THE YEARLY READER

1903: The First World Series

The American and National Leagues finally agree to co-exist in peace, leading to an inaugural “world’s championship” between the two pennant winners.

An overflow crowd in Boston greets the Americans and Pittsburgh Pirates before the first World Series game ever played. (The Rucker Archive)

On January 9, 1903, the hatchet was finally buried.

It was on this day in Cincinnati that the powers that be for both the National and American Leagues began the process of co-existing harmoniously, ending two years of bitter fighting. Gone would be the player raids, the cutthroat crosstown rivalries and the clandestine undermining of each other.

Although nothing was said about the leagues playing one another—be it as regular season interleague play or postseason competition—the door was certainly propped open more widely than ever for the possibility.

Ironically, it was the National League—the established entity of big league baseball—that more or less waved the white flag to the relatively infant American League, singularly run by Ban Johnson. Talent and attendance had both swayed in favor of the AL, and there was still ongoing pilferage of NL rosters. Jack Chesbro, Jesse Tannehill, Willie Keeler and Sam Crawford had already defected to the junior circuit since the end of the 1902 season, and AL owners were closing in on signing Christy Mathewson, Tommy Leach, Vic Willis and Sam Mertes, among others. To stop the bleeding, the NL decided to put the emergency brakes on the feud and meet with Johnson.

Though the Cincinnati talks supposedly provided a level playing field between the leagues, there was no mistaking that Johnson and his AL owners were firmly in charge.

The NL magnates gave it the good ol’ college try anyway.

Johnson was initially asked by NL executives, led by president Harry Pulliam, to merge the two leagues—eliminating the four AL franchises doing business in NL cities, while allowing the other four to continue as part of a 12-team National League. An incredulous Johnson quickly rejected the idea and walked out, only to return four days later with his own list of demands—many of which he’d get. Johnson demanded that all existing player contracts be honored, allowing AL teams to hold onto the players snapped up from the NL; in return he would stop the player raids. Johnson also pledged not to follow through on his threat to move the Detroit Tigers to Pittsburgh—but only on the condition that he could move his tampered Baltimore franchise to New York. The NL reluctantly, though not unanimously, agreed to these key issues.

BTW: John Brush, who helped scuttle the Baltimore Orioles and now owned the New York Giants—where most of the released Orioles wound up—vehemently decried the American League’s move to New York.

Out of the Cincinnati talks came the National Agreement, the bylines from which both leagues would be run; and the National Commission, an executive group of three representatives from both leagues that would rule over the game. The three elected to the Commission were Johnson and two NL executives: Pulliam and Cincinnati Reds owner Garry Herrmann. On the surface, the AL appeared outnumbered 2-to-1 within the Commission, but it was a deceptive facade; Herrmann, a long-time pal of Johnson, brought a more impartial voice to balance out the trio.

The negotiating power and dominating presence of Ban Johnson proved one thing as the new season proceeded in April: It was he who now ran the whole show.

The shortest end of the peace stick would not be reserved for the NL, but for the players. They once considered Ban Johnson their savior for thumbing his nose at the reserve clause and encouraging them to jump to his fledgling circuit. But the AL-NL peace treaty also brought agreement by both leagues to respect each other’s roster sovereignty and, therefore, the reserve clause. The players were once again perpetually chained and enslaved to the owners.

Of all the teams hit hard by the pre-peace player movement following the 1902 season, no one was hit harder than the Pittsburgh Pirates—ironically, the team that had been least touched by player raids the year before. Defecting to the New York Highlanders were starting pitchers Jack Chesbro and Jesse Tannehill, who combined for 48 of Pittsburgh’s stunning 103 wins in 1902. The remaining starters—led by Sam Leever (25 wins, seven losses and a league-leading 2.06 earned run average) and Deacon Phillippe (25-9, 2.43 ERA)—helped jumpstart the Pirates from a sluggish start to 1903. Sagging in third place to start June, the Pirates won 15 straight—the first six by shutout, a major league record—to permanently reclaim their standing in first place.

The Pirates were able to retain their offensive firepower despite losing three position players (also to the Highlanders); but only one, weak-hitting shortstop Wid Conroy, was a starter in 1902. That was just fine for player-manager Fred Clarke, knowing he had an evolving shortstop who had long proven he could hit: Honus Wagner.

