THE YEARLY READER

1906: The Hitless Wonders

Despite a basic inability to make contact with the baseball, the Chicago White Sox use resourceful offensive tactics (and great pitching) to make a stunning run and become one of the game’s unlikeliest champions.

Chicago player-manager Fielder Jones leads his punchless White Sox by example, laying down a bunt in an attempt to reach base safely. (Library of Congress—CHS)

It was a classic matchup of heavyweight versus featherweight. In one corner, representing the north side of Chicago: The Cubs, masters of the National League, with dominant hitting, slugging, fielding and incredible, stifling pitching that led to 116 wins, 36 losses and an all-time best .763 winning percentage.

In the other corner, representing the city’s south side: The White Sox, who somehow, some way, managed to snag an American League title despite owning the league’s worst batting average (.230) while hitting a grand total of seven home runs on the entire season.

The 1906 World Series was built up as a laughable mismatch of Windy City rivals, but anyone who believed the White Sox could be blown away by a mere breath of Cub supremacy was in for a major surprise. The White Sox proved true the baseball adage that you can’t win without good pitching—and added to it by proving you could win without good hitting.

The White Sox had become no strangers to winning ballgames by attrition; the year before, the team’s mix of superior pitching and inferior hitting had left it only two games shy of an AL pennant. The winning knack began in 1904 when outfielder Fielder Jones took over as manager for Nixey Callahan; both were tough men who could strike fear in players operating at less than 100%, but Jones possessed a skillful modern-day discipline that Callahan, a brawling throwback to the raucous 1890s, lacked.

Whether or not by design, hitting had become a luxury for Jones and the White Sox; pitching was truly the name of their game. The team’s four main starters, all at or near their prime, had no holes to exploit. Frank Owen and lefty Nick Altrock were perennial 20-game winners. Doc White, another southpaw, was perennially robbed of winning 20 despite yearly earned run averages below 2.00. And the fourth member of the pack, the relative kid at 25, was spitballer Ed Walsh—whose emerging durability would soon make 20 wins a mere midseason milestone.

Perhaps White Sox pitching worked doubly hard to achieve such brilliance on the mound since, if they played any less, they were bound to lose. Such was the pressure to throw with little offensive backbone to lend.

For any player to hit over .250 for the 1906 White Sox was to be kissed on the feet by his pitching staff. Only three everyday starters did: Second baseman Frank Isbell (the team leader at .279), veteran switch-hitting shortstop George Davis (.277) and first baseman Jiggs Donahue (.257). Jones, playing regularly in the outfield while managing, matched the team average of .230. Third baseman Lee Tannehill hit .183. Catcher Billy Sullivan was at .214. The majority of the benchwarmers hit well below .200. Even two early-season arrivals with rich hitting pasts couldn’t budge the numbers upward: Eddie Hahn (a .319 rookie hitter with the New York Highlanders in 1905) and Patsy Dougherty (a career .301 hitter) both toed the party line and hit around .230 in Chicago.

And then there were the home runs—or the lack of them—being hit by the White Sox. The team total of seven, while not light years from what other major league teams produced in the prime of the deadball era, was still an embarrassment. Jones and Sullivan represented the Sox’ boomers with two homers each.

BTW: The White Sox’ slugging inertia would get worse before it got better; the team would combine to hit three home runs for all of 1908.

Powerless, But not Helpless

Over the AL’s first decade of major league business, the White Sox easily hit fewer home runs than any other team—yet only the Athletics had a better overall record.

As bad as the White Sox were at poking out base hits, they were otherwise resourceful in making up for their slugging shortcomings. They were good at taking ball four, good at getting hit and good at bunting runners closer to home—as evidenced by their league-leading numbers in walks, hit batsmen and sacrifice hits. The White Sox’ accessorial ways of offense proved how, in spite of their rock-bottom numbers in batting and slugging, they managed to place third among AL teams in scoring. For this, Chicago sportswriters branded the White Sox with a nickname for the ages: The Hitless Wonders.

The White Sox struggled through the first few months of the regular season not so much for a lack of offense but an excess of pain. Injuries so badly crippled the team, owner Charles Comiskey took the then-superfluous step of bringing in a trainer from a nearby college. The Sox eventually healed up, but time was running out; by the end of the July, they were stuck in fourth place, trailing the defending AL champion Philadelphia Athletics by 7.5 games. But the three teams ahead of the Sox began to glitch over the next three weeks. The A’s were 7-14 over this stretch. The second place Highlanders, 5-12. Third place Cleveland, 8-10.

