THE YEARLY READER

1902: Enemies Within the Gate

Warfare between the American and National Leagues turns brutal with increased player raids and sabotage.

The Rucker Archive

The American League won Round One of its war with the National League in 1901 just by surviving the first year with its dignity intact.

The upstart league would take Round Two a year later by bringing the older, more established NL to its knees.

Led by Ban Johnson, the AL set out in 1902 to prove that it would not be a one-hit wonder, that it could persevere and flourish in the face of its more veteran competitor. To achieve ongoing success, however, Johnson realized the AL could not stand pat.

Johnson provided more direct competition by moving the Milwaukee Brewers to St. Louis—where they would proceed to raid the crosstown NL rival Cardinals of most of their star players, including Jesse Burkett, Bobby Wallace and their three top pitchers—and would be known herein as the Browns. He also toyed with the idea of moving the Detroit Tigers to Pittsburgh, where they would muscle for attention against the powerful Pirates. But for the moment, he would wait until after the 1902 season to make that decision.

While Johnson was prompting AL team owners to continue raiding NL rosters, he had to be grinning over the NL’s continued internal disputes.

The eight NL owners were split right down the center over who should lead themselves. The debate raged into the 1902 season—and took crucial focus off the league’s struggle to deal with the nonstop player defections to the AL.

One faction, headed by tempestuous New York Giants owner Andrew Freedman, wanted to turn the league into a “trust” from which the eight teams would share in common stock. But Freedman’s plan did not call for equal allocation of shares, angering the four teams which saw their relative small holdings as a diminishment of their powers—not to mention the league’s competitive spirit. To publicly bolster its view, the anti-Freedman faction wanted Al Spalding, one of organized baseball’s founding fathers, to be elected the new NL president.

Months of seemingly endless quarreling, quorums, deadlocked votes and boardroom chicanery continued into the spring before a compromise was finally reached. The agreement called for a special commission, headed by Cincinnati owner John Brush, to choose a new president; eventually that man would be Harry Pulliam, an executive for the Pirates. With the dispute laid to rest, the NL finally turned its undivided attention to another huge, unresolved issue: Its fight with the American League.

One AL team that was truly frustrating the NL with its player raids was the Philadelphia Athletics. Having finished a strong fourth in 1901, the A’s staged a fierce, second wave of player raids upon the NL—again hitting the crosstown Phillies the hardest by swiping away star hitter Elmer Flick and pitcher Bill Duggleby. Already stung from losing top star Nap Lajoie to the A’s the year before, the Phillies finally got fed up with the lootings and took their unneighborly rival to court.

To the Phillies’ pleasant surprise, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court agreed, ordering the ex-Phillies—including 1901 pick-ups Lajoie and pitchers Chick Fraser and Bill Bernhard—back to where the reserve clause had bound them. But since this was a state decision, the court’s jurisdiction did not apply outside of Pennsylvania, and there the AL saw its chance to greatly absorb the court’s blow. It simply transferred Lajoie, Flick and Bernhard to Cleveland, where they could continue to play in the AL—so long as they never ventured into Pennsylvania to play against the A’s.

BTW: While Nap Lajoie and Bill Bernhard moved onto Cleveland, Chick Fraser and Bill Duggleby decided to return to the Phillies.

The NL attempted to stop player defections in other cities with similar lawsuits, but unlike Pennsylvania, state courts elsewhere ruled in favor of the AL, allowing players to stay. So while the NL was able to stir the mix and win a battle here and there, it was still badly losing the war.

Despite losing three of his biggest stars, A’s manager Connie Mack still had enough talent left over to make a run at the AL pennant. Veterans Lave Cross and Socks Seybold provided a solid punch for the offense, set up by leadoff man Topsy Hartsel (who defected from the Chicago Cubs). But after trailing defending AL champion Chicago early on, Mack needed more strength to fuel his chances of winning the pennant.

He picked up Danny Murphy, who had proven little with the Giants the previous two years, but flourished for Mack with good fielding at second base and a fine .313 batting average.

BTW: Murphy had a memorable AL debut on July 8 when he showed up two innings late and still collected six hits—one of those a grand slam—in a 22-9 win at Boston.

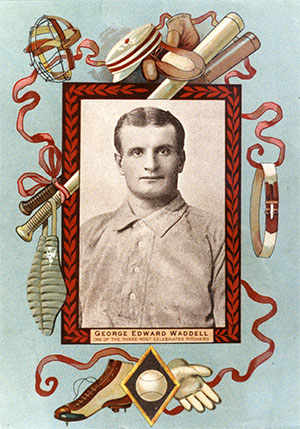

Mack then snagged pitcher Rube Waddell.