Clarke still had his star hitters, again led by Wagner. The Flying Dutchman took another NL batting title with a .355 average, placed second in slugging percentage behind Clarke, and stole 46 bases to boot. Clarke himself batted .351, and center fielder Ginger Beaumont hit .341 while leading the NL with 137 runs and 209 hits.

The Onus on Honus

At first sight, there was no doubting Honus Wagner’s ability to hit major league pitching—but managers were hard-pressed to find a position he could be comfortable with. As the table below shows, Wagner was given significant auditions almost everywhere on the field before he finally settled in at shortstop for 1903.

As his team coasted through the summer on its way to a 6.5-game finish over the second-place Giants, Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss felt comfortable enough that, by August, he had a thought regarding the postseason.

Unlike the Pirates, the Boston Americans did not suffer from any talent drainage during the off-season, and with improved results swarmed to the top of the AL standings. Though the Americans had a solid lineup at the plate, what really impressed opponents was the Boston pitching staff—which, save Nick Altrock’s one-time appearance, consisted the entire season of just five hurlers.

Despite the AL’s improved balance of talent since its 1901 inception, Cy Young continued to be the young league’s most dominant pitcher at age 36—leading the AL in wins, win percentage, shutouts and innings thrown.

At 36 years of age, Cy Young was the AL’s oldest pitcher—and still its best. Though he failed to win 30 games for the first time since joining the AL, Young remained remarkable, winning 28 of 37 decisions while recording a 2.08 ERA. Successfully pitching alongside Young were Bill Dinneen, whose 21 wins included six shutouts, and 24-year-old Long Tom Hughes, who added 20 victories after surviving 1902 with the ill-fated Orioles.

Offensively, the Americans had plenty of punch—their 48 home runs as a team would be the most in the AL until Babe Ruth exceeded the number all by himself 16 years later. Left fielder Patsy Dougherty, in only his second year, provided excellent leadoff numbers with a .331 batting average, 35 stolen bases and 106 runs scored, while veteran slugger Buck Freeman paced the league with 13 home runs and 104 RBIs. Freeman added other team highs in the extra bases department with 39 doubles and 21 triples.

Boston easily knocked off defending AL champion Philadelphia, which actually showed improved pitching thanks to a (almost) full year from Rube Waddell and an impressive debut for 20-year-old Chief Bender. It was offense, however, for which the A’s withered, notching nearly 200 fewer runs than in 1902.

BTW: Waddell skipped on the rest of the season after August so he could appear in a stage production of The Stain of Guilt.

So the prize of the American League belonged to Boston and its new owner, Henry J. Killilea, a Milwaukee lawyer whose brother Matthew initially owned the Brewers of 1901—before he sold and watched the team move out of Wisconsin to St. Louis. But Henry was having better success with his ownership, and in August the Americans were sitting comfortably atop first place when he received a note from Barney Dreyfuss. The Pittsburgh owner, fully aware that both the Pirates and Americans were likely to win league pennants, proposed to Killilea a postseason series between the two teams to determine the true major league champion.

Killilea took it up with Ban Johnson, who shared in the Boston magnate’s delight at the chance to finally face the NL on the field. Though it was the established NL once again coming forward to make the offer, Johnson knew this was not a case of his league having nothing to lose and everything to gain. Self-assured that he was running the stronger of the two leagues, Johnson gave Killilea approval to go through with the offer—but was also stern in his desire to win. “Play them, and beat them,” Johnson told the Boston owner. “You must beat them.”

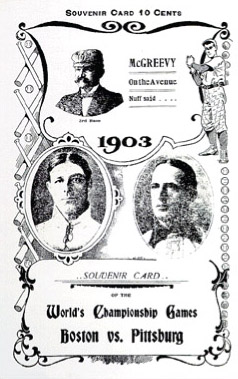

A dime would have bought you the scorecard for the first World Series, which was advertised here as the “World’s Championship Games.” (The Rucker Archive)

Dreyfuss and Killilea shook hands on the deal, and when both of their teams completed the regular season at the top of the standings, the “Championship of the United States”—or the World Series, as it would be called later—was on.

