Ty Cobb, often described as openly racist, disparaged blacks as “darkies” and insisted that their place in baseball was reserved as “clubhouse help.” Other superstars such as Rogers Hornsby and Tris Speaker were reportedly members of the Ku Klux Klan during the 1920s.

As baseball entered the 1940s, the pressure to integrate was turned up. Black activists confronted major league executives to remove the racial barrier—and some of them were listening. The Pittsburgh Pirates gave strong consideration to signing Josh Gibson, the Negro Leagues’ answer to Babe Ruth, while Bill Veeck claimed he wanted to buy the Philadelphia Phillies and fill the roster with African-Americans.

All attempts at desegregation hit the same roadblock: Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis. Though he claimed there was nothing etched in stone disbarring blacks from the majors, his stubborn discouragement upon owners thinking about integration amounted to a firmly cemented, yet unwritten, code.

In November of 1944, Landis died.

Though Landis had done much to save and then maintain the sport’s stature during his 23-year tenure, his passing elicited sighs of relief from those whom shared long-exhaustive hopes of integrating the game.

For years, Branch Rickey had strained publicly to fend off the pleas of those wanting integration. But he held his own private, patient agenda to tap into the Negro League market—and in the wake of Landis’ death, Rickey knew the time was now. He wasn’t necessarily after the most talented Negro Leaguer, but the one who best could handle the intense pressure and intolerance Rickey knew was sure to follow as a result of that player’s presence.

Jackie Robinson looked every bit the man to play the part. Born in Georgia in 1919, he had to grow up fast when his father deserted the family. Rather than wilt under the circumstances, Robinson hardened through self-reliance. Moving with his mother west to Pasadena, California, he became athletically gifted enough to letter in four sports at UCLA. During World War II, Robinson enlisted in the army—and asserted his resolve against racial prejudice when he refused to sit in the back of a military bus. A court martial against him ensued—for which he was acquitted.

When Robinson’s talent and attitude captured the eye of Dodgers scout Clyde Sukeforth—who bought into Rickey’s cover story that the team was looking for talent to help organize a new Negro league—Rickey knew he had his man.

Nobody gave Jackie Robinson more racist-loaded hell on the field than Philadelphia Phillies manager Ben Chapman; when he realized he was in the minority opinion, he played nice and posed with Robinson in an attempt to rehabilitate his reputation. (The Rucker Archive)

There was little doubt of Robinson’s ability to play in the majors, and in the spring of 1947 the Dodgers officially added him to the parent roster. But Robinson was hardly home free, facing wave after wave of race-based resistance.

First, he had to survive the major league owners. In response to Rickey’s announcement that Robinson was joining the Dodgers, the other 15 owners voted against the move, officially making the majors a whites-only society after years of posturing to the contrary. But Rickey had a lone yet powerful ally who overruled the owners: Baseball’s new commissioner, Happy Chandler. Landis’ replacement sided with Rickey because, among other reasons, he said doing otherwise would have made it difficult to explain his decision when he met his “maker.”

Next, Robinson had to survive his own teammates. Alabama-born Dixie Walker, a Brooklyn fan favorite, began circulating a petition among the players to have Robinson removed from the roster. Some of the southern-born Dodgers signed on, but when manager Leo Durocher heard about the movement, he lit into Walker in front of the team. The petition died and Walker asked to be traded; the Dodgers eventually obliged.

BTW: Walker, the Dodgers’ most productive hitter through the mid-1940s, would finish out 1947 in Brooklyn before being dealt to Pittsburgh.

Having defeated the owners and having won his teammates over, Robinson’s last hurdle toward major league acceptance—gaining the respect of opposing players—would be the most vicious of all.

The Chicago Cubs privately voted to boycott playing against Robinson and the Dodgers, but went out on the field anyway—knocking Robinson down whenever he came to the plate. The St. Louis Cardinals made a bigger splash when the media got word that they were ready to oppose playing against Brooklyn. True or not—Cardinals players denied it—the strike threat forced National League president Ford Frick to throw down the gauntlet, announcing that any player who refused to play against Robinson would receive a lifetime ban from the game.

