THE YEARLY READER

1929: Running on Ehmke

Philadelphia A’s manager Connie Mack throws a curve at the Chicago Cubs by starting seldom-used pitcher Howard Ehmke in the first game of the World Series, launching the A’s on a five-game triumph back to baseball’s pinnacle.

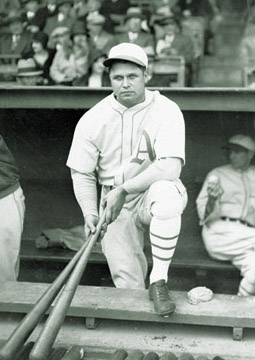

Imcomporable ace Lefty Grove (center)? Nah. George Earnshaw (right), owner of a 24-8 record? Nope. The Philadelphia A’s instead placed their World Series hopes on fading, aging junkballer Howard Ehmke (left). (The Rucker Archive/Chicago Historical Society)

To believe Connie Mack’s version of events, the following happened just weeks before his Philadelphia Athletics entered the World Series:

Washed-up pitcher is called into Mack’s office, is informed of his release; pitcher pleads with Mack that he has one good game left in his arm, begs to start the first game of the World Series—and gets it.

Cinderella would have been envious.

Yet veteran junkball pitcher Howard Ehmke dodged the junkpile, donned the proverbial crystal slippers and made good on his promise, completely quieting the powerful Chicago Cubs in one of the Fall Classic’s most memorable pitching performances. All before midnight.

Some believed the Tall Tactician’s story to be a tall tale, more inclined to think that Ehmke entered the office assuming the worst and, frightened, made his case to Mack—all before the A’s manager had a chance to tell Ehmke what he’d been called in for: To take the remaining weeks of the regular season off, scout the Cubs—the runaway National League champions—and prepare to face them in Game One.

After an initial tasting of major league ball in the ill-fated Federal League, the young Ehmke was taken in by the Detroit Tigers in 1916 and soon became one of their more dependable, if not successful, starting pitchers. After a trade to the Boston Red Sox—at the time, baseball’s equivalent to banishment in Siberia—Ehmke’s record surprisingly improved. He won 20 games for a 1923 Red Sox team that won only 61, and followed up with 19 more in 1924. But the cellar-dwelling mindset of the Red Sox ultimately caught up to Ehmke; he finished 9-20 in 1925, then was off to another miserable start in 1926 when he was freed to Philadelphia. There his fortunes turned dramatically, halving his earned run average while winning 12 of 16 decisions for the A’s in the second half of the season.

An enormous and intimidating talent at age 21, Jimmie Foxx was given the first base job after a few years of shuffling around the infield and responded with his first great year for the A’s, hitting .354 with 33 home runs. (Chicago Historical Society)

By then the Athletics had long reached high gear and, finally, dethroned the three-time defending champion New York Yankees to second place by a full 18 games with a 104-46 record—the best in franchise history to date, better than any of the great Mack teams of the early 1910s.

The A’s began to see the fruits of their maturing young labor blessed upon them through the mid-1920s. After years of figuring out exactly where to play him, Mack gave 21-year-old Jimmie Foxx a permanent spot at first base—and Foxx responded with impressive development at the plate, batting .354 with 33 home runs and 117 runs batted in. Al Simmons had long since been an anchor in the outfield, but he too reacted (.365 batting average, 34 home runs, an AL-high 157 RBIs) with Foxx as a more menacing influence alongside him in the lineup. As a duo, Foxx and Simmons statistically upstaged Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig—an impressive feat, given that the legendary Yankees slugging duo was still in peak form.

New York’s failure to return to the World Series was underscored by tragedy. Miller Huggins, the team’s diminutive, often humorless manager of 11 years, had always been under constant and intense pressure to win, knowing that anything less than a World Series victory year in and year out would be unsatisfactory. Trying to keep Babe Ruth and the rest of the Yankees completely focused on baseball was tough enough.

Over the past few years, Huggins had begun to show the strain of his job, and toward the end of 1929—his team well behind Philadelphia for the AL pennant—he developed a skin infection that segued into fever and blood poisoning. Hospitalized, Huggins’ condition grew worse until he died a week later at the age of 50. Upon hearing the news at Fenway Park in Boston, the Yankees and Red Sox stopped their game in progress, lined up on the field and held a silent tribute.