The Pirates were a tortured team by October. Honus Wagner was suffering from a beat-up right leg. The pitching staff, managing all season with decreased talent, saw its problems magnify. Sam Leever’s arm was sore, reportedly as a result of some trapshooting on the side. More troubling was the story of Ed Doheny, the third man in the rotation. Having seen his career turn around since joining the Pirates in 1901, winning 34 of 46 decisions, Doheny grew mentally unstable—at one point he fled from a game convinced he was being followed by “detectives”—and, shortly before season’s end, entered an insane asylum. He would remain there for the rest of his life.

This forced Deacon Phillippe to become the Pirates’ pitching workhorse during the series. Throughout the best-of-nine set, Phillippe would be called upon to make five starts—taking advantage of travel days and two rain postponements—to pick up the slack of the otherwise burdened staff.

Before a zealous, overflow crowd of 16,000 at Boston’s Huntington Grounds on October 1, the Pirates jumped on Cy Young with a two-out, four-run rally in the first inning, allowing Phillippe to coast to a 7-3 Game One triumph. In victory, Pirates outfielder Jimmy Sebring became a trivia answer for the ages when he hit the World Series’ first-ever home run. But Game Two showed a sign of things to come as an aching Leever lasted but one inning; the Americans evened up Pittsburgh, 3-0, on a three-hit shutout by Bill Dinneen.

BTW: From the very beginning, the temptation of game-fixing worked its way into the World Series: Boston catcher Lou Criger reported to Ban Johnson before Game One that he was approached by a gambler. Curiously, Criger made two errors in the first inning.

After Phillippe started and won the next two games, the Pirates led three games to one with the next three contests slated for Pittsburgh. Hopes seemed few and far between for Boston.

But the lack of depth in the Pirates’ pitching rotation reared its ugly head and allowed Boston to jump back and take command of the series. Brickyard Kennedy was shelled in Game Five, 11-2—and in Game Six, Leever managed to throw nine innings but lost to Dinneen, 6-3. When Young toppled Phillippe in Game Seven, 7-3, the Americans headed back to Boston with two games to win one—and the Series.

With two days’ rest, the Pirates threw Phillippe at the Americans for his fifth start. But it was Dinneen, making his fourth start, engineering his second series shutout with a 3-0 victory. Ban Johnson got his wish: The Boston Americans, representing the American League, were champions of the first World Series.

DEACON-STRUCTING BOSTON

With much of the Pittsburgh pitching rotation unavailable, Deacon Phillippe took charge and gave it all he had to put the Pirates past Boston in the World Series. But the other Pirates hurlers couldn’t pitch in with an equitably worthy share.

The Pirates appeared as a shell of their former selves in the series. Defensively, they were atrocious, committing a glaring 18 errors; 13 of those occurred over the last four games—all losses—leading to 11 unearned runs. Honus Wagner himself made six errors and batted a feeble .222 at the plate—though the latter figure wasn’t too far off par from the Pirates’ team average of .237.

Despite the loss, Dreyfuss was thankful enough for his team’s effort that he donated his share of the series gate to his players; each Pirate walked away after defeat with $1,316, not bad wages for the time. Because of Dreyfuss’ generous donation, coupled with Killilea’s refusal to give up his share (to the catcalls of many in the press), Boston players actually wound up earning less ($1,182) than those they had defeated. It was the first, and last, such imbalance in World Series history.

Killilea would end up selling the team at year’s end, mimicking the length of his brother’s tenure as major league owner, but surpassing it in results.

Most gratefully for baseball, the World Series finally showed what fans everywhere were wanting to see: A battle of the leagues on the field, not off it.

But thanks to the two Johns of New York—McGraw and Brush—ominous clouds would remain from the departed storm.

Forward to 1904: McGraw v. Johnson The World Series becomes a casualty of a continued feud between two of the games’s most powerful men.

Forward to 1904: McGraw v. Johnson The World Series becomes a casualty of a continued feud between two of the games’s most powerful men.

Back to 1902: Enemies Within the Gate Warfare between the American and National Leagues turns brutal with increased player raids and sabotage.

Back to 1902: Enemies Within the Gate Warfare between the American and National Leagues turns brutal with increased player raids and sabotage.

1903 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1903 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1903 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1903 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1900s: Birth of the Modern Age The established National League and upstart American League battle it out, then make peace to signal in a new and lasting era.

The 1900s: Birth of the Modern Age The established National League and upstart American League battle it out, then make peace to signal in a new and lasting era.