Teams that chose not to boycott Robinson gave him serious hell. The worst offenders were the Phillies and their manager, Ben Chapman, a Tennessee manager who led his players on a mortifying, non-stop tirade of racial slurs. As if that wasn’t enough, some Phillies pantomimed as snipers, aiming their bats at Robinson as if they were rifles. It all reached near traumatizing proportions for Robinson, and it stunned even Dodgers players who were borderline on whether he should belong or not.

In Cincinnati—where more baiting, epithets and death threats were all being aimed at Robinson—the Dodgers had seen enough. Kentucky-born shortstop Pee Wee Reese, an emerging Brooklyn star on his own, finally answered the continued heckling by going over to Robinson, putting an arm around his shoulder, and loudly announcing to the Reds: “This is the guy, and we’re gonna win with him.”

And win the Dodgers did with Robinson, though it understandably took awhile for Jackie to warm up. He slumped at the start under the intense spotlight, going hitless in 20 straight at-bats at one point. But the 28-year-old rookie first baseman got into a higher gear by midseason, piecing together a 21-game hitting streak and batting near .300 at the All-Star break.

The addition of Robinson—and the brutal reception he received from the rest of the league—simply galvanized the Dodgers into a tighter and stronger unit. Thrusting into first place in July thanks to a 13-game win streak, they eventually outlasted the defending world champion Cardinals by five games. Statistically, there were no standouts in the lineup—just eight solid regulars doing their job well. The big surprise on the Brooklyn roster came from right-handed pitcher Ralph Branca, who matched his age with 21 wins and a 2.67 earned run average, both team bests.

Then there was Robinson. He led the NL with 29 steals, placed second with 125 runs scored, and with Reese co-led the Dodgers with 12 home runs. He finished fifth in the league’s Most Valuable Player voting.

Robinson’s outstanding debut loosened the chains elsewhere as more black players were allowed to filter onto major league rosters. In early July it was Bill Veeck, now the owner at Cleveland, who brought Larry Doby to the Indians as the first black American Leaguer. A few weeks later, the St. Louis Browns signed two African-Americans, Hank Thompson and Willard Brown. The Dodgers themselves added pitcher Dan Bankhead who, although a washout on the mound, hit a home run in his first at-bat—the first major league pitcher of any color to do so.

It had been four years since the New York Yankees had reached the World Series—a dustbowl of a drought by their standards. But they returned to the top of the American League standings in 1947, in the interim having changed ownership, front office personnel and manager.

Acquisitions and trades did particular wonders for the Yankees under former Washington skipper Bucky Harris. In a deal that was good for both ballclubs, pitcher Allie Reynolds came over from the Indians for infielder Joe Gordon and led the Yankees with 19 victories. First baseman George McQuinn, whose career seemed to do a quick fadeout the year before with the Philadelphia A’s, came back to life by hitting .304 for the Yankees at age 38. And at midseason, Bobo Newsom was acquired from Washington because, if for anything else, he had pitched for almost every other team and felt it was his due to finally play at New York. The 40-year old made much of the effort, winning seven of 12 decisions with a 2.80 ERA.

Bolstered by a lineup led by outfielders Joe DiMaggio and Tommy Henrich, the Yankees won a club-record 19 straight games in July and blasted their way to a 12-game finish over the Detroit Tigers. The defending AL champion Boston Red Sox, 14 games back, suffered from a partial collapse within their starting rotation and finished third.

