THE YEARLY READER

1933: Making Little Napoleon Proud

Dying of prostate cancer and recently retired after 30 years of managing the New York Giants, John McGraw watches as replacement Bill Terry resuscitates the team to a World Series triumph over the Washington Senators.

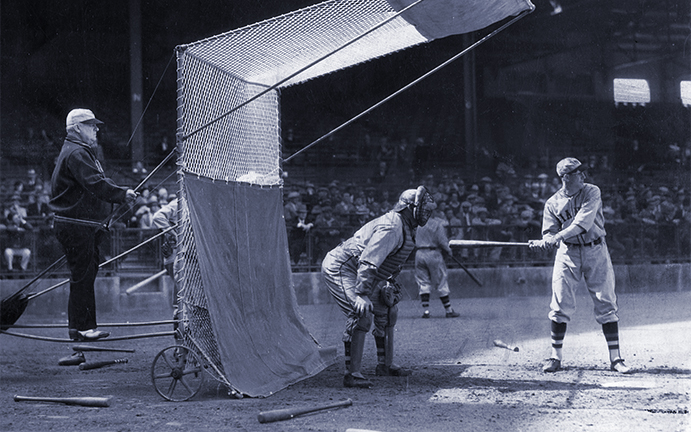

Even at the tail end of his long, remarkable reign as the New York Giants’ manager, John McGraw remained dedicated to enriching the immense talent he had assembled, as shown here with Travis Jackson shortly before handing the reins over to Bill Terry. (The Rucker Archive)

Bill Terry was not on speaking terms with John McGraw when the New York Giants’ first baseman was called into the legendary manager’s office early in the 1932 season.

Terry had refused to speak to McGraw after his salary was cut 25%—despite batting .349 the previous year. McGraw’s justification for the cut? Terry’s 1931 average dropped 52 points from his 1930 mark of .401. Never mind that the ball was deader in 1931 and everyone’s average seemed to drop precipitously; the front office’s spin ruled.

But Terry remained speechless—although for a different reason—with what McGraw was ready to tell him.

McGraw was quitting the game, and was offering Terry his job.

This was big news, huge. McGraw had dominated the Giants, the National League and the headlines during the 30 years he ran the team at the Polo Grounds. Though his deteriorating health had eroded the element of surprise, press coverage of McGraw’s retirement superseded the other big baseball news of the day: A four-homer day by the Yankees’ Lou Gehrig, the first such achievement in the 20th Century.

While bad health was a major factor in McGraw’s decision to leave, so was his growing failure to understand the modern ballplayer. In his early years he had been a wiry, determined autocrat who did it his way or else; his collection of rough-and-tumble types related well to him—and vice versa—winning 10 NL pennants over his first 22 years at New York.

But the professional baseball player of the 1930s was more sophisticated and educated than ever—and therefore, more annoyed than intimidated by McGraw’s Stalinist disposition. Older, sicker and more portly, McGraw had also developed a healthy touch of senility; catcher Bob O’Farrell, who played briefly for McGraw in the late 1920s, simply remembered him as “grouchy.” More and more, McGraw took credit for the wins while blaming others for the losses. Though he maintained a good eye for talent and kept the team competitive, he hadn’t broken through to a pennant in seven years—a heady drought by his standards.

Terry was definitely representative of the new breed of player. Whereas McGraw in the old days plucked his players out of low-paying forms of drudgery such as coal mining, Terry had to be coaxed out of the front office of an oil company. But Terry was talented all the same, a consistent .300-plus hitter and the last National Leaguer to hit .400, in 1930.

BTW: Terry had collected nearly 1,000 hits between 1929-32, entering his first full year as player-manager.

Nicknamed Memphis Bill after the town where McGraw grabbed him from, Terry took over as manager 40 games into the 1932 season and could only settle for sixth place. But in the process he smoothed out some bumps. Fired was McGraw’s trainer, for whom Terry suspected was Little Napoleon’s eyes and ears. Another problem was star third baseman Fred Lindstrom. Although he was glad to see McGraw go, Lindstrom wanted himself, not Terry, in the pilot seat. The resulting friction gave Terry no choice but to send the nine-year Giant veteran off to Pittsburgh following the season.

Entering 1933, the remaining Giants players had a pretty good bead on what to expect in Terry’s managerial style. It was a conservative strategy of mind over batter, emphasizing pitching, defense and winning the close ones, rather than crossing his fingers and hoping to outslug the opponent as employed by most major league teams since 1920. McGraw must have been impressed; it was retro deadball era strategies at work.

Making a humble prediction to the press corps that his Giants could finish as high as third, Terry found himself right there by Memorial Day, in the thick of a tight NL pennant race. But Terry had played little to that point due to a broken wrist, and knew his return coupled with a move elsewhere in the roster could bolster the Giants’ odds. So he sent Sam Leslie—who had filled in for Terry at first base—to the Phillies for veteran outfielder Lefty O’Doul, who would slam nine home runs while batting .306 in half a season’s work for the Giants.

