THE YEARLY READER

1926: One Hell of a Hangover

A memorable finish to a seven-game World Series involves a terrific relief performance from a barely prepared—and hungover—Pete Alexander, and a historic, ill-fated stolen base attempt by Babe Ruth.

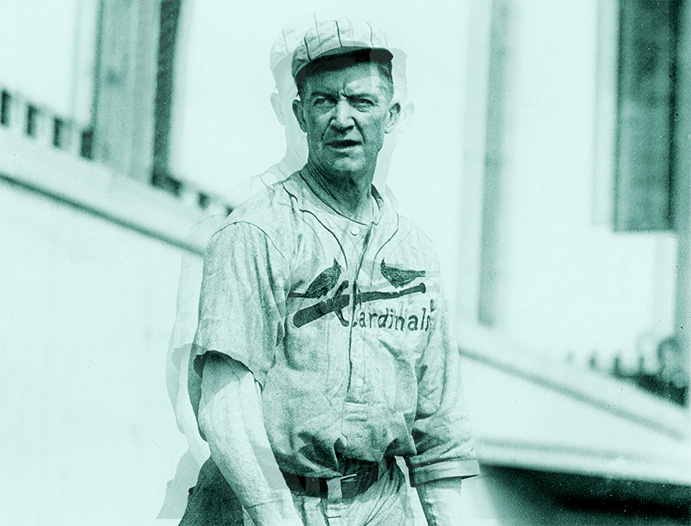

At age 39, Pete Alexander had lived a life of fame, torture and addiction to the bottle. Such demons failed to derail a magnificent, historic—and unexpected—relief appearance in Game Seven of the World Series against the New York Yankees. (The Rucker Archive)

Pete Alexander thought he had thrown his last pitch of the 1926 season.

Having tossed his second World Series victory over the New York Yankees the day before, Alexander celebrated the only way he knew all too painfully how—by drinking. He would then stumble into the bullpen the next day, wishing his St. Louis Cardinals teammates luck in Game Seven.

Little did “Old Pete” realize that he wasn’t yet done for the year.

As a rookie with the Philadelphia Phillies fifteen years earlier, Alexander served instant notice to the baseball world that he was a force to be reckoned with by winning 28 games. His best was yet to come; he won 30-plus games three straight years during the 1910s, upgrading an otherwise decent Phillies team to contention and, in 1915, a World Series appearance.

Then came World War I. Drafted straight to the front lines of France, Alexander became rattled from the intense amount of shelling, resulting in a partial loss of hearing.

Upon his return to the States—and his new ballclub, the Chicago Cubs—Alexander discovered one more unwanted side effect from his wartime duty; a growing number of epileptic seizures. Additionally, Alexander’s reliance on alcohol—something of a problem for him before the war—dramatically increased to numb the physical and psychological effects of the experience in the trenches. It slowly began to unravel his personal life, but not his pitching. In his first seven years back after World War I, Alexander averaged nearly 18 wins a season for the Cubs and maintained a healthy earned run average in the face of the expanded offense of the 1920s. All this, and he was fast approaching 40 years of age.

Then came Joe McCarthy. The rookie manager of the Cubs, though highly touted for his success piloting in the minors, had no major league experience as either player or manager. That gave Alexander, the hardened 39-year-old staff ace, immediate reservations about an untested skipper.

Quickly asserting himself as a disciplinarian that would help lead his teams to numerous pennants and World Series titles over the years, McCarthy clashed with Alexander—and vice versa. The new manager was especially concerned with Alexander’s intensified drinking habits, and when Alexander started the 1926 season in subpar fashion—he was only 3-3 by late June—it was enough for McCarthy to justify a move. He released Alexander—not even bothering to trade him—by putting him on waivers.

There was one taker: The St. Louis Cardinals.

Branch Rickey, the Cardinals’ crafty vice president, had made a name for himself by building up his team from within, not from purchasing or trading for established players. But then again, he had no choice; the Cardinals he came to a decade earlier were a financial mess, never a winner, and playing in one of the majors’ smaller marketplaces—a two-team one at that—which handicapped Rickey’s options of finding a more profitable solution.