And the White Sox were 19-0.

No team in major league history had won as many games in a row, and no AL team would win more for almost 100 years. The White Sox catapulted into first place by 5.5 games at the end of the streak by virtue of sensational pitching; eight of their 19 wins were by shutout, including five from Ed Walsh.

BTW: Walsh’s five shutouts, over a 15-day period, would help him lead the AL at year’s end with 10.

The White Sox were on top but not completely in the clear. In early September, the Highlanders came roaring back with a 15-game win streak, 10 of which came from doubleheader sweeps over five consecutive days, to retake the lead. Losing three of four at New York with less than two weeks to go in the season didn’t help the White Sox’ cause, but then Chicago reeled off five straight wins of their own—while the Highlanders slumbered to the finish, handing the White Sox their first pennant since taking the flag in the AL’s inaugural 1901 campaign.

Batting warts and all, the White Sox were able to stake their claim as the best team in the AL. Now they had to convince the rest of Chicago that they were the best team in town.

Like the White Sox, the Chicago Cubs had spent the past few years playing just good enough not to win a pennant. And as with Fielder Jones with the White Sox, the Cubs had performed a recent midseason managerial switch by promoting from within. First baseman Frank Chance took over in mid-1905 after Frank Selee was forced to step down with a worsening case of tuberculosis. Like Jones, Chance—a former boxer—was a fighter on the field and with his players, but he put more faith into his teammates to improvise and play on their intuitions rather than wait for his next signal.

BTW: Selee initially wanted third baseman Doc Casey to be his replacement, but Cubs players successfully lobbied in giving the job to Chance.

Given all but carte blanche under first-year owner Charles Murphy, Chance showed he was as deft at building teams as he was running them. All his moves for 1906 worked. Third baseman Harry Steinfeldt came over from Cincinnati and batted a career-high .327, leading the National League in hits (176) and runs batted in (83). Pitcher Jack Pfiester, a left-hander with two short, failed big league trials at Pittsburgh, exploded with a 20-8 record. Jimmy Sheckard, popular with Brooklyn fans, unpopular with Brooklyn management, left the Superbas and became an important piece of the Cubs’ roster near the top of the order.

Even after the season had begun with the Cubs running neck-and-neck with the two-time defending NL champion New York Giants, Chance wasn’t done. He dealt for two pitchers, Orval Overall and Jack Taylor, both of whom posted identical 12-3 records at Chicago with near-identical ERAs of, respectively, 1.88 and 1.83.

BTW: Taylor’s return to Chicago signaled a hint of forgiveness from a Cubs team that had angrily shuffled him off after 1903, amid allegations of game-fixing.

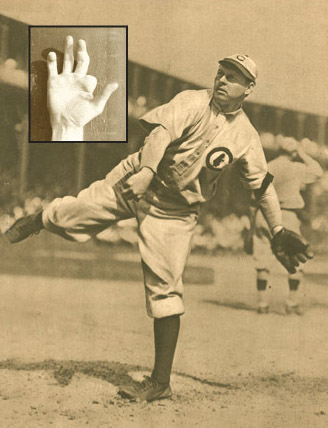

Overall and Taylor’s sterling contributions were simply par for the course with the rest of the Cubs’ pitching staff, whose 1.75 team ERA and all-time low .207 opposing batting average suffocated the opposition. Three Chicago starters finished one-two-three in the NL ERA race: Second-year lefty Ed Reulbach (19-4) finished third at 1.65; Pfiester checked in at second with 1.51; and the man leading it all—with a NL modern record-low ERA of 1.04—was 30-year-old Mordecai “Three Finger” Brown.

Mordecai “Three Finger” Brown used a hand (inset) mangled from a childhood farm accident to forge one of the great pitching careers in baseball history. In 1906, Brown’s 1.04 ERA was the lowest in National League history. (The Rucker Archive; inset, Library of Congress—CHS)

Brown was a right-hander missing part of his right hand. At the age of seven, Brown got his hand caught in a grain cutter; he lost his ring finger and a good chunk of his pinkie. For baseball, the expected handicap became the unanticipated advantage, as the unique shape of Brown’s hand allowed him to develop a devastating curveball. Now in his fourth major league season, Brown became the ace of aces on the Cubs with a 26-6 record that launched him on a remarkable four-year run; during this stretch, he would post 102 wins, just 30 losses and a stunning 1.31 ERA.

