THE YEARLY READER

1914: The Miracle Braves

After a typically depressing start, the hapless Boston Braves stagger the baseball world with one of the game’s biggest comebacks; meanwhile, the Federal League begins business.

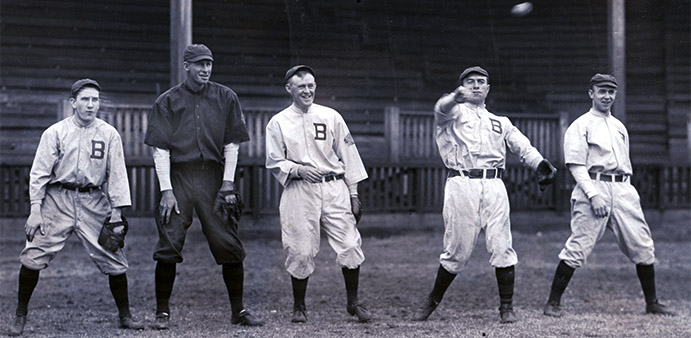

Johnny Evers (center) spreads smiles among his Boston Braves teammates in pregame warm-ups. The veteran second baseman’s leadership was crucial to the Braves’ stunning midseason turnaround. (The Rucker Archive)

It appeared to be business as usual for the Boston Braves.

They had just reclaimed the National League basement after being swept in a doubleheader against Brooklyn, running their losing streak to five. Adding insult to incompetence, they then traveled to Buffalo to play an exhibition against the town’s minor league team—and lost, 10-2.

With a 26-40 record in early July, the Braves were doing what they had been doing for 10 years: Looking up in the standings. Way up.

But from that abysmal day in Buffalo lay the foundation for one of baseball’s unlikeliest and greatest rises from oblivion. And when the season concluded in October, the rampaging Braves would completely lay waste to everyone within their path—including the three-time defending NL champion Giants, and the high-powered Philadelphia Athletics in a stunning World Series sweep.

For a decade, Boston had been the NL’s perennial derelict. It certainly wasn’t for a lack of instability. Over this period, the team averaged nearly 100 losses a year under seven different managers, four different owners, and under four different nicknames. While other teams stayed competitive and moved into steel-and-concrete palaces, the Braves played their dreadful brand of ball in a rickety wooden ballpark with 10,000 seats—most of them rarely occupied.

Before 1912, the franchise was purchased by former star pitcher John Montgomery Ward and two former high-ranking New York policemen, James Gaffney and John Carroll. Under their leadership, the team didn’t make any immediate inroads on the field. But at least they gave the team a name that would stick: The Braves.

In 1913, the Braves named as their manager George Stallings, who like Connie Mack wore suits in the dugout, but like John McGraw had a vicious temper—even worse, many claimed. Stallings prodded the Braves to a 69-82 record, which by the numbers was his worst managerial performance over the past 10 years. But it was a godsend to the Braves’ faithful; it was Boston’s best finish since 1902.

For 1914, Stallings chucked away veteran players he felt had stuck around too long, injected more youth into the starting lineup and made one newsworthy acquisition. Johnny Evers wanted no part of being with the Chicago Cubs any longer and threatened to jump to the Federal League; instead, he signed with the Braves for a nice salary. The long-time second baseman was not a superstar slugger who could carry a team offensively, but his experience playing for and managing a consistently successful unit like the Cubs would engender him into a critical leadership role in Boston.

BTW: Using the rival Federal League as leverage, Evers was able to forge a $25,000 deal with the Braves that would have been unthinkable before the advent of the FL.

The Braves’ start to 1914 showed zero signs of what lay ahead; they won four of their first 22 games. They rebounded and became more competitive, but then came the five-game collapse and the embarrassment at Buffalo in early July.

Using the loss against the minor leaguers at Buffalo as a rallying point, Evers challenged his team to start believing in itself. The Braves met the dare, winning 12 of their next 16 games—all on the road. This propelled Boston all the way from last place to fourth in a suddenly bunched-up NL race.

Upon returning to Boston, a 14-game homestand produced 12 more victories, an upgrade to second place, and a showdown with the only team left ahead of them: The New York Giants.