That solution—the creation of a farm system—wasn’t entirely without precedent; Rickey merely perfected it into an art form. The Cardinals expanded their minor league network and collated them by classification so that players could move “up the ladder” to the parent club. Rickey, a master of eyeing the right talent, had enough minor league teams under his belt by the early 1920s to bolster his basic argument for the farm system: “If you dig up enough rocks, a small percentage of them will become gems.” And what of the lesser gems? He could sell those to other teams for decent money.

Though other team owners, and commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis in particular, frowned on the farm system idea as an imperialistic, “chain store” concept, Rickey’s innovation was a justifiable way to combat the high-priced spending of the “haves” in baseball.

The Cardinals’ inner-growth philosophy began to pay off, dwindling their long-term debts while producing long-overdue results on the field. At the outset of the 1926 season, every player in the Cardinals’ starting lineup had spent his entire major league career in St. Louis.

As the Cardinals slumbered into June trying to stay above .500, Rickey had to look for “outsiders.” It was then he saw the name of Pete Alexander on the waiver wire, and nabbed him at marginal cost.

Alexander couldn’t have enjoyed a more satisfying first week with his new team. In his first start for the Cardinals, he faced McCarthy’s Cubs—and beat them, 3-2, allowing just four hits. At the same time, the Cardinals began to take off in the standings.

Alexander’s rebirth at St. Louis didn’t ignite the Cardinals at first, as the team continued to play average ball through July. But in August they found their groove, winning 22 of 28 to end the month—capped by a doubleheader triumph over the fading Pirates that pushed St. Louis into first place. September gave the Cardinals new competition from the Cincinnati Reds, sporting a league-high .290 batting average and a star-studded rotation that included Carl Mays, Eppa Rixey, and 20-game winner Pete Donohue. Yet a six-game Cincinnati losing streak in the season’s waning weeks killed any hope of a Red celebration.

St. Louis took its first-ever pennant with second baseman Rogers Hornsby at the helm. In his five previous years, the “Rajah” had stunned fans with an overall batting mark of .402, while averaging 29 home runs and 120 runs batted in per season. His numbers slumped in 1926 to .317, 11 and 93, but he could be forgiven; he dealt with recurring thigh and back injuries, losing 15 pounds as a result. Off the field, Hornsby was also likely consumed with the failing health of his mother in Texas. When she died on the eve of the World Series, Hornsby—always known for making few friends with his blunt and icy disposition—was softly grilled by the press for prioritizing baseball over a funeral. However, the fact was that his family had told him to carry on, so he did.

Completing a swift and impressive rebuilding program, the New York Yankees rebounded to face the Cardinals in the World Series.

Powerful new blood had injected itself into the Yankees lineup. New faces included 22-year-old second baseman Tony Lazzeri, who the year before had obliterated Pacific Coast League pitching to the tune of 60 home runs and 222 RBIs at Salt Lake City, elevation 4,000 feet. Facing tougher pitching and sea level conditions as a rookie in New York, Lazzeri still applied enough punch to produce 18 homers with 114 RBIs.

In his second season as an everyday regular, Lou Gehrig further established the Yankees’ return to championship normalcy. For his part, Gehrig would bat .313, rake out 83 extra base hits (including an AL-leading 20 triples) and score 135 runs.

But most of all, Babe Ruth was back after his sickly, strife-torn 1925 effort. The Sultan of Swat recaptured the AL lead in home runs, RBIs, walks, and runs scored.

Wearing the Triple Frown

Seven times over his career, Babe Ruth led the AL in two of the three categories needed to win the hitter’s triple crown. On three of those occasions, as shown below, he finished runner-up in the third category—and barely.

The Yankees went from a team of question marks to one of exclamation points in 1926, tearing into first place early and coasting to their fourth pennant in six years. New York received a brief scare after Labor Day from the Cleveland Indians, managed for the last time by Tris Speaker. But the Indians’ last-minute rush was too little, too late. The Washington Senators’ two-year rule over the AL ended with a fourth-place finish; aging pitchers Walter Johnson and Stan Coveleski shouldered too much of a burden for a depleted staff that played musical chairs with its starting rotation.

BTW: Speaker would be brought down after the season by rising accusations that he and Ty Cobb fixed a game in 1919.

Babe Ruth made for a public sideshow days before the World Series by visiting a New Jersey hospital and promising an 11-year old named Johnny Sylvester—reportedly dying from a case of blood poisoning—that he would hit a home run in the World Series just for him.