Chance was the catalyst from the dugout and from the top of the order, leading the league in runs (103), steals (57) and on-base percentage (.419). And the first baseman made up the “3” in the team’s sharp 6-4-3 double-play combination of shortstop Johnny Evers and second baseman Joe Tinker, soon to be made legendary through poetry.

The Giants won 96 games but could only view the Cubs from afar in the standings. Injuries took their toll on the defending world champs, but even if they’d been blessed with pure wellness, they couldn’t have rattled the Cub powerhouse.

Doing absolutely no wrong, Chance’s Cubs tore apart the NL with a 116-36 record that, by percentage, remains the greatest showing in modern major league history. The Cubs played well at home (56-21) but played even better on the road (60-15). They hit, scored, pitched and fielded better than anyone else. They finished the regular season hotter than hot, losing just eight of their final 63 games.

BTW: The 2001 Seattle Mariners won 116 games to match the Cubs’ record, but it took them 10 more games to get there.

People thought: Just who were the Chicago White Sox to be playing these guys in the World Series?

Some in the local press had dared to give the Hitless Wonders a chance against the mighty Cubs. Hugh Fullerton, the Chicago Tribune reporter later known for exposing the Black Sox Scandal, predicted a White Sox triumph—and had to beg his disbelieving boss into printing it after it was initially edited out.

The White Sox’ demonstration of offense early on in the 1906 World Series made their hitting incompetence of the regular season look like a prodigious power display by comparison. Through the first four games, the Sox totaled six runs and 11 hits for a sub-anemic batting average of .097—yet astonishingly managed a split against the Cubs.

In Game Five, a funny thing happened to the White Sox. They started hitting.

The White Sox would be aided at the plate for Game Five by an overflow crowd at the Cubs’ West Side Park that resulted in special ground rules, enhancing hitting conditions. As ground rule doubles were called for balls hopping into a roped-off crowd behind the outfielders, the White Sox collected. Their eight doubles—four by Frank Isbell—resulted in a breakout 8-6 win. The victory was all the more improbable, given the White Sox had to overcome six errors compared to none for the Cubs.

BTW: The White Sox committed 16 errors during the series; 10 of the 18 runs they allowed were unearned.

Champions by Attrition

The 1906 White Sox top the list of pennant winners with a sub-standard batting average. Note: With the exception of the 2015 Mets, all of the teams on this list went on to win the World Series.

Inspired with their sudden gluttony of offense, the White Sox banged away again in Game Six. They hammered Mordecai Brown—apparently exhausted after throwing two complete games over the previous five days—for seven runs on eight hits before the three-fingered marvel’s removal in the second inning. The Sox coasted to an 8-3 win and locked up one of the greatest upsets in World Series history.

Frank Chance gave the White Sox credit but refused to accept that the better team had won. That attitude would ultimately be the least irritating of matters for White Sox players. Charles Comiskey, showing off a duplicitous nature that would one day wreck his franchise, “rewarded” his team with a $15,000 bonus to be divvied up by the players immediately following the World Series. Little did the players realize that, for the moment, the money would amount to nothing more than an advance on their 1907 salaries.

It may have been the first time that Comiskey grandly shafted his players. It certainly wouldn’t be the last.

Forward to 1907: The Cultivation of a Georgia Peach Angrier than life, Ty Cobb comes of age and delivers the Detroit Tigers with their first pennant.

Forward to 1907: The Cultivation of a Georgia Peach Angrier than life, Ty Cobb comes of age and delivers the Detroit Tigers with their first pennant.

Back to 1905: The Zero Heroes Christy Mathewson and Joe McGinnity completely deny the Philadelphia Athletics in the World Series.

Back to 1905: The Zero Heroes Christy Mathewson and Joe McGinnity completely deny the Philadelphia Athletics in the World Series.

1906 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1906 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1906 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1906 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1900s: Birth of the Modern Age The established National League and upstart American League battle it out, then make peace to signal in a new and lasting era.

The 1900s: Birth of the Modern Age The established National League and upstart American League battle it out, then make peace to signal in a new and lasting era.