BTW: The next day, all scheduled American League games were canceled in memory of Huggins.

The man who would soon take over the reins as Yankees manager was, for now, applying the finishing touches to a champion in Chicago. In four years, Joe McCarthy had turned the Cubs into an emerging force, improving steadily from another average ballclub to a World Series contender.

The 1929 Cubs were a roster of misunderstood castoffs. Pitchers Charlie Root and Pat Malone became quality mainstays on the staff after being given little chance with, respectively, the St. Louis Browns and the New York Giants. The vastly talented Kiki Cuyler was given new life in Chicago after being sentenced to the bench in Pittsburgh by vindictive Pirates manager Donie Bush. Outfielder Riggs Stephenson was a great-hit, no-field part-timer in Cleveland; McCarthy traded for him and went about upgrading both his playing time and defensive skills.

BTW: Stephenson’s biggest handicap was a weak arm caused by a shoulder injury while quarterbacking the University of Alabama football team.

The biggest gift of all on McCarthy’s Cubs was outfielder Hack Wilson. Few players in history had a more curious physique. He stood 5’6” and wore a size six shoe, but between head and toe there was a tightly packed bundle of muscle that seemed primarily invested within his chest and chin. After bouncing around the Giants’ organization through his first three years, Wilson was accidentally left exposed to a winter draft of minor leaguers—thanks to a clerical error in the Giants’ front office—and was snapped up by the Cubs.

BTW: Giants pitching ace Carl Hubbell claimed that manager John McGraw intentionally let Wilson go because of his off-field antics.

Wilson embraced his new home. He was made for Chicago of the Roaring’ Twenties, and vice versa. Local sportswriter Warren Brown’s scouting report on Wilson was simple: A highball hitter on the field and off it. On it, Wilson became a dangerous, perennial home run leader in the National League; off it, he was a common sight on the speakeasy circuit in prohibition times. During one police raid, Wilson reportedly got stuck in a window frame attempting to escape.

A superstar whose personality was in sharp contrast to Wilson completed the Chicago puzzle for 1929. Taciturn and sharply focused on baseball as ever, Rogers Hornsby came from the Boston Braves in a mammoth trade that sent five ballplayers and $250,000 the other way. Cubs owner William Wrigley Jr. orchestrated the deal and could afford to; his team drew over a million fans to refurbished Wrigley Field in each of the last two years, while no other NL club had yet to do it once.

BTW: The Cubs’ 1929 attendance of 1.6 million would remain their highest gate until 1969.

The rediscovered and retooled Cubs demolished the NL competition, wrestling away first-place from the Pirates on July 24 and winning 28 of their next 35 games to pull away with the pennant. Wilson and Hornsby each hit 39 home runs and combined for 308 RBIs. Cuyler was let loose and batted .360 while stealing a league-high 43 bases. Stephenson’s .362 average, 17 homers and 110 RBIs justified the Cubs’ tolerance for his frail defense. On the mound, Malone and Root combined to win 41 games and lose 16; right-hander Guy Bush won 18 himself and saved eight others, while losing only seven.

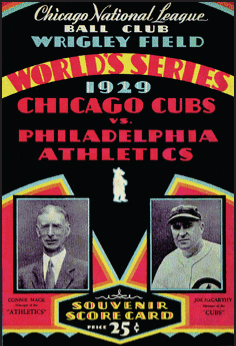

Two of the game’s legendary managers, Connie Mack and Joe McCarthy, are featured in this classy art deco cover for the 1929 World Series program.

Scouting from the stands, Howard Ehmke watched this devastating group of hitters and began to understand why Connie Mack had thought of him for the World Series opener: The Cubs’ batting order was exclusively right-handed save for first baseman Charlie Grimm, a relative non-factor in this lineup. While Philadelphia left-handers Lefty Grove, Rube Walberg and right-handed 24-game winner George Earnshaw all exhibited better overall talent, Ehmke’s off-speed “junk,” pitched from the right side, could tie the slugging, fastball-hungry Cubs into knots.

Onlookers figured Ehmke would be replaced after a few innings of the opener to disrupt the intentions of the Chicago starting lineup, a not-so-uncommon tactic in World Series play over the years. Yet the more Ehmke pitched in Game One, the more obvious he wasn’t going to be removed.