The kid’s condition must have deteriorated after hearing about the Yankee offense, limited to a total of four runs and 15 hits through the first three games. Fortunately for New York, they got one win out of it when Herb Pennock outdueled Bill Sherdel in Game One. But Alexander shut the Yankees down in Game Two, 6-2—retiring the last 21 batters he faced—and Jesse Haines shut them out in Game Three, 4-0.

In Game Four, Ruth awoke—and Johnny Sylvester started improving dramatically, so they said. Ruth crushed three home runs, a career first, in his first three at-bats at Sportsman’s Park. The 10-5 rout gave New York the momentum to take the series lead when Pennock again outlasted Sherdel in a come-from-behind, 3-2 Game Five win in 10 innings.

Legend has it that 11-year old Johnny Sylvester lay near death when he was “saved” by Babe Ruth, who made good on a promise to hit a home run for him at the World Series. Sylvester went on to live a long life, though it took him three years to fully recover from the blood poisoning that led to his fame. He served in the Navy during World War II and later became president for a package machinery manufacturer; he died in 1990 at the age of 74. (The Rucker Archive)

For Game Seven, the Cardinals took early control when they sneaked three unearned runs off Yankees starter Waite Hoyt in the fourth. But the St. Louis lead was cut to one in the sixth and, an inning later, Cardinals starter Jesse Haines ran into bigger trouble. Though he had gotten two outs, the bases were loaded—and worse, a blister had developed on the index finger of his pitching hand. The dangerous Tony Lazzeri was at the plate. Hornsby came over from second base to play manager, looked at Haines’ finger, then peered toward the St. Louis bullpen.

He wanted Alexander.

Alexander looked to be in no condition to enter into this critical moment. He had quelled his celebratory drinking binge of the night before as only an alcoholic could—by continuing to drink. Pitching mate Flint Rhem claimed to see Alexander alternately napping and taking swigs from a pint of whiskey kept hidden under his jacket. Nevertheless, Alexander answered the call.

BTW: St. Louis third baseman Les Bell insisted, in a 1978 Sports Illustrated article, that Alexander was not inebriated.

On the mound, Alexander told Hornsby he was fine and refused to throw any warm-up tosses—Lazzeri might catch on to his state of being. To work he went. The first pitch missed; the second nailed the strike zone with Lazzeri looking. The Yankee rookie didn’t watch the next offering; he launched a drive that keyed in on the left-field foul pole—then curved just foul for a second strike.

The long strike, it turned out, was Lazzeri’s best shot. He swung and missed at the next pitch, and Alexander completed a bailing out of one of baseball’s most historic bases-loaded jams.

Tony Lazzeri strikes out to end the famous sequence between him and a cold, hungover Pete Alexander. Just one pitch earlier, the impressive 22-year-old Yankee rookie had missed a home run just feet from the foul pole.

With Bob Meusel at the plate—and Lou Gehrig on deck—Ruth sensed Alexander’s condition and figured he could get a terrific jump on him. So Ruth tore for second on the very first pitch. Cardinals catcher Bob O’Farrell was keeping a close enough eye on the situation, and fired to Hornsby at second—who applied the tag successfully on Ruth, ending a most memorable Game Seven.

The Cardinals’ triumph was the successful terminus of a decade-long road from neglect to respect, giving the Mound City its first world title in 40 years.

Pete Grover Cleveland Alexander, for better or worse, would surely drink to it.

Forward to 1927: The Yankee Juggernaut The 1927 New York Yankees—the team often considered as the greatest ever—sweeps away the competition.

Forward to 1927: The Yankee Juggernaut The 1927 New York Yankees—the team often considered as the greatest ever—sweeps away the competition.

Back to 1925: An Intestinal Excess The good life—or too much of it—finally catches up with a bloated Babe Ruth.

Back to 1925: An Intestinal Excess The good life—or too much of it—finally catches up with a bloated Babe Ruth.

1926 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1926 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1926 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1926 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1920s: …And Along Came Babe Baseball becomes the rage thanks to increased offense and the magical presence of Babe Ruth, whose home runs exert a major influence upon the game for ages to come.

The 1920s: …And Along Came Babe Baseball becomes the rage thanks to increased offense and the magical presence of Babe Ruth, whose home runs exert a major influence upon the game for ages to come.