Angling for an unprecedented fourth straight NL title, the Giants were performing nowhere like the team that had won it the previous three years. With the exception of second-year outfielder George Burns, no one seemed to be stepping it up at the plate for manager John McGraw. And on the mound, pitcher Rube Marquard—who reached star status with a 19-game win streak two years earlier—suddenly seemed to lose it at midseason, with many pointing to an exhausting 21-inning performance against Pittsburgh in July that may have deadened his arm.

BTW: Marquard lost his remaining 10 decisions on the year following his marathon start against the Pirates, finishing at 12-22; though he would show better results in future years, he would never regain the form that earned him 73 wins between 1911-13.

Though his Giants were ahead of the Braves by 6.5 games, McGraw acted as if he was ready to concede the flag to Boston when the Braves came to the Polo Grounds. Unfortunately, his intuition paid off; the Braves swept the Giants in three, capping the sweep with a 10-inning, 2-0 win over Christy Mathewson.

The Miracle Braves’ steamrolling continued, eventually catching up and tying New York for first place—just as the Giants came to Boston for a return engagement in early September.

With the entire city of Boston now abuzz, the neighboring Red Sox graciously allowed the Braves to play their remaining home games at Fenway Park—a much newer facility with three times as many seats as the South End Grounds. The park was put to good use; over 91,000 attended the series against the Giants, with the Braves winning two of three.

With that, Boston took sole command of first place by capping off a remarkable streak in which it won 36 of 46 games. The Braves didn’t pause to celebrate; they won 25 of their remaining 31 games and outdistanced the Giants by a stunning 10-game margin at season’s end.

BTW: The Braves were 68-19 after reaching their mid-season nadir.

Start as Chumps, Finish as Champs

No eventual World Series champion built a bigger hole for themselves than the Boston Braves; here’s the list of other trailers who were well below .500 before rebounding to an October triumph.

Everyone got a chance to donate under manager Stallings, who worked his magic through platooning, a tactic generally oft-used in the majors at the time. Yet it was hard to look at the team’s offensive numbers—especially its middle-class .251 batting average—and conclude they were overpowering. But the Braves got their hits and scored their runs when it counted, as evidenced by their many come-from-behind victories during their second-half dash.

On the mound, Stallings relied almost exclusively on a three-man rotation during the team’s phenomenal second half. His two best pitchers of 1914—right-handers Dick Rudolph and Bill James—had made so little career noise coming into the season, their white-hot numbers from July on were all the more jarring, each winning nearly 20 games after the Buffalo debacle. The Braves’ winning momentum even became contagious for their subpar players, who briefly rose to stellar heights. Oft-used pitcher George Davis wedged in a start between the regular rotation on September 9 and proceeded to throw the NL’s only no-hitter of the year; it was just one of seven career victories for Davis.

While the National League was turned upside down, the Philadelphia Athletics remained at the American League forefront in more conventional fashion. They seldom were challenged and won 99 games, claiming their fourth AL pennant in five years with room to spare.

There were no surprises on the Philadelphia roster, which remained as potent and well-oiled as before. The A’s offense led all major AL categories, and was anchored again by Eddie Collins (.344, 122 runs scored and 58 steals) and Frank “Home Run” Baker, who led the AL in his nickname for the fourth straight year.

Philadelphia’s top two veteran pitchers, Eddie Plank and Chief Bender, were used more sparingly yet remained just as effective. They were complemented by a fine young batch of hurlers, including Bullet Joe Bush, Bob Shawkey, Herb Pennock, Weldon Wyckoff and Rube Bressler—all of whom were 23 or younger. The pitching duties became so socialist, the 1914 A’s became the first league champion without a 20-game winner.

With his staff awash in solid young talent, manager Connie Mack had to say no to another bright pitching prospect first offered to him by cash-strapped minor league owner Jack Dunn in Baltimore. Rebuffed, Dunn next turned to the Boston Red Sox, who said yes—and thus welcomed 19-year-old George Herman Ruth, better known as Babe Ruth, into their fold.

BTW: The Cincinnati Reds were also offered Ruth, but they instead chose two other ballplayers from Dunn who would make no impact whatsoever.

While many went by the numbers and predicted a Philadelphia rout of the Miracle Braves in the World Series, others were wisely reading between the lines and foretelling something different. One simply had to look inside each team’s clubhouse to understand the latter point of view.