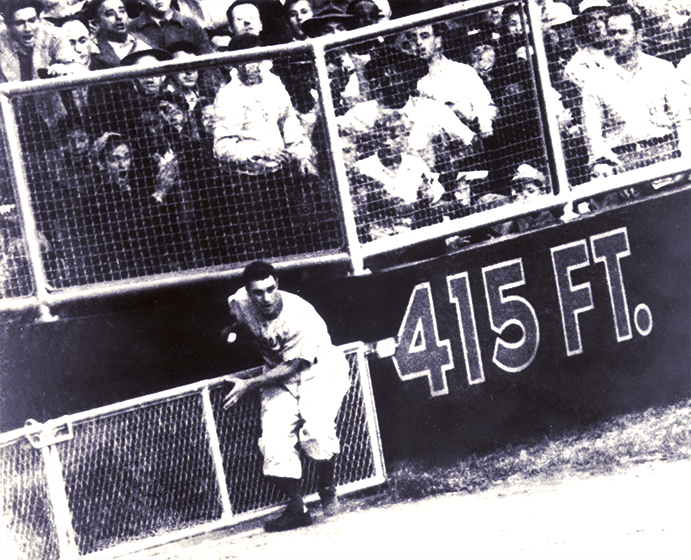

In the last major league game he would play, the Dodgers’ Al Gionfriddo makes a terrific catch against the Yankee Stadium fence to rob Joe DiMaggio of at least a two-run double in Game Six of the World Series. The Dodgers won the game by two; they lost the series in seven. (The Rucker Archive)

Pairing off against Robinson and the Dodgers in the World Series, the Yankees won the first two games before events got really interesting.

After Brooklyn won a wild Game Three, 9-8, the Dodgers managed just one hit in Game Four—a two-out, ninth inning double by Cookie Lavagetto off Yankee pitcher Bill Bevens, who had walked 10 batters, including the two on base who scored on the hit that gave Brooklyn a 3-2 victory. The Dodgers then forced a seventh game thanks to part-time outfielder Al Gionfriddo, who saved an 8-6 Brooklyn win in Game Six by making an outstanding catch of a Joe DiMaggio drive, leaping in front of and bouncing off the Yankee Stadium left field wall. DiMaggio, in a rare outburst of on-field emotion, responded to the catch by taking an angry kick at the infield dirt.

BTW: For Bevens, Gionfriddo and Lavagetto, the 1947 World Series would be the last time they would appear in a major league uniform.

By Game Seven, the Dodgers ran out of surprises. The Yankees tamed Brooklyn, 5-2, and won their first championship in four years.

Jackie Robinson had a nondescript showing in his first Fall Classic, batting .259 with a pair of doubles and two stolen bases. But there would be much written about the prescript to and experiences throughout Robinson’s first major league campaign. His armor of humility remained intact, all while winning over the hearts of millions. A 1947 poll named Robinson the second most admirable American (after actor-singer Bing Crosby) and he was given the first Rookie of the Year Award by the Baseball Writers’ Association of America, as well as a similar honor by The Sporting News—a historically conservative tome which previously had held a stubborn, suspect opinion of Robinson’s abilities, while giving softball treatment in print to Dixie Walker, Ben Chapman and the others who engaged in some of the first-year Dodger’s ugliest controversies.

Robinson’s significance went beyond baseball, igniting a generation of Americans who knew racial integration was inevitable. It would take many painful years to get there, but baseball took warm comfort that, for a change, it was ahead of everyone else.

Forward to 1948: The Greatest Show in Cleveland Bill Veeck, the maverick owner of the Cleveland Indians, brings ’em through the gates with memorable attractions on and off the field.

Forward to 1948: The Greatest Show in Cleveland Bill Veeck, the maverick owner of the Cleveland Indians, brings ’em through the gates with memorable attractions on and off the field.

Back to 1946: It’s Good to be Home The players are back and so are the fans, as attendance booms in baseball’s first postwar campaign.

Back to 1946: It’s Good to be Home The players are back and so are the fans, as attendance booms in baseball’s first postwar campaign.

1947 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1947 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1947 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1947 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1940s: Of Rations and Spoils The return to a healthy economy and the breaking of the color barrier helps baseball reach an explosive new level of popularity—but not before enduring with America the hardship and sacrifice of World War II.

The 1940s: Of Rations and Spoils The return to a healthy economy and the breaking of the color barrier helps baseball reach an explosive new level of popularity—but not before enduring with America the hardship and sacrifice of World War II.

Wally Westlake recalls Jackie Robinson, and his experience being the first white player to be hit by a black pitcher.

Wally Westlake recalls Jackie Robinson, and his experience being the first white player to be hit by a black pitcher.