Ehmke was simply magical. He blanked the Cubs, inning through inning, in their own ballpark. In one stretch he struck out five consecutive batters. When Ehmke was done, he had scattered eight hits in a 3-1 complete-game victory, allowing just an unearned run in the ninth inning. He struck out 13 Cubs, a World Series record for the time and a stunning total for Ehmke, who averaged 3.3 Ks per nine innings over his career and reached double-figures in a game only one other time.

Ehmke’s performance put the Cubs’ hitting into an instant funk, as they struggled through the next two games. Slowly they crawled out of it, surviving a pitcher’s duel to win Game Three—their first triumph of the Series—then stormed out to an 8-0 lead in Game Four.

That’s when the world came crashing down upon the Cubs again.

When Al Simmons homered for the A’s in the bottom of the seventh off Guy Bush, the home crowd cheered it as a notation of respect. Yet a vast succession of singles tightened the score to 8-4, and two more were on base when Mule Haas drove a fly ball toward Hack Wilson in center field. The sun shining brightly in his eyes, Wilson lost sight of the ball—for the second time in the inning—and it fell behind him, allowing Haas to circle the bases with an inside-the-park home run that pulled the A’s to within one. Sheriff Blake, the third Chicago pitcher of the inning, couldn’t put out the fire; the A’s continued to bat around, and when Jimmie Dykes slammed a double to bring home two more runs, the damage was complete. The A’s had piled up a Series-record 10 runs in the inning, and the amazing comeback was preserved when Lefty Grove came in to silence the Cubs the rest of the way.

After the game, a despondent Hack Wilson pushed aside reporters and players and beelined to his four-year-old son, hugging him tearfully.

Anatomy of a 10-run Inning

Below are the blow-by-blow details of the A’s 10-run rally in Game Four of the World Series, erasing the Cubs’ 8-0 lead. All of the damage was done before the final two outs were made.

One game after erasing an 8-0 Chicago lead to take command of the World Series, the A’s put away the Cubs for good in Game Five with another stunning rally, overcoming a 2-0 ninth-inning deficit with three runs—the final stroke coming when Al Simmons scores on Bing Miller’s double. (Chicago Historical Society)

The Cubs, emotionally drained and on the edge of elimination, gave it their best in Game Five. Chicago starter Pat Malone allowed just two hits through the first eight innings, while the Cubs sneaked two past Ehmke, in a more mortal second start of the Series. But the A’s played the comeback role once more. Trailing 2-0 in the ninth, Philadelphia rallied behind a two-run homer by Haas and a game-winning, two-out double by Bing Miller off Malone that put the Series to rest.

Connie Mack climaxed his long and steep climb back atop baseball’s pinnacle with one of the game’s greatest achievements in strategy. Besides the stroke of genius in starting Ehmke, he never started his star lefties, Lefty Grove and Rube Walberg—tactfully saving them for long relief roles. They were effective enough against the right-handed power of the Cubs’ bats; Grove saved two games, Walberg won Game Five in relief.

Howard Ehmke’s ultimate second chance in baseball would be his last hurrah. He would stay with the A’s in 1930, but not for long—appearing in three games and ringing up an 11.70 ERA. His career would be over with 166 wins, 166 losses—and one World Series triumph he lobbied for, diligently scouted, and thoroughly earned.

Forward to 1930: The Big Blastcast of 1930 All but washed up, veteran pitcher Howard Ehmke gets the dream call for Game One of the World Series and delivers, setting the tone for a long-overdue championship for the Philadelphia A’s.

Forward to 1930: The Big Blastcast of 1930 All but washed up, veteran pitcher Howard Ehmke gets the dream call for Game One of the World Series and delivers, setting the tone for a long-overdue championship for the Philadelphia A’s.

Back to 1928: A Ruthian Rout World Series underdogs, a beat-up New York Yankees squad comes alive behind Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig.

Back to 1928: A Ruthian Rout World Series underdogs, a beat-up New York Yankees squad comes alive behind Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig.

1929 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1929 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1929 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1929 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1920s: …And Along Came Babe Baseball becomes the rage thanks to increased offense and the magical presence of Babe Ruth, whose home runs exert a major influence upon the game for ages to come.

The 1920s: …And Along Came Babe Baseball becomes the rage thanks to increased offense and the magical presence of Babe Ruth, whose home runs exert a major influence upon the game for ages to come.