A Polo Grounds doubleheader against the contending St. Louis Cardinals in early July proved to the rest of the NL that Terry’s Giants—and especially his pitching staff—were for real. In the first game, screwball pitcher Carl Hubbell forever upgraded his reputation from solid to spectacular, blanking the Cardinals 1-0 in an exhaustive 18-inning battle. Young Roy Parmelee then outdueled an even younger Dizzy Dean in the nightcap by the same score in nine innings. The 27 frames of shutout baseball were the most ever thrown at a team in a doubleheader, and it sent the Cardinals reeling into a slump; by the time they recovered, they, along with the rest of the league, had lost crucial ground to the Giants.

BTW: Hubbell and Parmelee combined to strike out 25 and walk just one during the twinbill.

Terry’s starting rotation came out of nowhere to compensate for an average offense and gave the Giants their first pennant in nine years. At 30 years of age, Hubbell’s first remarkable year consisted of 23 wins (including 10 shutouts) and a major league-leading 1.66 earned run average—the lowest seen in either league since the deadball era’s last breath of life in 1919. Parmelee and Hal Schumacher, both entering the year as unknowns with only nine combined career wins, grouped up for a 32-20 record in 1933; Schumacher’s 2.16 ERA was third best in the league.

Over in the American League, the powerhouses fell vacant. At New York, the defending champion Yankees witnessed a remission in their pitching, while Babe Ruth—though still potent at 38—was gradually showing he was past his prime. Meanwhile, for Connie Mack and his Philadelphia A’s, it was about to become 1915 redux. As he did then, the Tall Tactician saw the financial writing on the wall—he had lost a ton of money on stocks through the deepening depression—and believed the empire of talent he had built over the last 10 years had run its course in front of dwindling, more complacent Shibe Park crowds.

So Mack tore apart his second dynasty, more slowly but just as surely. Before the season he dealt away Al Simmons, Mule Haas and Jimmie Dykes to the Chicago White Sox for $100,000. Then, on a single day in December after the season, he sent all-world pitcher Lefty Grove, Rube Walberg and Max Bishop to the Boston Red Sox for $125,000; catcher Mickey Cochrane to the Detroit Tigers for $100,000; and George Earnshaw to the White Sox for $20,000. At 71, Mack thought of retiring but stayed put for 17 more years over a franchise that would become weakened second-division meals for the rest of the league.

Slipping through the aging cracks of fallen empires were the Washington Senators, who with 99 wins enjoyed the most proficient AL campaign they would ever realize in the Nation’s Capitol.

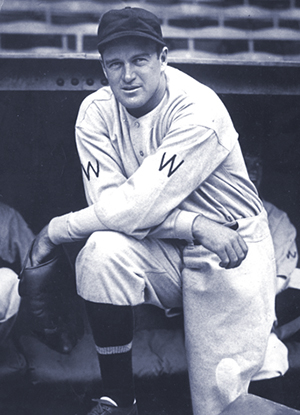

Joe Cronin was the second Washington manager in less than a decade to take the job while still in his 20s—and like the first, Bucky Harris, took the Senators to the World Series in his first year at the helm. (The Rucker Archive)

As the Senators’ second “boy wonder,” the 26-year-old Cronin repeated the path of Bucky Harris nine years earlier and took the AL pennant in his first year of managing, instructing a group of everyday regulars and starting pitchers all older than himself. The Washington veterans included two former batting champions (Heinie Manush and Goose Goslin), a future batting champ (Buddy Myer) and an active workhorse on the mound in Alvin “General” Crowder, who started 35 games, relieved in 17 others and, for the second year in a row, led the AL in victories with 24.

Cronin’s Senators also let it be known that they were ready to fight. In an early season contest at New York, the team rallied and responded with words and fists, adding to an ugly situation where Yankees baserunner Ben Chapman—well known for his insensitivities toward mankind—made a vicious slide into Senators second baseman Myer, who was Jewish. Myer, Chapman and 22-game winning Senator pitcher Earl Whitehill were all suspended five days each for their central roles in the ensuing brawl, which nearly tuned into a full-scale riot at Yankee Stadium.

BTW: Chapman’s name would be infamously linked with Jackie Robinson 14 years later, when as manager of the Philadelphia Phillies he led a profane onslaught of racist remarks at Robinson while playing against him.

First in War, First in Peace, Second in the American League

Most casual baseball fans think of the Washington Senators as a long-running American League joke. But there was nothing funny for opponents of the Senators from 1912-33, which as shown below represented a period of baseball in the Nation’s Capitol eclipsed in performance only by the emergence of the mighty Yankees.

A World Series rematch between the Giants and Senators lacked the suspense, drama—and wayward pebbles—of the 1924 original.