Though performing in the minors, Waddell had previously shown his major league worth playing four years in the NL. But his personality was a genuine piece of work. Waddell was picked up in Los Angeles playing for a team called the Looloos, an appropriate description for the 25-year-old lefty. Off the field—and occasionally on it—Waddell was as goofy as he was eccentric. His attention often wandered like that of a child, and he is legendary for being distracted on the field by the sound of a racing, ringing fire engine—for which he sometimes gave chase. But Waddell had improved from his NL years with a devastating fastball, for which he was tearing the minors apart. Rube’s playful yet problematic personality considered, Mack still couldn’t resist the chance to grab him.

In spite of an eccentricity that was sometimes intolerable, Rube Waddell won over his teammates in Philadelphia with 24 wins—all recorded after his June 26 arrival with the A’s. (The Rucker Archive)

Waddell delivered the goods and put the A’s over the top. Though he wouldn’t even don an A’s uniform until June 26, Waddell still racked up a 24-7 record with a stellar 2.05 earned run average and an AL-high 210 strikeouts; in July alone, he pitched his way to 10 wins, an AL record for any one month which still stands. A .500 team in the standings before Waddell’s arrival, the A’s were 56-27 with him and catapulted to the top of the AL—saving their best for last by winning of 20 of 23 games in one September stretch to ultimately finish five games in first.

While attention was being paid to a competitive race for the AL’s top spot, increasing awareness was being directed toward the Baltimore Orioles, entrenched deep down in the standings.

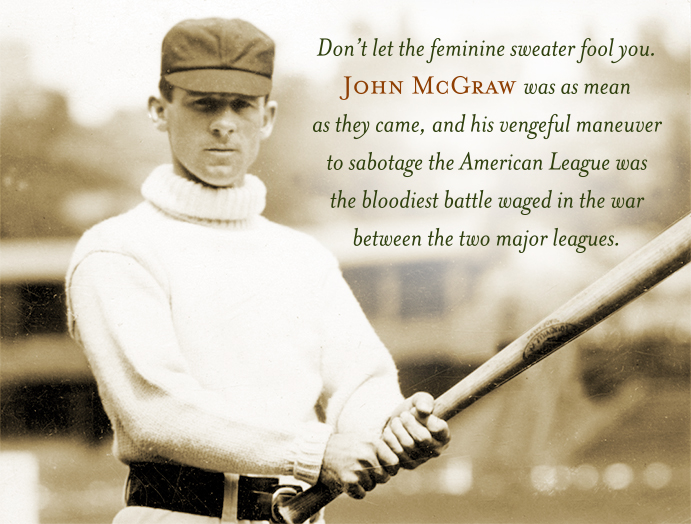

The Orioles were piloted by John McGraw, the diminutive yet fiery player-manager who specialized in a ruthless brand of umpire-baiting—a characteristic that went counter to Ban Johnson’s pledge to keep the AL clean and just. Johnson was making an unwanted habit of suspending McGraw for his repeated abuse of umpires, but with each slap given on the wrist, Johnson realized that McGraw wasn’t interested in his messaging. After one more incident in July, Johnson finally had enough and suspended McGraw—indefinitely.

McGraw, seeing his venture in the new league quickly turning sour, first got mad—then even, by calling John Brush. Just elected to head the NL’s Executive Council—and eager for any opportunity to do major damage to the AL—Brush was contacted and told by McGraw that the inside job of a lifetime was awaiting him.

Brush bought out McGraw’s majority interest in the Orioles and proceeded to trash the team. McGraw was released, and the New York Giants took him in as manager (where he would stay for the next 30 years). Brush then took many of the top Orioles players, including pitcher Joe McGinnity, catcher Roger Bresnahan and outfielder Cy Seymour, and gave them new NL homes either with himself in Cincinnati or with McGraw in New York. The Orioles, meanwhile, went from a mediocre team to a terrible one to, briefly, no team at all. On the heels of Brush’s deceitful housecleaning, the Orioles were so short of players on July 17 that they could not field a team against St. Louis; they had no option but to forfeit the game.

Witnessing the movements of McGraw and Brush as a serious attempt to undermine the AL, Ban Johnson stripped Brush of his Baltimore ownership and ran the Orioles the rest of the year on league funds, generated by the other seven clubs. The Orioles, 28-34 at the time of McGraw’s departure, limped the rest of the way by winning only 22 of their remaining 76 games, finishing in the AL cellar.