In sharp contrast to the Braves’ totally unified team enthusiasm, there was trouble brewing among the Athletics. Dissension led to bitter factions; some players felt they could make a better living in the rival, upstart Federal League, while others chained their loyalty to Connie Mack—and felt betrayed by those who didn’t. The internal strife failed to damage the A’s regular season performance, but it wasn’t about to help them against the rampaging Braves.

The Braves employed their 1-2 punch of Dick Rudolph and Bill James for the first two games at Shibe Park, and it completely muted the A’s powerful bats. Rudolph won Game One, scattering five hits in a 7-1 triumph, while James tossed a two-hit shutout in Game Two. Back “home” at Fenway Park, James came to the rescue of starter Lefty Tyler in Game Three, pitching two scoreless innings of relief and allowing the Braves to post a 5-4, 12-inning victory. With nothing left emotionally, the A’s were finished off by Rudolph in Game Four, 3-1.

With their sudden success and fame too big for their small and decrepit ballpark, the Braves were allowed to move their home games late in the year to Fenway Park, the two-year-old home of the Red Sox. This panorama was taken during Game Three of the World Series, won in thrilling fashion by the Braves in 12 innings, 5-4. (The Rucker Archive)

Even for those who sensed a Boston upset, this was startling. Rudolph and James each got credit for two victories, combining to allow just one earned run over 29 innings. The Athletics batted just .172 and were left utterly demoralized.

It was the first time the World Series ended in a sweep.

Connie Mack had clearly seen the writing on the wall left by his ballplayers. It was time for a change. A big one.

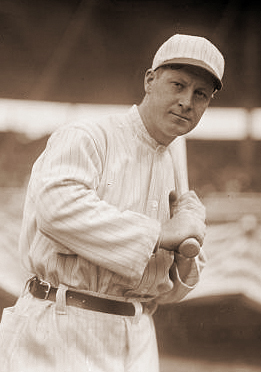

No one took better advantage of the Federal League than Benny Kauff, who catapulted his status from that of an unknown minor leaguer to a brash star hitter in the upstart circuit. (Library of Congress)

The Federal League opened shop to the masses in 1914, with eight teams playing out of rebuilt or brand new ballparks. Among them: Chicago’s Weeghman Park, later to be known as Wrigley Field. Fan interest wasn’t bad to begin with, but the reality of the competition between the three major leagues slowly began to set in. Still, the Feds’ first season was a qualified success, complete with a competitive pennant race where just 25 games separated first place and last—an even tighter fit than the dizzying NL battle won by the Miracle Braves.

While many marquee names in the new league performed as expected, others who migrated from the benches of the two established leagues became stars in their own right. At the top of that list was, unarguably, Benny Kauff of the Indianapolis Hoosiers. A 24-year-old outfielder with only 11 previous major league at-bats to show for, Kauff became the Feds’ instant answer to Ty Cobb, leading the league in batting average (.370), runs (120), hits (211), doubles (44) and steals (75). A man of flamboyant character, Kauff lived up to his newly acquired superstar image, and his contributions led Indianapolis to the FL’s first flag, besting Joe Tinker’s Chicago ChiFeds by a game and a half.

For Kauff and the Feds, 1914 would be the life of Riley. Unfortunately for both, life would be far less kind in the future.

Forward to 1915: The Great Connie Mack Fire Sale Sensing bad vibes and bad finances, Philadelphia A’s manager Connie Mack tears apart his first dynasty.

Forward to 1915: The Great Connie Mack Fire Sale Sensing bad vibes and bad finances, Philadelphia A’s manager Connie Mack tears apart his first dynasty.

Back to 1913: Giant Bridesmaids, Again Not even good luck charm Charlie Faust can save the New York Giants from another World Series defeat.

Back to 1913: Giant Bridesmaids, Again Not even good luck charm Charlie Faust can save the New York Giants from another World Series defeat.

1914 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1914 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1914 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1914 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1910s: The Feds, the Fight and the Fix The majors suffer growing pains as they deal with a fledgling third league, increased scandal and gambling problems, and a brief interruption from the Great War.

The 1910s: The Feds, the Fight and the Fix The majors suffer growing pains as they deal with a fledgling third league, increased scandal and gambling problems, and a brief interruption from the Great War.