With two player-managers strategizing against one another, it was superior Giants pitching that would ultimately neutralize the solid Senators offense. Washington could muster only five earned runs off New York hurlers through a five-game Series loss, ending with two extra-inning defeats at Griffith Stadium. Carl Hubbell, in particular, held the Senators down tight; he allowed only three runs (all unearned) on 13 hits over 20 innings, winning both of his starts—including an 11-inning, 2-1 Game Four nail-biter.

Perhaps the most memorable game of the season was the one that didn’t count in the standings: The inaugural All-Star Game at Chicago’s Comiskey Park.

Games of this sort had been played before, but they were mostly benefit contests, often matching up a group of stars against a regular team. But Chicago Tribune sports editor Arch Ward thought up something more novel; to hold an exhibition of the best players in both leagues to compete against one another. And if the fans weren’t excited enough of the idea of seeing the best of the best, they would be the ones granted the power to select the players. The All-Star Game was a great concept, a heavily hyped event, and an instant hit.

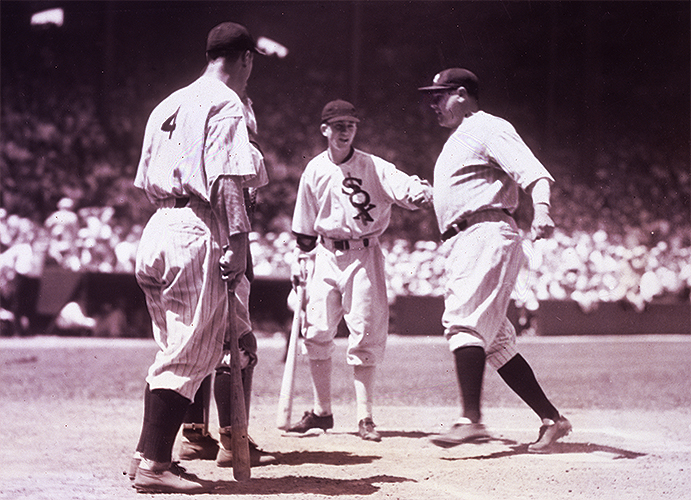

Babe Ruth crosses home plate after hitting the first home run in All-Star Game history at the inaugural event at Chicago’s Comiskey Park. (The Rucker Archive)

On a hot July afternoon in Chicago, a sellout crowd of over 47,000 paid a top ticket price of $1.65 to see a who’s who of baseball legends: Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Al Simmons, Lefty Grove, Jimmie Foxx, Paul Waner, Carl Hubbell, Frankie Frisch, Chuck Klein—the list of greats went on and on.

The American League scored early and held on to win the initial battle, 4-2. All too appropriately, Babe Ruth hit the first home run in All-Star Game history; all too surprisingly, Yankees pitcher Lefty Gomez knocked in the first run. Gomez more suitably emerged as the winning pitcher, while Grove pitched the final three innings to collect the save; the Cardinals’ Wild Bill Hallahan was tagged with the loss for the National League.

Originally planned as a one-time event to coincide with a world’s fair being held in Chicago, baseball owners decided to continue this “Game of the Century” as an annual event, to be played every July at a different ballpark across the majors. And thus, the “Mid-Summer Classic” would become as important an addition to the baseball calendar as Opening Day and the World Series.

More than a year after he stepped down, John McGraw was brought back to Comiskey Park to manage the NL all-stars. Tired and weakened by his condition, he basically came as a figurehead and sat quietly in the dugout during the game, while it was Bill Terry— the man he hand-picked as his replacement in New York—who appeared to do most of the directing.

Little Napoleon had lived just long enough to see that his team carry on well without him. He was on the podium at New York City to help celebrate the Giants’ NL pennant, attended the World Series with his wife Blanche, and threw a party for the team when they returned triumphant from Washington.

Four months later, at the age of 60, John Joseph McGraw lost his battle with cancer and died in New Rochelle, New York.

Forward to 1934: Dizzy, Daffy and Ducky The Cardinals’ Gashouse Gang goes into full bully mode behind the dazzling Dean brothers.

Forward to 1934: Dizzy, Daffy and Ducky The Cardinals’ Gashouse Gang goes into full bully mode behind the dazzling Dean brothers.

Back to 1932: The So-Called Shot Babe Ruth’s historic and highly debated gesture gives a hostile World Series its flashpoint.

Back to 1932: The So-Called Shot Babe Ruth’s historic and highly debated gesture gives a hostile World Series its flashpoint.

1933 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1933 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1933 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1933 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1930s: Dog Days of the Depression The majors take a hit from the Great Depression as both attendance and bravado are on the wane—until newborn icons Joe DiMaggio and Ted Williams emerge to rejuvenate the game’s passion for the fans.

The 1930s: Dog Days of the Depression The majors take a hit from the Great Depression as both attendance and bravado are on the wane—until newborn icons Joe DiMaggio and Ted Williams emerge to rejuvenate the game’s passion for the fans.