The race for the NL pennant was long decided before McGraw came on board in New York. For the second straight year, the Pittsburgh Pirates captured first place, but this time did it with juggernaut-style precision. No other team could touch the Pirates; after a 30-5 start, they only mildly settled down and never received even the slightest threat from anyone else, finishing at 103-36—a staggering 27.5 games ahead of second-place Brooklyn. Of the seven other NL clubs, the Cubs had the best head-to-head record against Pittsburgh—at 7-13.

BTW: No modern major league team outside of the 1902 Pirates won a pennant by as many games before the advent of divisional play in 1969.

Part of the Pirates’ success lay in the fact that they were, once again, relatively spared of the crippling AL player raids. Their five regular starting pitchers were all returnees from 1901; they also retained hitting standouts Tommy Leach, Fred Clarke and Ginger Beaumont. Finally—and most importantly—they still had Honus Wagner.

Wagner again tore up the NL like no other, leading the league in runs scored (105), runs batted in (91), slugging percentage (.463), stolen bases (42) and doubles (30). The Pirates continued to shift him around in the field, starting him equally at shortstop, first base and the outfield—though it was readily becoming apparent that his defensive strength lay at shortstop.

That the Pirates were able to run away with the NL pennant so easily was a clear sign of the damage delivered to the other clubs by the AL’s player raids. While the Pirates remained basically untouched, those that were hit hard by the defections showed it in the standings. The Cardinals, weakened by the arrival of the Browns, went from a legitimate contender to distant sixth-place finalists. And though the Phillies did manage to get Fraser and Duggleby back from the A’s, the two hurlers didn’t look the same and sported a combined 23-30 record; the Phillies nosedived to seventh after finishing second in 1901.

New Giants manager John McGraw had created a mess in Baltimore but inherited another one in New York. He guided a team that was 23-50 when he arrived and got a relatively competitive 25-38 effort the rest of the way—but more importantly, he began to seriously retool a franchise that would become a consistent winner for decades.

The Turnstile Wars

In its first year as a major league, the American League was outdrawn by the National League—but that changed in 1902, forcing the NL to its knees for peace negotiations by season’s end. Once unity was established, the AL continued to enjoy its first decade of major league existence with a constant edge over the NL in per-game attendance.

Even in the end, the Pirates discovered they were not totally immune to the AL’s clandestine presence. Owner Barney Dreyfuss grew suspicious that back-up catcher Jack O’Connor had been acting as a spy for the AL, courting several star Pittsburgh players to jump ship. Dreyfuss released O’Connor and three of the players who were, in fact, leaning toward the AL—including starting pitchers Jack Chesbro and Jesse Tannehill. In a case of poetic justice, all four players would wind up in 1903 with the New York Highlanders—the team formerly known as the Baltimore Orioles, and the team eventually to be known as the New York Yankees. The team that would provide direct competition to McGraw’s Giants starting in 1903.

The National League was in trouble by the end of 1902. It had resolved its internal battles, but the external war against the American League was all but lost. Its attendance dipped 15% in 1902 while the AL’s gate skyrocketed by 30%. It continued to lose its star players. It continued to lose in the courts. The seniority card was about all the NL was left with, for all that was worth.

So the NL legally cried uncle and sued the AL for peace. As a result, the two leagues finally began talking in January 1903; what would be the end result of such talks, neither league knew. All they did know was that anything would be better than the irascible situation that resulted in the baseball war of the two seasons past.

Forward to 1903: The First World Series The American and National Leagues finally agree to co-exist in peace, leading to an inaugural “world’s championship” between the two pennant winners.

Forward to 1903: The First World Series The American and National Leagues finally agree to co-exist in peace, leading to an inaugural “world’s championship” between the two pennant winners.

Back to 1901: The American League Ban Johnson upgrades his minor league circuit to the big time and scores an impressive and colorful debut, thanks to aggressive player raids upon National League rosters.

Back to 1901: The American League Ban Johnson upgrades his minor league circuit to the big time and scores an impressive and colorful debut, thanks to aggressive player raids upon National League rosters.

1902 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1902 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

1902 Leaders & Honors Our list of baseball’s top 10 hitters and pitchers in both the American League and National League for the 1902 baseball season, as well as the awards and honors given to the game’s top achievers of the year.

The 1900s: Birth of the Modern Age The established National League and upstart American League battle it out, then make peace to signal in a new and lasting era.

The 1900s: Birth of the Modern Age The established National League and upstart American League battle it out, then make peace to signal in a new and lasting era.